- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

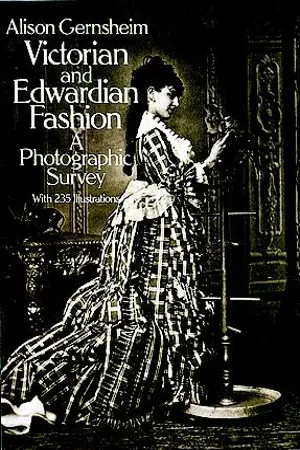

Since the invention of photography there has not been a history of fashion completely illustrated by photographs — until this one. Photography historian Alison Gernsheim first studied Victorian and Edwardian fashion in order to be able to date photographs in her collection. Of course the photos soon proved to be the best of all fashion plates — authentic, detailed, as decorative and charming as top fashion illustration. When united with identifications and descriptions of the chief costume articles, and a commentary that includes childhood memories of the period, the resulting history is doubly indispensable — equally useful and delightful to serious and casual readers.

The invention of photography preceded that of the crinoline by about a decade. Pre-crinoline bonnets, stovepipe hats, and deep décolletage are featured in the first of these 235 illustrations — including a beautiful 1840 daguerreotype portrait of a lady that is the earliest study of its kind extant. From 1855 to the 1870s the crinoline gave shape (whether barrel, bell, teapot, or otherwise) to English women, and their shapes fill many of these full and half-page photos. English men went beardless in top hats and frock coats; as in other eras, the sporting wear of the previous generation became acceptable morning and evening town attire. Styles and accoutrements came and went — moustaches, straw hats, bustles and bodice line, petticoats, corsets, shawls and falsies, flounces, ruffles, lace, and materials — satin, silk, velvet, woolen underwear, full-length sable, and osprey feathers. Many of the models for these fashions were already fashionable enough — Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Lillie Langtry, Winston Churchill, many archdukes, duchesses, counts, princes, and Queen Victoria herself. Photographers are identified where possible, and include Nadar, Lewis Carroll, and the Downeys. Every photograph is captioned and annotated.

The invention of photography preceded that of the crinoline by about a decade. Pre-crinoline bonnets, stovepipe hats, and deep décolletage are featured in the first of these 235 illustrations — including a beautiful 1840 daguerreotype portrait of a lady that is the earliest study of its kind extant. From 1855 to the 1870s the crinoline gave shape (whether barrel, bell, teapot, or otherwise) to English women, and their shapes fill many of these full and half-page photos. English men went beardless in top hats and frock coats; as in other eras, the sporting wear of the previous generation became acceptable morning and evening town attire. Styles and accoutrements came and went — moustaches, straw hats, bustles and bodice line, petticoats, corsets, shawls and falsies, flounces, ruffles, lace, and materials — satin, silk, velvet, woolen underwear, full-length sable, and osprey feathers. Many of the models for these fashions were already fashionable enough — Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Lillie Langtry, Winston Churchill, many archdukes, duchesses, counts, princes, and Queen Victoria herself. Photographers are identified where possible, and include Nadar, Lewis Carroll, and the Downeys. Every photograph is captioned and annotated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Victorian and Edwardian Fashion by Alison Gernsheim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignPART I

The Rise and Fall of the Crinoline

When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837, the trend which was later to culminate in that characteristic Victorian feminine fashion, the crinoline, had already been under way some fifteen years — ever since the narrow-skirted high-waisted Regency gowns began to give place to a waistline at natural height and skirts widening at the hem. The romantic fashions of the 1830 period with balloon sleeves, comparatively short ‘ballet dancer’s’ skirts, upstanding ‘giraffe’ hair style and flamboyant hats underwent a complete change of spirit by the time of the young Queen’s accession, as though welcoming the new bourgeois ideal.

Never before or since has Western women’s costume expressed respectability, acquiescence and dependence to such a degree as in the 1840s, the most static decade in nineteenth-century fashion. In retrospect, female costume of the ’forties seems stereotyped in form, and even contemporary fashion journalists found little new to report beyond details of trimming.

Characteristics of the period are a tight-fitting pointed bodice (1, 6, 8, 9, 12, 14, 16), and long full skirt gauged or pleated into a dome form, and supported by a small crescent-shaped bustle and innumerable petticoats. Contrary to fashion plates and descriptions, photographs belie the supposedly extremely long bodice.

Out of doors, particularly, the ubiquitous poke-bonnet and shawl or mantle produced a peculiarly respectable appearance. It is difficult to visualize the dashing lionnes of Paris society, the charming midinettes of Henri Murger, the disreputable belles of the Opera balls, and international adventuresses like Lola Montez, wearing such demure garments. Drawings by Gavarni and other caricaturists in the ’forties depict females in decidedly questionable situations, who nevertheless look like prudes.

The prevailing impression is one of severity, despite beautiful silks and dainty trimmings, and of primness even in décolletée ball dresses, for the seductiveness of the exceedingly low and wide neckline is contradicted by the stiffness of the bertha and armoured effect of the boned bodice.

In outdoor costume, women were shut in and protected. The poke-bonnet projected so far that the face could only be seen from directly in front, and the enveloping shawl or mantle made even young girls look quite middle-aged in figure. Women seemed to be trying to hide in their clothes. Feet and limbs — as the unmentionable legs were referred to — were hidden by the skirt, sleeves entirely covered the arms, hands were seldom ungloved even indoors, and the bonnet not only shielded the face but had a bavolet or curtain covering the back of the neck (No. 4, 10). People would criticize a plain, large-featured woman: ‘You can see her nose beyond her bonnet.’1

Although silks, lace, flowers, feathers and ringlets produced a charming effect, yet there was at the same time an aura of forbidden fruit. Dress was, as always, an expression of woman’s place in society.

Fashion was created in Paris — but it was the Paris of Louis-Philippe, who was laughed at for carrying a big bourgeois umbrella — in those days still a dowdy accessory. ‘Those who do not wish to be taken as belonging to the vulgar herd’, advised a Parisian snob, ‘prefer to risk a wetting rather than be looked upon as pedestrians in the street, for an umbrella is a sure sign that one possesses no carriage.’ To be sure, the Citizen King drove in a carriage, sitting between Qúeen Marie-Amélie and his sister Madame Adelaide, who bravely tried to hide him with their large bonnets, as a protection against assassination attempts, of which there were seven in his reign. Immediately after such attacks, society women would call at the Tuileries to offer the King their congratulations, wearing clothes which they kept at hand for these alarming occasions. They were known as ‘costumes for days on which the King’s life is attempted’ and were simple in form and dark in hue.2 Normally, colours were mixed in a way that sounds shocking when we read the descriptions, but it must be realized that the delicate shades of the vegetable dyes were carefully harmonized, and bright colours frowned upon as vulgar. A fashion magazine3 describes a public promenade dress of pea-green silk worn under a three-quarter-length pelisse-mantle of lavender and pink shot taffeta trimmed with Mechlin lace, and a blue taffeta redingote worn with a pink crape [sic] chapeau covered with embroidered tulle and trimmed with sprigs of roses. A pink barége carriage dress was worn with a green taffeta half-length mantle and a straw bonnet trimmed with two red and four white roses, with their foliage. Other bonnets had wreaths of grapes, cherries, and red currants. These were summer bonnets of Leghorn or rice straw, or silk. For winter, velvet or satin was the correct material, and ostrich feather tips replaced flowers or fruit as trimming.

In the 1840s all bonnets, indoor caps (Nos. 1, 6, 21), and evening headdresses came down low at the sides of the face. Bonnet brims almost met beneath the chin, and were often lined with gauged or gathered net or tulle, and trimmed with flowers inside the brim, framing the face — a pretty fashion that lasted many years. This type of ‘drawn’ bonnet was worn by Dorothy Draper when she sat to her brother Dr. John Draper of New York in summer 1840 (No. 3). It is one of the first successful daguerreotype portraits, and the earliest to survive until modern times. Miss Draper wears a pelerine or shoulder cape of transparent muslin and her dress has ‘Victoria’ sleeves with puffs on the upper arm. During that summer long tight sleeves began to come in, and were general by the autumn. These ‘Amadis’ sleeves were cut with two seams like those of a man’s coat, and were curved to the exact shape of the arm. By 1841 t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Notes on the Photographs

- Preface

- Part I: The Rise and Fall of the Crinoline

- Part II: Curves and Verticals

- Bibliography and Study List

- Index