eBook - ePub

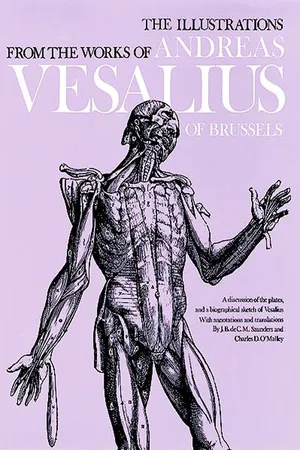

The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels

About this book

The works of Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) have long been regarded among the great treasures of the Renaissance. Published as medical books while he was teaching anatomy and dissection at the University of Padua, they include the Tabulae Sex (1538), intended as an aid to students; the magnificently illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), and the companion volume, the Epitome (1543). Individually, these books are milestones in the history of medicine. They also offer one of the most magnificent collections of anatomical drawings ever published. The plates were executed with such vitality and originality that they have been attributed to the most talented illustrators of the sixteenth century, not to mention Vesalius himself. Many of the drawings, in fact, were products of Titian's famous atelier.

For this edition of the Vesalius illustrations, Dover has combined the best existing plates and text. The illustrations have been reproduced from the sumptuous (1934) Munich edition of Vesalius titled Icones Anatomicae. The Munich plates were struck for the most part from the original wood blocks then in the collection of the Library of the University of Munich. These priceless art objects were destroyed in the bombing of Munich during World War II. Aside from the original copies of the woodcuts (of which only a few complete sets are known), the Munich restrikes are the best representations of the Vesalian anatomical drawings, for they preserve much of the freshness and richness of the 1543 edition.

The text of this Dover edition has been faithfully reproduced from an edition of Vesalius published by World Publishing Company in 1950. The editors, distinguished authorities on sixteenth-century medicine, have provided a very comprehensive history of Vesalius, his career, and excellent explanations of the legends surrounding the illustrators, artists, and publishers involved with the production of his books. No other source will provide the general reader, bibliophile, art historian, artist, or historian of science and medicine with such complete data on Vesalius and his fabulous anatomical illustrations.

For this edition of the Vesalius illustrations, Dover has combined the best existing plates and text. The illustrations have been reproduced from the sumptuous (1934) Munich edition of Vesalius titled Icones Anatomicae. The Munich plates were struck for the most part from the original wood blocks then in the collection of the Library of the University of Munich. These priceless art objects were destroyed in the bombing of Munich during World War II. Aside from the original copies of the woodcuts (of which only a few complete sets are known), the Munich restrikes are the best representations of the Vesalian anatomical drawings, for they preserve much of the freshness and richness of the 1543 edition.

The text of this Dover edition has been faithfully reproduced from an edition of Vesalius published by World Publishing Company in 1950. The editors, distinguished authorities on sixteenth-century medicine, have provided a very comprehensive history of Vesalius, his career, and excellent explanations of the legends surrounding the illustrators, artists, and publishers involved with the production of his books. No other source will provide the general reader, bibliophile, art historian, artist, or historian of science and medicine with such complete data on Vesalius and his fabulous anatomical illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels by J. B. Saunders, J. B. Saunders,Charles O'Malley,Charles O’Malley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art TechniquesTHE PLATES

FROM

THE FIRST BOOK

OF THE

DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA

FROM

THE FIRST BOOK

OF THE

DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA

NOTE: The illustrations on the plates are described from left to right and thence downward row by row. This is indicated in the enumeration with each descriptive text. The first figure indicates the plate and the second the position of the individual figure on the plate. The numbers in brackets refer to the book and chapter in the FABRICA where the proper context may be found.

All text in italics is translated directly from the Latin of Vesalius. All text not in italics is by the translators.

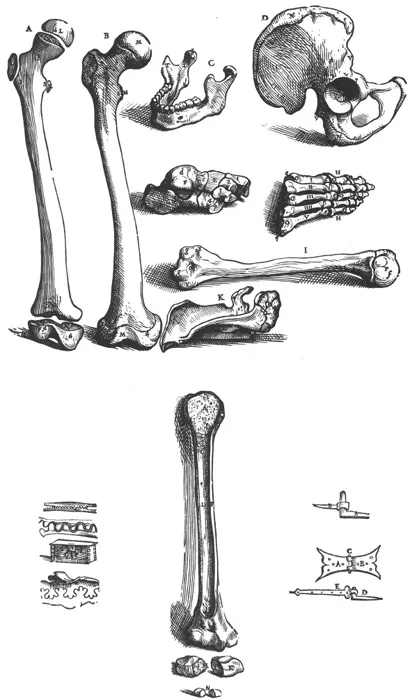

Plate 4

4:1 [I:iii]. The attached figure delineates several of the bones for the sole purpose of representing, at least in some of them, the bony parts and regions, the names of which I shall consider in this Chapter.

In the chapter illustrated by these figures, Vesalius discusses the various technical terms employed in osteology such as an epiphysis, apophysis, process, spine, head, neck, shaft, articular surface, etc. The skeleton selected as a model for the earlier plates of the Tabulae Sex (q.v.) was that of a young man, aged eighteen, who obviously suffered from rickets; but for the Fabrica the bones from a more perfect subject, of approximately the same age, were obtained; hence the epiphyses or lines of epiphyseal fusion are frequently observed as in this plate. The ossification of the acromion process, as here indicated, was somewhat anomalous since it is stated that there were several distinct centers. Other points of interest are that the term “tarsus” designated the three cuneiforms and the cuboid only, and that the metatarsus, like the metacarpus, consisted of four elements since, following Galen, the first was regarded as a phalanx.

Preliminary sketches in red chalk of some of the figures of this illustration are to be found in the Glasgow Codex and have been attributed to van Kalkar. These have been reproduced by Ludwig Choulant in his History and Bibliography of Anatomic Illustration (Chicago, 1920).

4:2 [I:iv]. The four small figures here shown were inset in the chapter to point analogies in the discussion of the cranial sutures. They demonstrate successively a serrate joint, a joint ad unguem or by interdigitation, dovetailing and hemstitching by means of “florettes.”

4:3 [I:i]. As the different bones represented by figures attached to each chapter in which the individual bones are described, are shown intact, so that the remaining matters considered in the present chapter are not demonstrated, we have depicted here a portion of the humerus dissected longitudinally....

Below the humerus, sectioned longitudinally, Vesalius has placed the navicular bone of the foot and the first phalanx of the great toe, both divided in half. His purpose was to demonstrate cancellous bone, the medullary canal and the compact cortex. In addition, Vesalius included the smaller bones in order to confute Galen’s opinion that these were solid.

4:4 [I:iv; xv, 1st ed.]. Here the letter A indicates the metal or hinge implanted in the wall; B, the metal joined to the door or window.

A small figure inset in the chapter to illustrate comparisons which may be drawn between a hinge and a ginglymus joint.

4:5 [I:iv, 2nd ed.]. The upper figure represents a hinge, as described in the text, by which two boards are joined; A indicates one metal element and B the other, while C is the key which makes firm the mutual ingression of the former. The lower figure delineates another type of hinge in which D denotes the metal fixed to the wall and E the metal by which the key is attached to a door or window.

An elaboration for the second edition of the Fabrica of the previous figure and again employed to illustrate the description in the text of the nature of a ginglymus joint.

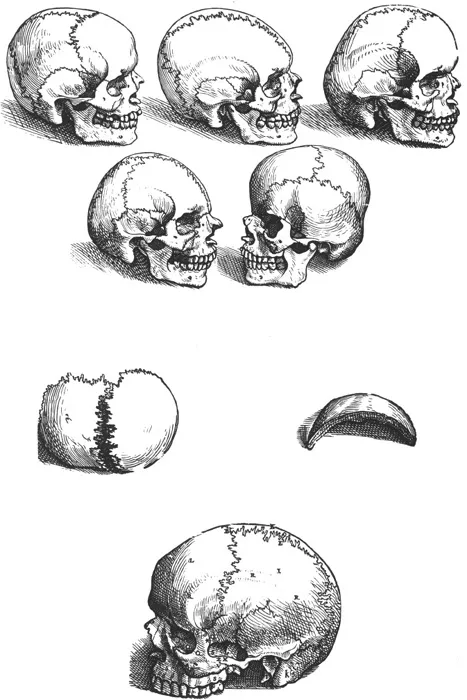

Plate 5

5:1 [I:v]. In the first figure is delineated the natural head or skull shape which resembles an oblong sphere slightly depressed on either side and protruding anteriorly and posteriorly.

5:2 [I:v]. The second figure demonstrates the first type of non-natural [abnormal] head shape in which the anterior eminence is lost.

5:3 [I:v]. The third shows the second type of non-natural head shape in which the anterior [error for “posterior”] eminence disappears.

5:4 [I:v]. In the fourth is indicated the third type of non-natural head shape in which both tubers, that is, anterior and posterior, are lost.

5:5 [I:v]. In the fifth we represent the fourth type of non-natural head shape in which both the eminences of the natural shape face, not to the front and rear, but to either side.

These are the first meager beginnings in physical anthropology. Although conscious of racial differences, Vesalius attempted to establish a norm for skull shape of which the four abnormal types were variants. He further believed that the pattern of suturation was related to the prominence or lack of prominence of the cranial eminences; hence in his abnormal type I the coronal suture is absent, and the sagittal continues as the metopic to the nasal region, and the reverse in type II, an inter-occipital suture being represented. He was, however, aware that suturation varied with age. These beginnings had their inspiration from the works of Hippocrates, and such criticism of the Vesalian classification as developed was at first based upon opinions as to whether he had correctly interpreted the classical authors.

5:6 [I:vi]. The first figure of the sixth Chapter which shows the two portions of the bones of the vertex [parietals] somewhat separated so that the very skillful construction of the suture may be seen more conveniently.

5:7 [I:vi]. The second figure of the sixth Chapter displays a portion of the bone of the vertex [parietal] divided by a saw from the rest of the bone so that the substance of the skull in the forehead, vertex and occiput is exposed, which is formed by two dense and solid squames or laminae, commonly called the tables and the diploe....

5:8 [I:vi]. The third figure of the sixth Chapter exhibiting the whole skull without the lower jaw, depicted on the left side.

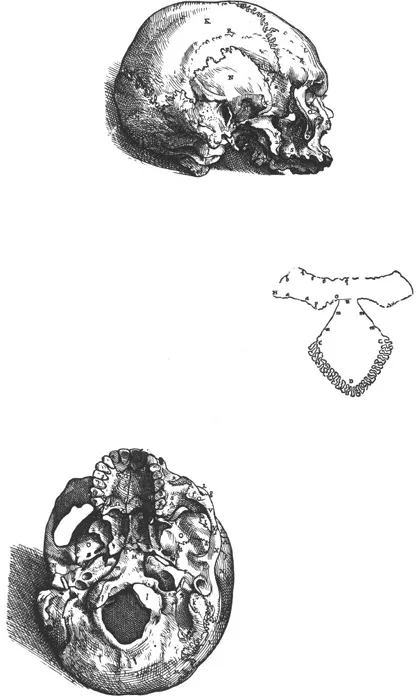

Plate 6

6:1 [I:vi]. The fourth figure of the sixth Chapter represents the skull lying further on the left side so that the base of the skull comes somewhat into view. In this figure we have removed the jugal [zygomatic] bone with a saw to expose several of the sutures....

6:2 [I:vi]. A schematic diagram inserted in the index to the figure on the base of the skull seen below. It represents the sutural boundaries of the occipital bone and of the greater wings of the sphenoid. The denticulate portion from D to C is the parieto-occipital suture, followed by the occpito-temporal suture at m and the junction of the basi-occiput with the basi-sphenoid at n. Thereafter the boundaries of the greater wing of the sphenoid and its articulation with the temporal, parietal, frontal, zygomatic, maxillary and palatine bones are indicated at appropriate intervals by letters.

6:3 [I:vi, ix]. The base of the skull is shown; anteromedial to the foramen spinosum in the scaphoid fossa between the pterygoid laminae on the right side of the illustration may be seen the inconstant “foramen of Vesalius,” one of the few structures which is eponymously named for this great anatomist.

Plate 7

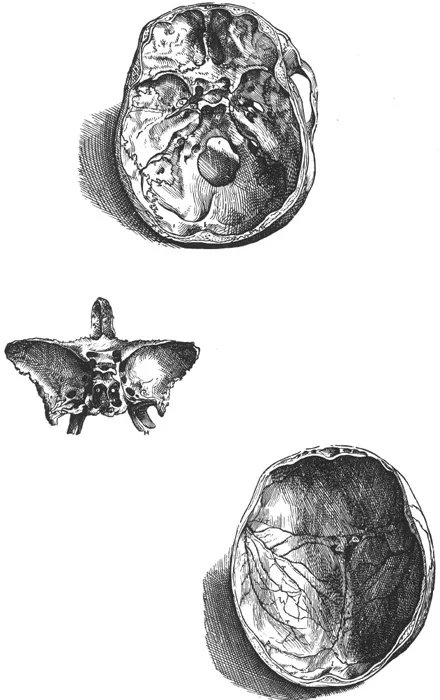

7:1 [I:vi, xii]. The sixth figure of the sixth Chapter exposing to view the internal aspect of the base of the skull. We have here delineated the skull from which the superior part, represented in a subsequent figure, has been removed in the manner in which we customarily divide the head with a saw when we are going to show the structure of the brain.

The foramen of Vesalius is now seen on the left of the illustration, just lateral to the anterior clinoid process and anterior to the foramen spinosum marked by the letter Q (cf. Fig. 6:3). Such correspondences would indicate that the same skull was used in the majority of the illustrations.

7:2 [I:vi]. As I do not wish in the least to annoy the reader with numerous plates, I am, for that reason, purposely not representing in the above the individual bones of the head by separate figures. However, because the boundaries of the wedge-like bone [sphenoid] and of the eighth bone of the head [cribriform plate of ethmoid] are not so readily understood as the rest, in the present figure these bones freed from all others are represented from that aspect which faces the internal surface of the skull. We have displayed the cuneiform [sphenoid] so that the hollows frequently occurring in it might be shown....

By tilting the sphenoid somewhat its sinuses and the foramina passing forward to the orbit are revealed for the first time in the series. The ethmoid of Vesalius is the cribriform plate and processes only, since difficulties in the preparation of such a delicate bone led him to believe that the ethmoid labyrinth was a separate bone which he called the “spongiform.” Gabriel Fallopius later corrected the error by employing the skulls of infants and children to obtain the bone intact.

7:3 [I:vi, xii]. The seventh figure of the sixth Chapter showing the remaining portion of the internal aspect of the skull, not represented in the sixth figure.

The calvaria from the skull in the previous illustration is now exposed to exhibit not only the markings of the meningeal vessels but also the internal appearances of the suture lines and such details as the fossae for the arachnoidal granulations associated with the name of Antoine Pacchioni (1665-1726), an anatomist and physician of Rome and Tivoli.

Plate 8

8:1 [I:ix, xii]. This figure represents the anterior aspect of the skull in which the bones of the upper jaw are shown as accurately as possible. We have placed the skull of a dog beneath that of man so that anyone may understand Galen’s description of the bones of the upper jaw without the slightest difficulty. In addition, it was necessary to rest the human skull on its occiput and to set its anterior portion on the dog’s so that the orbits with the sutures and bones appearing in them may be more clearly seen....

This arresting illustration was of extraordinary symbolic significance to Vesalius, who employed it twice as a chapter heading. Apart from its obvious value for the demonstration of the boundaries of the facial bones, the primary purpose of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Introduction

- Plates. The Title Pages of the Primary Editions of the De Humani Corporis Fabrica

- Letter to Johannes Oporinus

- The Plates from the De Humani Corporis Fabrica

- The Plates from the Epitome of the De Humani Corporis Fabrica

- The Venesection Letter of 1539, PLATE

- The Plates from the Tabulae Sex

- Plates showing evolution of the title page of the first edition of the De Humani Corporis Fabrica