- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Album of Maya Architecture

About this book

Magnificent guide presents 36 sites from Central America and southern Mexico as they appeared more than a thousand years ago: Temple of the Cross, Palenque; Acropolis and Maya sweat bath, Piedras Negras; Red House and north terrace at Chichén Itzá; more. Each illustration features text of archeological finds and line drawing of remains. 95 illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Album of Maya Architecture by Tatiana Proskouriakoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

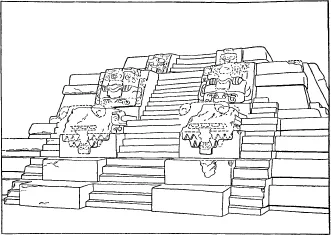

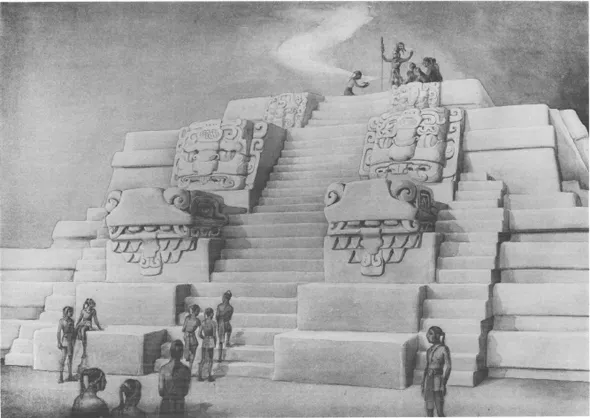

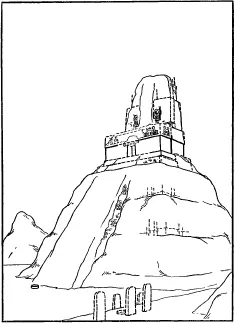

UAXACTUN, GUATEMALA

Structure E-VII sub

A COMPLETE description of this structure and its excavation may be found in UAXACTUN, GUATEMALA, GROUP E—1926-1931 (1937) by O. G. and E. B. Ricketson.

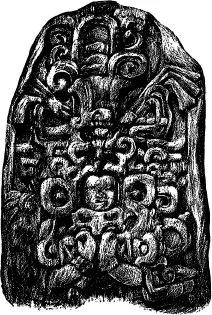

The motif below is Stela 20 of Uaxactun.

UAXACTUN

Structure E-VII sub

UAXACTUN, in the heart of the Maya Old Empire, is buried in the dense, tropical forests of northeastern Peten. It is only one of many sites in this region which contains greater and more spectacular ruins, but it is of particular interest to the archaeologist because among its monuments are the earliest stelae yet discovered in the Maya area, as well as one of the latest. The Carnegie Institution began excavations at Uaxactun in 1926, and the hope that a city of such long occupation would yield examples of early architecture was amply rewarded when a trench through the badly ruined Pyramid E-VII uncovered a huge stucco face, almost perfectly preserved under later masonry. Further digging revealed that this was one of eighteen grotesque heads that decorate the stairways of the small pyramid now known as E-VII sub. Associated pottery finds indicate that this pyramid is very old—older, in fact, than the earliest stelae. It was probably intended to support a temple constructed of wood and thatch, for in the upper platform there were originally four deep post holes, which were later filled and smoothed over with plaster, as if the building had been razed, and its substructure adapted for outdoor ceremonies.

The pyramid is roughly square, with stairways on all four sides, but the upper platform has only one stairway and is higher at the rear than at the front, resembling in form the building platforms of later temples, built entirely of masonry. A striking feature of the construction is the irregularity of its shape: its grossly inaccurate angles and proportions. The facing stone is very roughly cut, laid horizontally, and covered with a thick coat of plaster. The whole looks less like a masonry structure than like a form carelessly modeled from some more plastic substance or cast in a rough mold. In spite of the crudity of workmanship, however, its well-defined design and the use of decorative elements which remain characteristic of Maya art throughout its entire history, clearly imply an established architectural tradition, and one which awaited only increased technological skill to reach full flower.

There is rude vigor in the execution of the two motifs of its ornament. One, in spite of its battered condition, can tentatively be identified as a simplified version of the serpent. The other is anthropomorphic, though to call it man or deity is perhaps to tempt biased interpretation. It is better described noncommittally as a mask, the favorite motif of decoration in all subsequent Maya styles. The significance of masks is obscure, and in their variations they exhibit a gamut of human and animal features which is difficult to unravel. Even if in time we discover a meaning in their complicated attributes, we can never be sure that this meaning was intended by the artist. It is quite conceivable that, with constant repetition, formerly significant designs become merely abstract elements of composition, and many grotesqueries may be the result of an arbitrary mixture of traits from widely different sources. If the masks did possess a purposeful significance, we must seek even earlier examples than those of E-VII sub to discover whether this already conventional form once had a more naturalistic prototype that would permit us to give it a name.

2

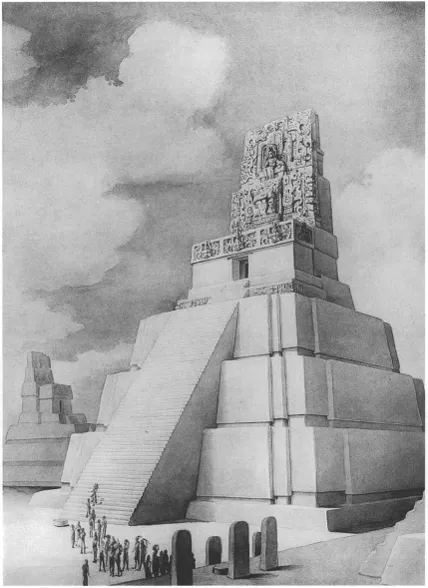

TIKAL, GUATEMALA

Temple II

A PLAN and section, photographs, and a description are published in EXPLORATIONS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PETEN, GUATEMALA (1911-1913) by Teobert Maler. The restoration is based partly on this report and partly on unpublished measurements and notes taken at the site by E. M. Shook in 1941.

The head of the Maya priest is restored from fragments of carved wooden beams found in Temple II.

TIKAL

Temple II

TIKAL is one of the largest and one of the least accessible of ancient Maya cities. Its massive temples tower above the forest that envelops and conceals countless lesser buildings, still unexplored. For many decades archaeologists have dreamed of the exciting possibilities offered by the excavation of this spectacular city, a task that would require years of effort even by a large and well-equipped expedition. The lack of a dependable source of water supply near Tikal is one of the many obstacles that have prevented intensive exploration even of the surface remains, and, although many have visited the site, few have stayed there long enough to take adequate measurements and notes of the buildings. Detailed and reliable information is scanty. This restoration of Temple II is presented with great hesitation, for it is based on insufficient and conflicting data. It is included in this series only because other examples of its type are even less well documented, and because it represents the crowning development of the temple in Old Empire times, and the composition of its mass alone may serve to illustrate the effect which the Maya builders aimed to attain. In 1941 Mr. Edwin M. Shook, of the Carnegie Institution, visited the site and obtained accurate measurements of the building itself, the platform on which it is built, and the standing portions of the roof comb. Except for the stucco decoration, which is largely destroyed, the restoration of these features is probably substantially correct. The form of the terraces of the pyramid, however, is very uncertain, as well as the exact slope of the steep stairway, which can be seen now only as a ruined mass of stone. Mr. Shook’s work at Tikal was hampered by unseasonable rains, and the short period of his stay prevented his taking more than very cursory notes on the details of the substructure. These notes disagree both with the drawings presented by Maler and with the model constructed under the supervision of Dr. Herbert J. Spinden, in the Museum of Natural History in New York. In some respects, Mr. Shook’s notes find confirmation in photographs, but one important feature, the existence of a low plinth or projecting molding at the bottom of each terrace wall, remains in question.

Of the five great temples at Tikal, Temple II is the smallest. The largest, Temple IV, is more than two hundred and twenty-five feet in over-all height, and is sketched on the accompanying map of the Maya area to emphasize the massive composition of Peten architecture in contrast to that of adjacent regions. The actual room space of these temples is very small in comparison with the thickness of masonry which surrounds them, and their vaults are very high and steep. A number of lintels that spanned the doorways are still preserved. They are made of the hard, heavy wood of the sapote tree and some are beautifully decorated in the formal, ornate, but sensitively naturalistic style of the greatest period of Maya art. If we accept the chronological evidence of these lintels, which, however, may have been carved years after the erection of the buildings, we must conclude that the religious architecture of Tikal remained extremely conservative. Experiments in vault construction and variations of plan were impeded by the weight of the ponderous roof combs, and interior space was sacrificed to the effect of height and grandeur. No doubt the religious cult of the time presented to the populace an august spectacle, but reserved its secret rites and sciences for the privileged few who were instructed in its mysteries. The forbidding temples seem to express the exalted aloofness of the priesthood that ruled this great city.

3

PALENQUE, CHIAPAS

Shrine in the Temple of the Cross

SECTIONS and plans of the Temple of the Cross are published in BIOLOGIA CENTRALI-AMERICANA, Archaeology (1889-1902) by A. P. Maudslay. The combined section and perspective shown by W. H. Holmes in his ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES AMONG THE ANCIENT CITIES OF MEXICO disagrees in some details with the Maudslay drawings.

The sculptured plaque is from Palace House E.

PALENQUE

Temple of the Cross

UNLIKE the ponderous temples of Tikal, those of Palenque reflect a taste which aspires to perfect proportion rather than to an overwhelming effect of sheer mass. The pyramids are not so high as to dwarf the buildings they support. Doorways are wider and more frequent, rooms are wider and vaults lower, and the roof combs, perforated to reduce their weight, are not so remotely aloft that their exquisite stucco sculpture could not conveniently be observed and enj...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- UAXACTUN, GUATEMALA

- Back Cover