- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Synthetic Fuels

About this book

This book, the outgrowth of a graduate course the authors taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was designed to fill an urgent need—the training of engineers in the production of synthetic fuels to replace dwindling supplies of natural ones. The authors presented synthetic fuels as a unified engineering subject, while recognizing that many of its principles are well-understood aspects of various engineering fields.

The presentation begins with a review of chemical and physical fundamentals and conversion fundamentals, and proceeds to coal gasification and gas upgrading. Subsequent chapters examine liquids and clean solids produced from coal, liquids obtained from oil shale and tar sands, biomass conversion, and environmental, economic, and related aspects of synthetic fuel use.

The text is directed toward beginning graduate students and advanced undergraduates in chemical and mechanical engineering, but should also appeal to students from other disciplines, including environmental, mining, petroleum, and industrial engineering, as well as chemistry. It also serves as a reference and guide for professionals.

The presentation begins with a review of chemical and physical fundamentals and conversion fundamentals, and proceeds to coal gasification and gas upgrading. Subsequent chapters examine liquids and clean solids produced from coal, liquids obtained from oil shale and tar sands, biomass conversion, and environmental, economic, and related aspects of synthetic fuel use.

The text is directed toward beginning graduate students and advanced undergraduates in chemical and mechanical engineering, but should also appeal to students from other disciplines, including environmental, mining, petroleum, and industrial engineering, as well as chemistry. It also serves as a reference and guide for professionals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER

ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1SYNTHETIC FUELS AND THEIR MANUFACTURE

Gaseous or liquid synthetic fuels are obtained by converting a carbonaceous material to another form. In the United States the most abundant naturally occurring materials suitable for this purpose are coal and oil shale. Tar sands are also suitable, and large deposits are located in Canada. The conversion of these raw materials is carried out to produce synthetic fuels to replace depleted, unavailable, or costly supplies of natural fuels. However, the conversion may also be undertaken to remove sulfur or nitrogen that would otherwise be burned, giving rise to undesirable air pollutants. Another reason for conversion is to increase the calorific value of the original raw fuel by removing unwanted constituents such as ash, and thereby to produce a fuel which is cheaper to transport and handle.

Biomass can also be converted to synthetic fuels and the fermentation of grain to produce alcohol is a well known example. In the United States, grain is an expensive product which is generally thought to be more useful for its food value. Wood is an abundant and accessible source of bio-energy but it is not known whether its use to produce synthetic fuels is economical. The procedures for the gasification of cellulosic materials have much in common with the conversion of coal to gas. We consider the conversion of biomass in the book, but primary emphasis is placed on the manufacture of synthetic fuels from coal, oil shale, and tar sands. Most of the conversion principles to be discussed are, however, applicable to the spectrum of carbonaceous or cellulosic materials which occur naturally, are grown, or are waste.

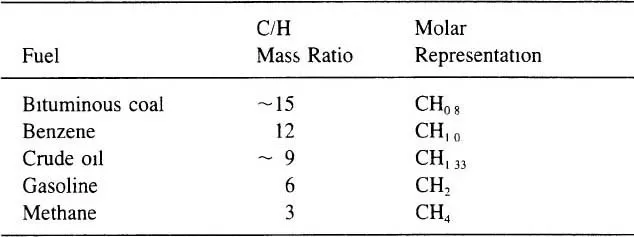

For our purposes we regard the manufacture of synthetic fuels as a process of hydrogenation, since common fuels such as gasoline and natural gas have a higher hydrogen content than the raw materials considered. The source of the hydrogen which is added is water. The mass ratio of carbon to hydrogen for a variety of fuels is shown in Table 1.1. Generally, the more hydrogen that is added to the raw material, the lower is the boiling point of the synthesized product. Also, the more hydrogen that must be added, or alternatively the more carbon which must be removed, the lower is the overall conversion efficiency in the manufacture of the synthetic fuel.

Table 1.1 Carbon-to-hydrogen ratio for various fuels

The organic material in both tar sands and in high-grade oil shale has a carbon-to-hydrogen mass ratio of about 8, which is close to that of crude oil and about half that of coal. For this reason, processing oil shale and tar sands to produce liquid fuels is considerably simpler than making liquid fuels from coal. However, the mineral content of rich tar sands in the form of sand or sandstone is about 85 mass percent, and the mineral content of high-grade oil shale, which is a fine-grained sedimentary rock, is about the same. Therefore, very large volumes of solids must be handled to recover relatively small quantities of organic matter from oil shale and tar sands. On the other hand, the mineral content of coal in the United States averages about 10 percent.

In any conversion to produce a fuel of lower carbon-to-hydrogen ratio, the hydrogenation of the raw fossil fuel may be direct, indirect, or by pyrolysis, either alone or in combination. Direct hydrogenation involves exposing the raw material to hydrogen at high pressure. Indirect hydrogenation involves reacting the raw material with steam, with the hydrogen generated within the system. In pyrolysis the carbon content is reduced by heating the raw hydrocarbon until it thermally decomposes to yield solid carbon, together with gases and liquids having higher fractions of hydrogen than the original material.

To obtain fuels that will bum cleanly, sulfur and nitrogen compounds must be removed from the gaseous, liquid, and solid products. As a result of the hydrogenation process, the sulfur and nitrogen originally present in the raw fuel are reduced to hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, respectively. Hydrogen sulfide and ammonia are present in the gas made from coal or released during the pyrolysis of oil shale and tar sands, and are also present in the gas generated in the hydrotreating of pyrolysis oils and synthetic crudes.

Synthetic fuels include low-, medium-, and high-calorific value gas; liquid fuels such as fuel oil, diesel oil, gasoline; and clean solid fuels. Consistent with SI units, we use the shorthand terms low-, medium-, and high-CV gas, where CV denotes calorific value, in place of the terms low-, medium-, and high-Btu gas which are appropriate to British units. Low-CV gas, often called producer or power gas, has a calorific value of about 3.5 to 10 million joules per cubic meter (MJ/m3). This gas is an ideal turbine fuel whose greatest utility will probably be in a gas-steam combined power cycle for the generation of electricity at the location where it is produced. Medium-CV gas is loosely defined as having a calorific value of about 10-20 MJ/m3, although the upper limit is somewhat arbitrary, with existing gasifiers yielding some-what lower values. This gas is also termed power gas or sometimes industrial gas, as well as synthesis gas. It may be used as a fuel gas, as a source of hydrogen for the direct liquefaction of coal to liquid fuels, or for the synthesis of methanol and other liquid fuels. Medium-CV gas may also be used for the production of high-CV gas, which has a calorific value in the range of about 35 to 38 MJ/m3, and is normally composed of more than 90 percent methane. Because of its high calorific value, this gas is a substitute for natural gas and is suitable for economic pipeline transport. For these reasons it is referred to as substitute natural gas (SNG) or pipeline gas. Lom and Williams1 have pointed out that originally SNG stood for synthetic natural gas, but it was observed that what was natural could not very well be synthetic.

In Figure 1.1 are shown the principal methods by which the synthetic gases can be produced from coal. Gas can be manufactured by indirect hydrogenation by reacting steam with coal either in the presence of air or oxygen. When air is used, the product gas will be diluted with nitrogen and its calorific value will be low in comparison with the gas manufactured using oxygen. The dilution of the product gas with nitrogen can be avoided by supplying the heat needed for the gasification from a hot material that has been heated with air, in a separate furnace, or in the gasifier itself before gasification. In all of the cases, the gas must be cleaned prior to using it as a fuel. This purification step involves the removal of the hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, which are products of the gasification. Medium-CV gas, consisting mainly of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, can be further upgraded by altering the carbon monoxide-to-hydrogen ratio catalytically and then, in another catalytic step, converting the resulting synthesis gas mixture to methane. A high-CV gas can be produced by direct hydrogenation, termed hydrogasification, in which hydrogen is contacted with the coal. A procedure still under development, which allows the direct production of methane, is catalytic gasification. In this method the catalyst accelerates the steam gasification of coal at relatively low temperatures and also catalyzes the upgrading and methanation reactions at the same low temperature in the same unit.

Gas can also be produced by pyrolysis, that is, by the distillation of the volatile components. Oil shale or tar sands are generally not thought of as primary raw materials for gas production, although the use of oil shale has been discussed.

Clean synthetic liquid fuels can be produced by several routes, as shown in Figures 1.2 to 1.4. For example, in indirect liquefaction (Figure 1.2), coal is first gasified and then the liquid fuel is synthesized from the gas. This procedure is not thermally efficient, relating to the fact that the carbon bonds in the coal must first be broken, as in gasification, and then in a further step some of them must be put back together again. Another procedure, illustrated in Figure 1.3, is pyrolysis, the distillation of the natural oil out of the coal, shale, or tar sands. The oil vapors are condensed, the resulting pyrolysis oil is treated with hydrogen, and the sulfur and nitrogen in it is reduced. This is similar to the procedure used in upgrading crude oil in a refinery to produce a variety of liquid fuels. Pyrolysis may also be carried out in a hydrogen atmosphere, a process termed hydropyrolysis, in order to increase the liquid and gas yield. In direct liquefaction (Figure 1.4) there are two basic procedures, hydroliquefaction and solvent extraction. In hydroliquefaction the coal is mixed with recycled coal oil and, together with hydrogen, fed to a high pressure catalytic reactor where the hydrogenation of the coal takes place. In solvent extraction, also termed “solvent refining,” the coal and the hydrogen are dissolved at high pressure in a recycled coal-derived solvent which transfers the hydrogen to the coal. After phase separation, the coal liquid is cleaned and upgraded by refinery procedures to produce liquid fuels. In solvent refining, with a low level of hydrogen transfer, a solid, relatively clean fuel termed “solvent r...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Chemical and Physical Fundamentals

- Chapter 3 Conversion Fundamentals

- Chapter 4 Gas from Coal

- Chapter 5 Gas Upgrading

- Chapter 6 Liquids and Clean Solids from Coal

- Chapter 7 Liquids from Oil Shale and Tar Sands

- Chapter 8 Biomass Conversion

- Chapter 9 Environmental Aspects

- Chapter 10 Economics and Perspective

- Appendixes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Synthetic Fuels by Ronald F. Probstein,R. Edwin Hicks, R. Edwin Hicks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.