- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting

About this book

Written by a famous American painter and teacher, whose landscapes are found in many of the world's most noted museums, this book is known as one of the art student's most helpful guides. It provides a wealth of advice on the choice of subject; it tells what to look for and aim for, and explains the mysteries of color, atmospheric conditions, and other phenomena to be found in nature.

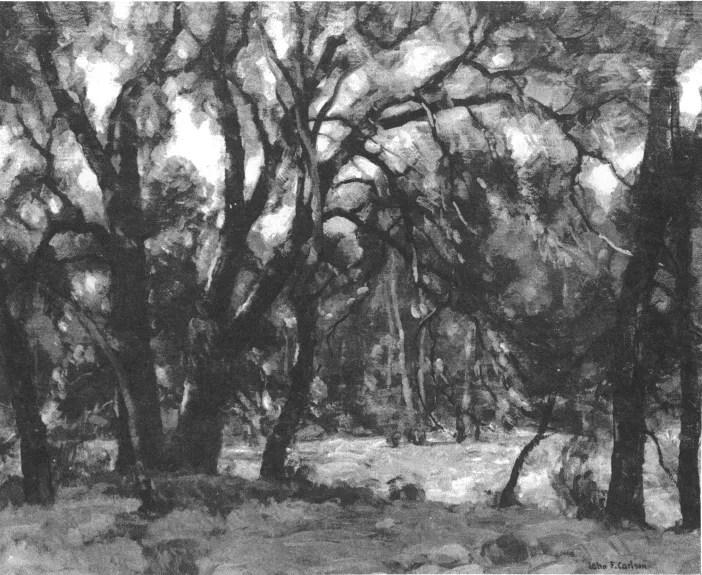

Through his profound understanding of the physical nature of landscapes and his highly developed artistic sense, John Carlson is able to explain both the whys and the hows of the various aspects of landscape painting. Among the subjects covered are angles and consequent values (an insightful concept necessary for strong overall unity of design), aerial and linear perspective, the painting of trees, the emotional properties of line and mass in composition, light, unity of tone, choice of subject, and memory work. In the beginning chapters, the author tells how to make the best of canvas, palette, colors, brushes, and other materials and gives valuable advice about texture, glazing, varnishing, bleaching, retouching, and framing. Thirty-four reproductions of Mr. Carlson's own work and 58 of his explanatory diagrams are shown on pages adjoining the text.

As Howard Simon says in the introduction: "Crammed into its pages are the thoughts and experiences of a lifetime of painting and teaching. Undoubtedly it is a good book for the beginner, but the old hand at art will appreciate its honesty and broadness of viewpoint. It confines itself to the mechanics of landscape painting but, philosophically, it roams far and wide. . . . This is a book to keep, to read at leisure, and to look into for the solution of problems as they arise, when the need for an experienced hand is felt."

Through his profound understanding of the physical nature of landscapes and his highly developed artistic sense, John Carlson is able to explain both the whys and the hows of the various aspects of landscape painting. Among the subjects covered are angles and consequent values (an insightful concept necessary for strong overall unity of design), aerial and linear perspective, the painting of trees, the emotional properties of line and mass in composition, light, unity of tone, choice of subject, and memory work. In the beginning chapters, the author tells how to make the best of canvas, palette, colors, brushes, and other materials and gives valuable advice about texture, glazing, varnishing, bleaching, retouching, and framing. Thirty-four reproductions of Mr. Carlson's own work and 58 of his explanatory diagrams are shown on pages adjoining the text.

As Howard Simon says in the introduction: "Crammed into its pages are the thoughts and experiences of a lifetime of painting and teaching. Undoubtedly it is a good book for the beginner, but the old hand at art will appreciate its honesty and broadness of viewpoint. It confines itself to the mechanics of landscape painting but, philosophically, it roams far and wide. . . . This is a book to keep, to read at leisure, and to look into for the solution of problems as they arise, when the need for an experienced hand is felt."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting by John F. Carlson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. HOW TO APPROACH PAINTING

A lifetime of painting and of teaching has convinced me that there is a general misconception as to what art study really is. Many believe that when they are reading a scientific treatise on some department of painting, or on its history or appreciation, they are “studying art.” What they are doing is studying the chronological sequences of the great painters’ lives (which is excellent for the intended lecturer), or else studying a writer’s report of his emotional responses to great paintings.

The art of painting, properly speaking, cannot be taught, and therefore cannot be learned. Only certain means can be discussed. I believe about art, as I believe about music or architecture, that the only way to study is to practice; and that any good teacher can point out certain intellectual or technical “makings,” certain helps that will give a fulcrum to the lever of practice.

Consider how little any eulogy, or even any aesthetic treatise, will help the student who first sets up his easel out-of-doors and faces nature, with its changing, fleeting panorama of color, light, movement, sound. How shall he even begin to begin? Out of his pocket bulges a volume: “The Influence of Art Upon Society.” Or another: “Does Art Uplift?” Little good will either book perform!

In this book, on the contrary, the endeavor is to present to the student of landscape painting (as well as to the lover of pictures) a few of the logical and therefore teachable aids that must underlie even the most “amateurish” approach toward achievement in this art, or toward an appreciation of the technical difficulties involved in its creation.

No one can teach “art.” No one can give a singer a glorious voice, but granting the voice, and emotional sensibility, a teacher can teach a man to sing. In painting, as in singing, there is no excuse for a poor technical performance. We take it for granted that the man who is to give a concert at Carnegie Hall knows how to sing. If he does not, we do not wish to listen to him.

In painting we are apt to be very forgiving of poor technical performance. “Why, see! See what the man intended here!” In art, intentions have no place; only results. In good art, the results do not have to be “explained.” As a matter of fact, there is but one kind of art and that is good art. There is no comfortable halfway station; it is either fine, or it is not art.

But art is a thing so much of the imagination, of the soul, that it is difficult to descend to the fundamentals of technique and yet make it plain to the student that these are but the means, and not an end in themselves. The underlying principles, or fundamentals, should be so hidden away by the beauty that they are eventually to support, that it would require much digging to disclose them. These are things we painters knew long ago, and have half forgotten. It is this that causes many teachers to attempt the impossible: that is, to start the student from the place where they, themselves, have arrived!

In this book I have proceeded upon the assumption that my readers have had little or no study, and, beginning with the bare canvas, have tried to isolate and enlarge upon the different “departments” of landscape painting until the student should have a fair idea of an approach to his task. I have tried to place these departments in useful sequence (according to their importance), taking a chapter for each. I have attempted to create a “block” or angle theory to help the student simplify, and I have tried to give the reasons for such simplification.

It is the purpose of this book to present to the student certain common sense ideas of procedure, without stifling the enthusiasm that is to carry him on. I want him to realize clearly that these ideas or rules are only beginnings; they are means and I want to warn him against considering them ends. I believe that the grave error committed in our past methods of teaching, and the thing which has caused the present uprisings against what is termed “academic training,” lies in having concentrated too much on curriculum, and not enough upon the end, which is painting.

We have technically overequipped and overloaded the poor beginner. Sometimes pedantically efficient but sadly uninspired men have been allowed to stifle the young and have turned out craft-ridden automatons. Sometimes the teacher has never made it plain that he was not a god after all, but just a teacher, with human prejudices and idiosyncrasies. We have spent so much time preparing a student that when he was prepared, he was spent. What right has anyone to ask any human being to spend three or four valuable years in the “antique class” when three or four months would suffice? Three months of study from the “block” hand, or head, or figure, suffices to give the student a good knowledge of form as expressed in mass chiaroscuro, or light-and-dark, as well as a knowledge of proportion. Instantly then, into the life class, to experience the joy of the living, moving, colorful figure! Out-of-doors, into the fields and woods, into the kaleidoscope of color and light. By and by we can return for quiet study to the antique class, and there find that we are just beginning to see and to understand the things we used to look at and not see.

How shall we approach our task of rendering these aesthetic experiences upon canvas so that our brother man may feel them with us? How shall we see nature with a painter’s eyes, and not merely as a tourist? The word “see” does not mean, in this instance, mere visual correctness; this never in itself produces a work of art. A snapshot is a correct rendition of physical fact; sharply focused it will show the numberless grasses upon the ground; it can in fact, render these so that we can see nothing else upon the print. The actual form of the mass upon which these grasses occur, it does not suggest; nor does it convey nature’s subtle color changes or color-flow. But, most of all, the camera does not have an idea about the objects reflected upon its lens. It does not “feel” anything, and will render one thing as well as another.

This “idea,” or thrill is the unteachable part of all art. It must be intrinsic in the student. It is presupposed that anyone taking up any of the arts has this inherent sensitiveness to beauty. With this native gift, he can proceed to apply the process of reducing his material to its simplest denomination, eliminating all non-essentials, and leaving only the simplified elements with which to create and express.

By diligent practice with eye and hand (and the logical lobe of the brain), he must master the fingering of the keyboard, as it were, so that technical deficiency at least will not stand between him and expression. Once this is mastered he can very well afford to forget the fingering and proceed to play Chopin or Wagner. When one has thus arrived at the point where he can play, let him not mistake this ability or dexterity for the end or final expression. Let me reiterate, it is only the means to an end.

Let the student realize at once that there is no method or style through which he can become a fine painter. Have not a care about “putting the paint on.” Put it on any way you wish, even using the thumb, if you like, so long as you will try to do the thing I shall ask of you. You will be surprised at your own style in the course of a few months. It will be unlike anything you ever dreamed of.

Style or method in painting is like your personal handwriting; you thought little about it when you were forming your first crude letters in school. We all use the same alphabet, and one man’s letters are legible to another; and yet how vastly different in general appearance! The style of your handwriting was dictated by some latent and unconscious quality within you, and even your present style will gradually change, with the years of practice in writing, or in painting, with the ripening of character. When you sit down to write an essay or a letter it is not your penmanship that you are thinking about; it is what you are going to say that occupies your mind.

The style in painting, as in writing, is subconsciously developed. You can use “thick” paint or “thin” paint; you can “stain” your canvas according to your personal feeling about it. It is what you are going to “say” on the canvas that is all-important, and not how you are going to put on the paint or handle the thing.

Many students become expert in “dashing” things in, while they still have little or nothing to do the “dashing” with! Let us, therefore, at the very start understand that painting is not a trick of the wrist, nor does it depend upon certain kinds of brushes. “Dashing style” in painting, unless the dasher knows intensely what he wants to say, is as offensive to those who are more developed artistically, as are the vociferations and fork-gesticulations of any empty-headed dinner guest. Strange as it may seem to the student, the greatest things in the world are so devoid of technical ostentation, that were it not for the immensity and grandeur of idea in the things said (the significance and insight and the dignity of it all), they would be empty indeed.

I have often said that almost all students can paint well enough at the end of a season to produce a work of art. The work of art, however, is usually slower in forthcoming. The craft of painting can sometimes be acquired in a year or two, but that is but one of the means.

If you feel things intensely and can learn to see simply (which is not a child’s prerogative, but that of an intelligent man), a style or manner will develop that will be adequate, and it will be as “individual” and different from anyone else’s style as your personal idiosyncrasies dictate.

Your color sense, too, will improve along personal lines, and it, too, will always be distinctive and “characteristic” of you. I have never met two individuals who “saw color” identically; not only the physical construction of the eye, but the personal predilection or soul-state of each individual causes him to see differently. Copies of personalities are neither possible nor desirable in our world. All schools are full of the bugbear of “personality.” This is often prompted by the desire in the student to become distinguished from his fellows, which is laudable enough, but which cannot be achieved hastily or artificially.

Beauty of method comes of experience and similarly cannot be forced. This leads us to consider what office beauty really fills in the work of art. What beauty in a physical sense really is, no man has yet fathomed. It is like an electric current; we use it, feel it, know in a sense how to harness it, but we do not know what it is.

It has always seemed to me that a picture does not rest upon beauty alone. The beauty and the recognized elements of subject matter (with the unity of idea in which they should be represented) together signify something to us; it is difficult to say what that significance is. There is a spirit behind beauty which is its cause! Beauty, therefore, must be relevant to that cause. Perhaps it is an “association of ideas,” perhaps it involves what psychologists call the personal and the collective unconscious, perhaps it involves more mystical, even religious factors.

“Symbols,” unless used for their aesthetic expression in line, color, or mass, have no place in art. If they do not possess intrinsic value they are mere conventions: an agreement between peoples that such-and-such is to represent so-and-so. There may be instances in the decorating of some specific building in which these symbols must be employed as subject matter. In such a case, if used as expressive agents of line, color, and mass, there is no reason why they should not be employed. But they become art only in the measure that they partake of abstract expressiveness intrinsic in their line, color, etc., and not because they are a convention. In this lies the difference between legitimate and illegitimate use of symbols.

It is nature that employs the first and only true symbols, the legitimate ones, when she transports us into numerous moods in which we run the gamut of emotions from laughter to tears. She accomplishes it through form, light, color, movement, sound and scent. We require no previous promptings to “understand” these things; they run through our blood, and according to our nervous receptibility, we feel them in varying degrees of intensity.

The beginner in painting begins by copying nature in all literalness, leaving nothing out and putting nothing in; he makes it look like the place or person or thing. By and by he will learn to omit the superfluous and to grasp the essentials and arrange them into a more powerful and significant whole. And it is wonderful to know that these “essentials” will be essentials to him only (and herein lies the secret of originality). Another man will choose another group of essentials out of the same fountain of inspiration.

I wish to inculcate in the student an attitude toward landscape that I have called a “landscape sense.” It is not enough even from our beginnings that we strain to copy color and form as we find them. We may succeed in doing this in a superficial way and yet not get the true sense. By the landscape sense I mean something apart from beauty, or color relation, or form relation. I mean the “float of a cloud”—the lightness of it, the filmy, airy thing that it is. I mean the weight of the ground, its solid massive form; the roll of the hills; the growth and reach of the trees—each a graceful, personal, individual thing.

Once you gain this idea, together with the superlative necessity of obtaining an expressive arrangement or design, you are on your way towards causing your studies to become pictures. The difference between a sketch and a picture lies not, as the beginner believes, in any difference in painting or handling. The sketch is a true statement of things as you found them; the picture is an arrangement of these things as you wish them to be. In either, the handling has nothing to do with the expressiveness.

Handling has only one virtue: by a very direct application of the pigment to the canvas, a certain freshness or sparkle of color obtains. But even this freshness of color, which gives a certain unlabored look to the picture, can only come with the certainty with which we paint. This certainty of value, color transitions, and forms—the “freshness,” “boldness,” “dash” which so enthralls the beginner—is really a detriment to his work; not being backed by soundness of construction or knowledge, or true artistic intention, it is offensive to those who know, w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. How to Approach Painting

- 2. The Mechanics of Painting

- 3. Angles and Consequent Values

- 4. Design—A Pattern of Differing Values

- 5. Light—Unity of Tone and the Meeting of Edges

- 6. Aerial Perspective—Transitions in Value and Color

- 7. Linear Perspective

- 8. Color—Its Emotional Value in Painting

- 9. Trees—How to Understand Them

- 10. Clouds—How They Float

- 11. Composition—The Expressive Properties of Line and Mass

- 12. The Main Line and Theme

- 13. The Extraordinary and Bizarre

- 14. Painting from Memory

- Index