- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Known as highly mobile cattle nomads, the Wodaabe in Niger are today increasingly engaged in a transformation process towards a more diversified livelihood based primarily on agro-pastoralism and urban work migration. This book examines recent transformations in spatial patterns, notably in the context of urban migration and in processes of sedentarization in rural proto-villages. The book analyses the consequences that the recent change entails for social group formation and collective identification, and how this impacts integration into wider society amid the structures of the modern nation state.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Space, Place and Identity by Florian Köhler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Taariihi

Mobility and Group Formation in Historical Perspective

Chapter 1

The Woɗaaɓe in Niger

Structure as Historical Process

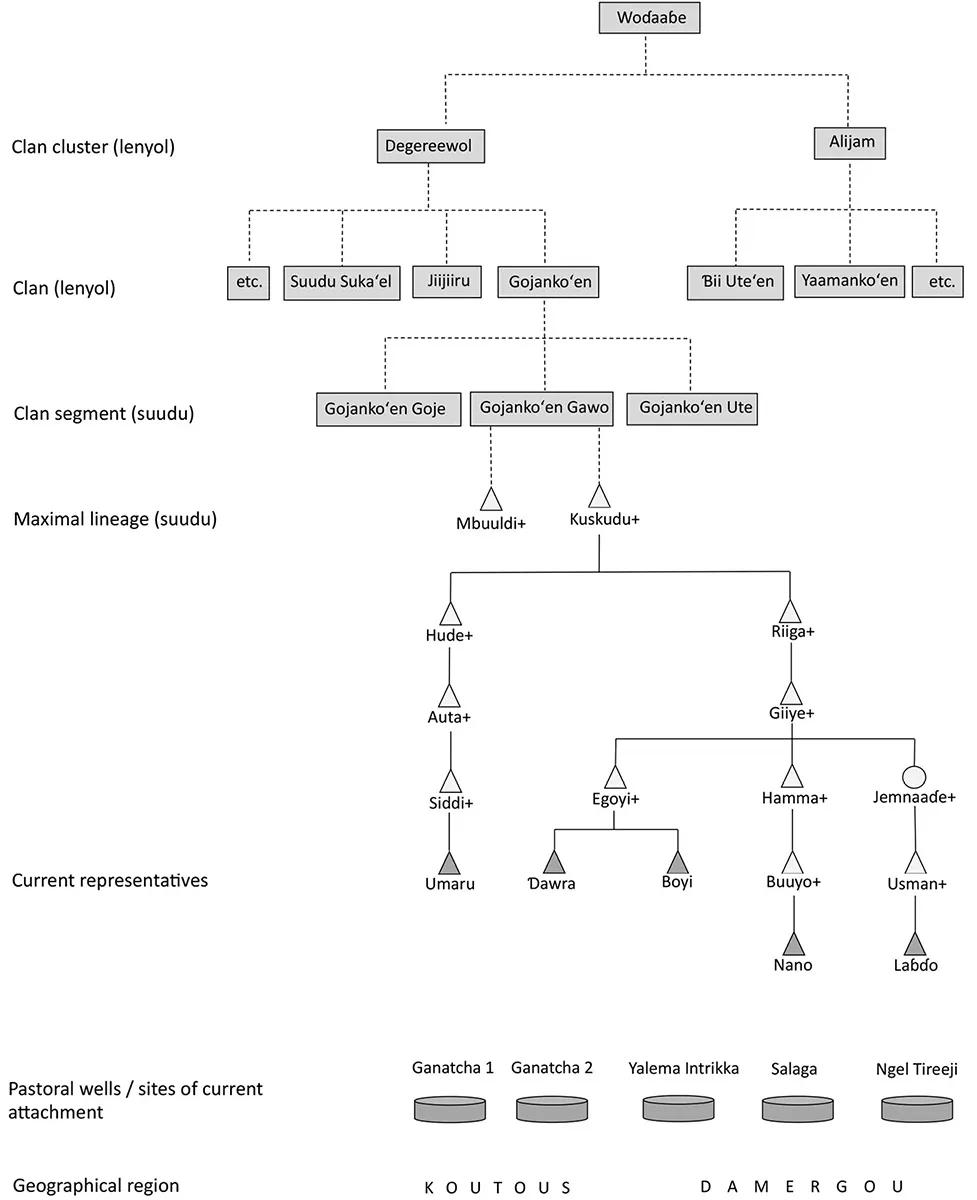

The Woɗaaɓe in Niger today comprise fifteen clans that belong to either of two opposing clan clusters, Degereewol and Alijam.1 Although research was conducted among different Woɗaaɓe communities in Niger,2 the main focus of this study was on a relatively small regional faction of a clan segment. This group is part of the Kuskudu maximal lineage, a branch of the Gawanko’en (or Gojanko’en Gawo), who are themselves a segment of the Gojanko’en clan, which is part of the Degereewol clan cluster (see Figure 1.1). More precisely, the study group has been delimited and defined as those members of the Kuskudu maximal lineage who live today in the Damergou and the Koutous regions, both situated in the Zinder province of east-central Niger.

Their migration into the region was preceded by increasingly difficult climatic conditions towards the end of the 1960s, culminating in the catastrophic drought seasons of 1973–4. At that time, larger numbers of Gojanko’en (and other groups of Woɗaaɓe) migrated to the Damergou from the Ader and Agadez regions, but a vast majority of them returned later, when conditions became better again. Only relatively few, roughly numbering 100 households, remained in the Zinder province and live there today in the Damergou and Koutous regions, engaged in a process of partial sedentarization around 5 pastoral wells that individuals have acquired or for which they have obtained management rights (see Figure 1.1 and Chapter 5). Those Gojanko’en who stayed all belong to the Gawanko’en clan segment, among them one leader of the Mbuuldi lineage, Arɗo Kiiro, with his followers (around 40 households), and a number of households of the Kuskudu lineage, which are the main object of my study and which I will discuss in more detail later. Kuskudu and Mbuuldi are the names of the founding ancestors of two maximal lineages that together constitute the Gojanko’en Gawo, or Gawanko’en. The two are said to have been brothers, Mbuuldi being the senior one. Most elders can trace their lines of descent four generations back to these ancestors.3 Figure 1.1 shows the genealogical relations of some of the key figures of this study with the lineage founder, Kuskudu.4 In order better to understand the position of the study group in the framework of the Woɗaaɓe clan structure, it seems helpful to have a closer look at how this structure has formed historically.

Figure 1.1 Woɗaaɓe clan structure, current leaders within the study group and sites of attachment (diagram by F. Köhler).

Woɗaaɓe society is composed of complementary segments of different orders, and has thus often been identified as a segmentary lineage society (e.g. Loftsdóttir 2001c; Boesen 2008a). Dupire was rather reluctant to apply this label. Although she roughly qualified the Woɗaaɓe as a lineage society (1970, 1975), she argued that one would hesitate to recognize the existence of lineages, were it not for the Woɗaaɓe’s own presentation of a system that so neatly matched with the classic scheme (Dupire 1970: 303). In practice, the Woɗaaɓe lineage system is only to a limited degree segmentary. In principle, solidarity between equal segments when it comes to defending common interests against external actors is recognizable even at the inter-clan level, as Schareika’s (2007, 2010a) analysis of political decision-making processes has demonstrated. However, the geographical dispersal of the segments of the same level and their lack of territorial attachment sets clear limits to the functionality of the principle (Dupire 1975: 337). Neither the clan clusters nor the clans ever act as corporate groups due to their fragmentation into regional factions.5

Dupire (1975: 322f.) argued that the Woɗaaɓe lineage model is not merely a construction of anthropologists, but used by actors themselves as a framework for explaining their social structure – which is not unusual for segmentary lineage societies either (Holy 1996: 80f.). Even Evans-Pritchard (1940: 143) claimed that the logic of segmentary opposition between lineages was a ‘folk-model’ held by the Nuer themselves.6 In the case of the Woɗaaɓe as in classic segmentary lineage societies, the lineage model is an ideological and ideal model of society rather than an operational model for political action (Holy 1996: 85; Salzman 1978). Schareika has correctly objected that groups among the Woɗaaɓe do not simply form naturally according to the logics of Evans-Pritchard’s classic model: the interaction of individuals and the social ties that bind them together are not merely the result of their being part of an autonomously existing lineage (2007: 163). Rather, the segmentary patrilineage constitutes a normative framework of rules and values that influence people’s orientations and offer a reference for their interpretations and judgements of social relations and appropriate interactional behaviour. In practice, individuals may manipulate the model according to their needs and interests (ibid.: 164), and other factors come into play as well. There are diverging lines of solidarity that interfere with those imposed by the logic of the lineage system. The seemingly fundamental dichotomy of the two opposing clan clusters, especially, plays a relatively minor role in daily practice. Other relations of solidarity, which can transcend the division of the clan clusters, are of greater importance for social practice. For example, some clans are closely allied for different historic reasons, often across clan clusters (Paris 1997: 77).

While the emic interpretation of group relations is that of a (relatively) coherent structure of patrilateral descent between segments of all levels, historical data collected by Dupire, and later Bonfiglioli (1988), have shown that the postulated genealogic relations between segments are in many cases rather artificially constructed. At least since Sahlins’ Islands of History, it is an established position in anthropology that social structure is not a monolithic fact, but a result of historical production (1985: vii). The clan structure of the Woɗaaɓe is a case in point, and it is noteworthy that not only is the structure here pragmatically adapted to the facts, but historic facts are also adapted to fit into a once established structural scheme. The present structure of clans and clan-clusters is the result of a complex combination of processes of segmentation of patrilineal descent groups and simultaneous counter-processes of constant re-affiliation and fusion of groups – a pattern characteristic of the Fulɓe in general (Dupire 1970; Riesman 1974; Lombard 1981), and even more generally of many pastoralist societies (Fabietti and Salzmann 1996).

On the one hand, Fulɓe communities show a tendency of splitting apart at an early stage of complexity. Ecological factors play a determinant role here: the scarcity of resources in the arid climates of the main region of distribution of the Fulɓe demands a more or less pronounced degree of mobility and does not permit a too great concentration of herds and households (Dupire 1970: 85; Lombard 1981: 188). Equally significant are economic factors linked to pastoralism. From a certain herd size, to split up the herd and the social group can be strategically advantageous (Schareika 2007: 118). Finally, sociological factors favouring individualism also contribute to the segmentation of patrilineages, in particular the system of pre-mortem inheritance that allows young men to establish independent households quite early (Riesman 1974: 45; Dupire 1970: 94; Lombard 1981: 187f.).

On the other hand, local proximity and co-residence of migratory groups often leads to alliances on the basis of common pastoral interests. Such clusters of local groups that have fused on the basis of economic and political considerations can over time develop a common identity that, through marital exchange, finally materializes in real kinship-relations and becomes rationalized ex post in the assumption of a coherent, but putative, genealogical structure (Dupire 1962: 319ff.; 1970: 296, 303f; 1975; Bonte 1979: 216; Bonfiglioli 1988: 107; Maliki 1988: 23). Dupire (1962: 320) convincingly argues that what matters is not the presence or absence of actual genetic relations, but the perception of a cultural homogeneity that manifests itself in the affirmation of a common origin. The manipulation of genealogies can thus be regarded as a means of integration of heterogeneous groups (Bonte 1979: 222; Holy 1996: 82).

Fusions between Fulɓe clans of Woɗaaɓe and non-Woɗaaɓe origin are well-documented. Particularly during the nineteenth century, due to the societal transformations brought about by the Jihad of Usman Dan Fodio and the formation of the Sokoto empire, significant cultural reorientations took place within Fulɓe society at an accelerated pace (Bonfiglioli 1988: 63, see also Chapter 4). Entire clans or lineages split away from the Woɗaaɓe and affiliated with other Fulɓe groups, and groups of other Fulɓe sections assimilated to the Woɗaaɓe and were over time incorporated along the above-outlined pattern. Against this background, the Woɗaaɓe of Niger must be regarded as a cluster of Fulɓe lineages and clans of heterogeneous origin that have regrouped in the present form and over time forged a common identity. These historic processes of group reconfiguration are apt also to explain why in different regional contexts clan patronyms can be found in different, sometimes contrarious affiliations. For instance, according to Reed, in Borno there were two distinct groups of Jaɓto’en (Njapto’en), one belonging to the Woɗaaɓe, the other to the Fulɓe Waila, both claiming not to have anything in common but their names (1932: 423, 443ff.; see also Dupire 1994: 266f.).

As for the two clan clusters (Degereewol and Alijam), their alleged genealogical relation seems no less a historic construct than those between their constituting clans (Dupire 1962: 306f.; 1972: 27). This becomes evident from a look at Stenning’s work on the Woɗaaɓe of Borno. Here, the Alijam appear not as an overarching category, but – just as the Degereeji (Degereewol) – as a clan among others, more precisely as a section of the Ɓii’Eggirga’en clan of the Woɗaaɓe (1959: 196).7 Obviously, the agnatic relations between clans claiming a common origin were no less putative in Borno than they are today in Niger. In the words of Stenning, ‘the Woɗaaɓe overcame the defects of memory by treating as agnatic the relationship of groups in the same cluster, and employing fictions to do so’ (1959: 54).

From such information one can conclude that the Alijam and Degereewol existed as clans before the formation of the contemporary Woɗaaɓe clan structure in Niger (Dupire 1962: 306; Loncke 2015: 126). It can be assumed that under the umbrella of each of the two clans that were to give their names to the contemporary clan clusters, a number of clans or lineages united and developed a common identity (Dupire 1972: 27).

Due to their pronounced mobility over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century, the Woɗaaɓe are today dispersed over a wide region across different nation states. It is therefore difficult to speak of ‘the Woɗaaɓe’ or even ‘the Woɗaaɓe of Niger’ as a clearly delimited group. Dupire (1975: 323f.) has aptly described the Woɗaaɓe of Niger as a rather loose entity with fluid limits. In the same vein, Stenning has called the ‘tribe’ a ‘vague cultural entity’ (1957: 58). The ethnic group as an entity remains hypothetical, a merely ‘imagined community’ (Anderson 1991). It has neither a single representative nor any level of interaction that coordinates all of its constitutive segments. Above the level of the primary lineage, or rather its regional segments, ‘society’ does not have any concrete manifestation apart from the periodical meetings in the course of ngaanka inter-clan ceremonies, which primarily serve to reconfirm a bond and an understanding of unity, which, however, generally concerns only the regional clan segments involved.

Following Reed (1932), Dupire (1962) considered the Woɗaaɓe of eastern Niger as distinct from the groups of the Ader and Damergou regions. Reed had maintained that although they comprised groups carrying the same clan patronyms as some Woɗaaɓe clans in Central Niger, they did not recognize any kinship relationships with those groups (1932: 425). For the contemporary groups of Woɗaaɓe in eastern and east-central Niger this cannot globally be confirmed. Although, owing to geographical distance, ceremonial relations between these groups are not maintained, the sense of historic connectedness is in some cases strong and contacts with lineage members across regions are sometimes maintained. Notably, interlocutors from a group of Ɓii Ute’en from the Manga region in eastern Niger confirmed that they are still in good contact with their relatives in the Damergou region whom they left behind upon their migration in the 1970s.8 The same consciousness of being part of a widely dispersed group was expressed by Njapto’en from the Tchintabaraden area, a faction of whose lineage once moved to Chad and live there today, even though they have not remained in contact.9 Similarly, a Gojanko’en interlocutor from the Koutous region made reference to a clan faction that moved to Chad around 1980, where they now live in an area south-east of Ndjamena (Köhler 2017a: text 3,10). A consciousness of one’s own kinship group being dispersed across different areas is pronounced, and the sentiment of being related often remains strong.

Arguably, the degree of connectedness depends on the historical distance of the separation. Unfortunately, Reed does not give any hints as to the period of separation of the groups that he mentions. With regard to the study group, as I will discuss in Chapter 2, it is striking that numerous Kuskudu of the Damergou region today entertain vivid contacts with their former home range in the Agadez region, from which they migrated around 1970, whereas their contacts with lineage members in the region of Tahoua, from which their fathers had first migrated to the Agadez region around 1940, are much lesser. The sense of historic relatedness, however, remains undiminished.

The Woɗaaɓe can probably best be considered, much like the Fulɓe of whom they are part, as a continuum with fluid limits, both spatially and in terms of group boundaries. In the course of their history, the high degree of mobility has led to a great dispersal of the Woɗaaɓe and to hybrid forms which have developed by close contact with neighbouring groups and through integration of other Fulɓe groups into Woɗaaɓe society. In such a setting, the ethnic group can probably best be defined as the largest unit of social and ritual interaction among clans or their regional segments that share an understanding of being part of a wider whole.

The pronounced spatial mobility of the Woɗaaɓe in the process of pastoral migrations makes them a highly dynamic case in terms of social group formation and reconfiguration and ultimately, identity formation. Historically, ethnic group boundaries have always been in a constant process of renegotiation, characterized by a high permeability and fluidity. The close link between mechanisms of group formation and migration means that social and spatial processes have to be regarded in close association.

Woɗaaɓe, as with other pastoral Fulɓe, live in small scattered groups. These groups, however, are not isolated units, like the islands of an archipelago, but are rather closely and multiply interconnected, and they have a strong consciousness of their connectedness over time and space. Co-residence in a loose mobile unit defines the basic social group, but for the functioning of community and society on a larger scale, translocal social relations and networks play a crucial role. In the following chapter, I will demonstrate, through the example of the study group’s mig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Language and Transcriptions

- Introduction

- Part I. Taariihi: Mobility and Group Formation in Historical Perspective

- Part II. Duuniyaaru: Spaces of Social Interaction

- Part III. Ladde: Transformations in the Pastoral Realm

- Part IV. Si’ire: Appropriating the City

- Part V. Gassungol Woɗaaɓe: The Translocal Network of the Ethnic Group

- Conclusion

- References

- Index