![]()

THE ORGAN.

________

PART I.

A SHORT SKETCH OF THE HISTORY OF THE ORGAN.

Ancient Flutes.

The history of the organ is nothing more than a narrative of the efforts made by men to bring under the control of one performer a large number of the instruments called flutes.

The particular sort of pipe or flute the use of which led eventually to the construction of an organ, was the flûte à bee or beak-flute; that is to say, a pipe with a mouthpiece which was placed against the lips for the purpose of receiving the breath of the player.

A penny whistle (tin or wood) is probably a very familiar instrument to our readers, and is a veritable specimen of a flute a bee. The now almost obsolete flageolet is also of the same family.

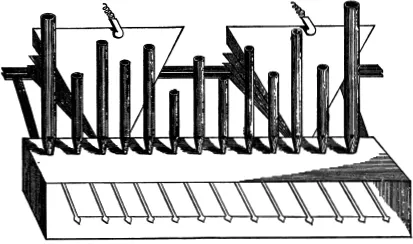

How little difference there is between a penny whistle and an organ-pipe can be seen by the accompanying illustrations:

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

When a flute was so constructed that it was blown at a hole in the side, like our modern orchestral instrument or ordinary flute, it was termed a flauto traverso or “flute held sideways.” (Fig. 3.)

Fig. 3.

It would, of course, not be possible for a performer to play more than one flauto traverso at a time; all the efforts of musicians were therefore concentrated on bringing several flûtes à bee under control.

It was very soon found that two such instruments could easily be played by one person. This seems to have been known to almost all ancient nations. The figure below is from an Egyptian monument.

Fig. 4.

The old-fashioned “double flageolet” is a real ancient “double flute” although the tubes are, for convenience’ sake, brought closer together than was the case in the older instruments. The pretty effect of the two-part harmony of the “double flute” urged men on towards the construction of an organ.

Flutes on a Box of Wind.

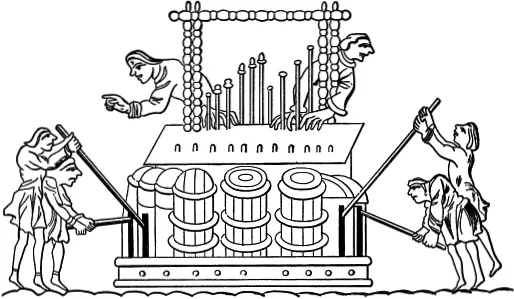

The next step in organ-building was to place several flutes on end over a box of wind, supplied not by human lungs, but by bellows. This is well illustrated by a figure copied from Kircher’s “Musurgia.”

Fig. 5.

The pipes in the above instrument (Fig. 5) were made to speak or be silent at the will of the player, by pulling backwards or forwards pieces of wood, the ends of which either closed up the foot of a pipe or allowed the wind to enter it.

As the number of pipes increased, the number of blowers necessarily became larger. The following illustration from a Saxon Psalter exhibits this :

Fig. 6.

Bellows in those times were of very primitive form, in fact not in any way superior to a common blacksmith’s bellows as used to this day in the forge.

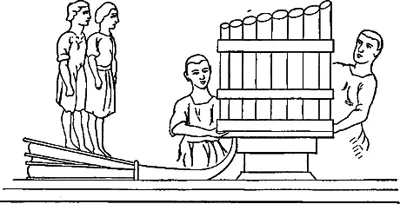

Men soon discovered that the weight of the body might with advantage relieve the muscles of the arm of the laborious duty of constant pumping. They constructed bellows of such form that men could stand on them. The following was found on the Theodosian Obelisk at Constantinople:

Fig. 7.

Hence, the blower was often called the “bellows-treader” (Balgentreter). This system of blowing has lasted up to the present time, and those who have any curiosity on this subject will still find in many continental churches, in some dark corner, a man busily engaged in mounting on first one and then another of several sets of feeders, and forcing the air into the bellows by his weight, as if he were undergoing punishment at a musical treadmill.

Reed- and Flute-Pipes.

The flutes hitherto spoken of have been those in which the tone is produced by forcing air against a sharp edge of wood or metal called the “lip,” and by this means setting the column of air inside into vibration. But the word flute or pipe anciently included a pipe of very different construction, namely, a reed-pipe—that is, a pipe in which a tongue of metal or wood is so placed that, as air is blown into the tube, the tongue, partly barring its passage, beats backwards and forwards, and by its vibration sets the column of air inside the tube into synchronous vibration. The examination of an oboe or bassoon will make the action of a reed quite clear. Thus it has come to pass that to this day these two classes of “flutes” or pipes are found in organs ; those corresponding to the common whistle family being called flue- pipes, while those of the oboe type are called reed- pipes.

Keys for the Hands.

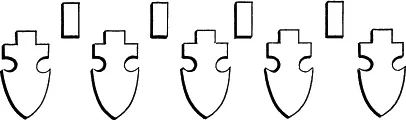

The next step in organ-making was the invention of the clavier or keyboard, about the close of the eleventh century. At first keys were of the most clumsy description (Fig. 8), so large and broad that nothing short of a blow from the clenched fist could act upon the leverage. Hence in these early times the player was called an organ-beater (pulsator organorum). It is recorded that the interval of a fifth occupied about the same space as an octave in our modern instruments.

Fig. 8.

Then little by little the keys were improved in shape until they became much like our modern keys, the only difference between them being that the old sets were much shorter (from back to front), and the sharp keys were white and the natural keys were black, the reverse of our modern colors.

Keys for the Feet.

The invention of pedals or keys for the feet, early in the fifteenth century, was probably the most important step ever made in organ-building. It is unnecessary to say here how grand and thrilling is the effect of the tone of those enormous pipes thus placed under the command of the performer, or how the independent use of the pedals gives the organist a source of harmony not possessed by any other instrument.

Pedal-keys seem to have been quickly brought to a considerable degree of perfection in Germany, where their compass soon reached or even exceeded two octaves. But in England the introduction of pedal-boards of full compass was extremely tardy; indeed, it may be said not to have commenced until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Sliders.

When only one row of pipes was placed over the box of wind the mechanism of an organ was simple enough, because each key pulled down a sort of pallet or piece of wood covered with leather placed under the foot of each pipe. As long as the key was held down the air rushed through the hole into the pipe and made it speak, but as soon as the key was allowed to return to its position the pallet returned by means of a spring to its place below the pipe and shut off the supply of wind.

But it was discovered that if a thin slip of wood be placed (running from right to left) under the row of pipes, having perforations corresponding to the holes in which the pipes stand, the whole row of pipes could be made silent by shifting this sliding piece of wood either to the right or left so far that the perforations no longer corresponded with the holes in which the pipes stood. Even when the keys are pressed down, no sound will be produced until this sliding slip, or slider, is moved into such a position that its perforations are exactly under the feet of the pipes.

These sliders are now acted upon by levers called stops, and it is by their means that several rows of pipes of different qualities of tone, and also of different pitch, can be placed over the same box of wind and yet be selected at will by the performer.

Two or More Rows of Keys.

The admirable capabilities of the organ for supporting vocal music, and the solemn dignity of its character, have always led to its association with divine worship. But the broad and strong qualities of tone found useful for sustaining the voices of a large congregation were not found delicate enough for the accompaniment of a highly trained choir either when singing individually or in a body. Hence the construction of an independent organ of soft and delicate tone called the Choir Organ, the keys of which were placed either immediately above or below the louder organ, to which latter was given the name of Great Organ. The keys of the Choir Organ are more often below those of the Great Organ than above, and the pipes of the former are often, especially in cathedrals, placed on brackets projecting over the screen behind the player’s back. In such cases the mechanism connecting the keys with the pallets and pipes had to pass below the organist’s feet, under the pedal keys, and it was called in German a Rückpositiv.

Two sorts of small organs had been in public and private use, namely, the Portatif or “portable organ,” so called because it could be carried about in processions, and the Positif or “organ in position,” so named in contradistinction, under the impression that it was not portable.

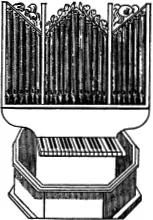

Fig. 9.

Portatif Organ.

Fig. 10.

Portatif Organ.

Fig. 11.

Positif Organ.

But, as a matter of fact, these positifs or “organs in position” were sufficiently portable to be moved from place to place with comparative ease, although they were really larger than the portatifs.

Organ-builders found in these soft sweet-toned positifs an excellent model for the organ required for choir accompaniment. Hence Choir Organs were not only built with the same sort of tone and of much the same dimensions as positifs, but were actually called positifs a name which they bear to this day in France and Germany.

The “Echo Organ” was a small organ, often of limited compass, the pipes of which were shut up in a box and placed at a distance from the rest of the instrument. Echo Organs are sometimes made now. In most instruments their place is taken by the “Swell.” The gradual alteration of an “Echo” into a “Swell” organ was, like many other vast improvements in organ-building, due to English workers. Abraham Jordan, in the year 1712, made the front of an echo-organ box to move up and down in grooves at the side like a windowsash. The-mechanism for raising the front board or shutter was of a very unwieldly character, and the pedal which set it in motion offer...