- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drawing What the Eye Sees

About this book

Heralded as a revolutionary right-brain approach to figure drawing, this guide focuses on mentality rather than technique. Ted Seth Jacobs offers personal reflections and advice on developing the ability to draw what the eye sees rather than what the mind dictates. More than 180 black-and-white drawings and eight pages of color illustrations reinforce his insights into such concepts as light, balance, and symmetry.

Jacobs' mental approaches include drawing as a philosophical expression, encouraging the mind and body to work together, and cultivating a relaxed but attentive mood. His observations on figure drawing range from the portrayal of forms in action and at rest to draped effects; and he explores the nature of shadow, reflected light, and other light-related issues. Above all, he encourages readers to challenge all assumptions about drawing and painting. A valuable teaching tool for students, this volume is also an excellent reference for professionals and amateurs.

Jacobs' mental approaches include drawing as a philosophical expression, encouraging the mind and body to work together, and cultivating a relaxed but attentive mood. His observations on figure drawing range from the portrayal of forms in action and at rest to draped effects; and he explores the nature of shadow, reflected light, and other light-related issues. Above all, he encourages readers to challenge all assumptions about drawing and painting. A valuable teaching tool for students, this volume is also an excellent reference for professionals and amateurs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drawing What the Eye Sees by Ted Seth Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art Techniques1

Thoughts

About

Drawing

About

Drawing

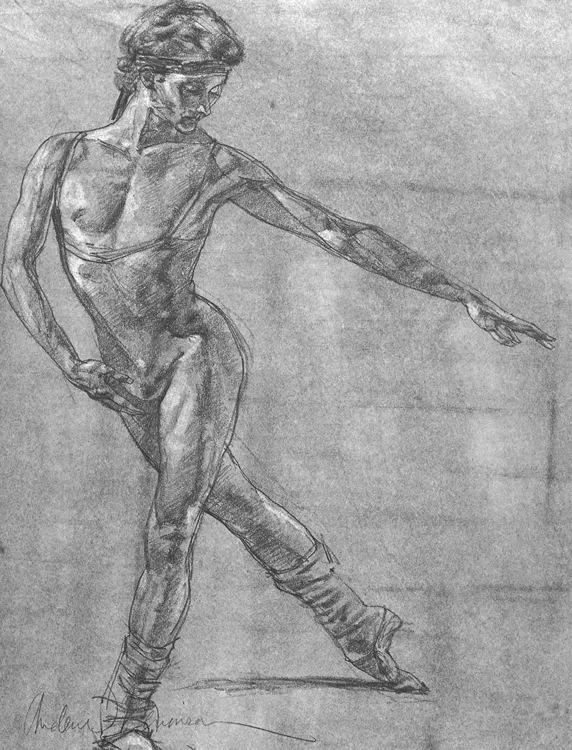

ANDREW LEVINSON

Sepia Conté chalk and pastel on paper. 20″ × 14″ (50.8 × 35.5 cm). 1982.

This drawing, and most of the other dance drawings presented in this book, are taken from the artist’s 1981 one-man exhibition “The World of Dance” at Coe Kerr Galleries, New York.

What is drawing? At first glance the question seems simple enough to be superfluous; but upon reflection it becomes not only difficult, but perhaps not even definable.

Suppose an answer is given as, “Marks on a surface, representing something.” Although the first part of that answer doesn’t seem to present any problems, the second part does. Do marks need to represent something in order to be qualified as drawing? Even if within the term “something” can be included the broadest inferences—such as an idea, a representation of something seen, a mood—it can be argued that the marks need not represent anything, that in their graphism, independent of all association, they constitute drawing. If that definition is accepted, how can drawing be differentiated from any other form of marking? As an extreme instance, can we say that footprints are or are not a form of drawing? I recall seeing an Indian dancer who put a staining agent on the soles of her feet, and during the course of her dance upon a stretched cloth, produced a stylized drawing of a peacock. If that is drawing done by a dance, are footprints a drawing done at a walk? The problem is that any definition seems either too exclusive or inclusive. The term “drawing” possibly cannot be defined. If it is indeed impossible to define terms, I wonder whether it is necessary to do so. What compels us to define? Is it habit, an approach to thought that urges us to define something before discussing it? If define we must, ought we, on the basis of all the ideas that arise around the subject, allow a definition to suggest itself? But without a definition, how can we know the subject of our speculations, out of which we hope to realize a definition?

These questions may sound sophomoric, but they in fact infest the roots of our thought processes, the relationship between thought and language, and, as I hope will become apparent, the deepest reaches of the process of drawing.

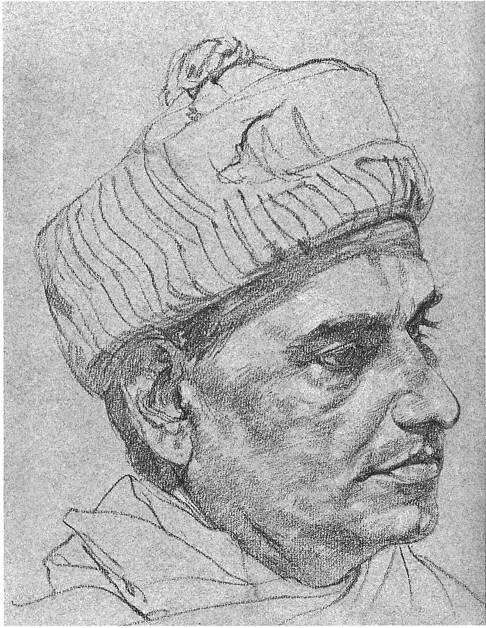

ANTUBHAI VEDYA, AYURVEDIC DOCTOR

Sanguine chalk on gray paper. 10″ × 8″ (25.4 × 20.3 cm). 1953.

When you draw from life, it’s easy to forget that what you’re making is a drawing rather than a recreation of a person on paper.

Among the many things it may be, drawing is a trace, a track, a trail—like the leak from an oil-line down a highway or the progress of the worm in the woodwork, the print, the fossilized remains of movement. Even the fish in the ocean, the free bird in the sky, draw an invisible arabesque after themselves. In this sense, drawing is the relic of movement.

Movement, it may be said, is the translation of intent into action. On the origins of intent and desire I will not presume, but surely desire is a cry from the deepest corners of our being. This way of considering drawing creates a linked progression through time. From urge to idea to movement to trace, or drawing. This suggests that everything stands for something anterior and other. But is it just as possible that the drawn stroke is the original urge? Then perhaps everything only, stands for itself. In this context, it is even conceivable that drawing may be the free-standing original impulse that subsequently generates conceptions which then pique to life the sleeping snake of desire. And for those of you who are not passionate partisans of logical systemics, drawing may be all of these coexisting simultaneously. But however much of all these things that drawing may be, it is, as we will see, much more.

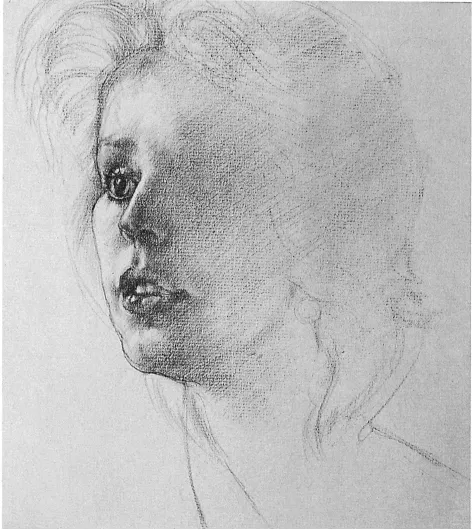

LAURIE LEVETTE

Sanguine lead on sand-colored paper. 1979.

Although it seems all to self-evident, drawing only suggests or symbolizes a perceived object; it can never recreate that object.

Drawing can suggest, represent, or symbolize perceived objects. But how in fact can this be possible? Of foremost importance when examining questions about representational drawing is the fact that the drawing is not and never can be the object it portrays. This appreciation seems so self- evident as to appear unnecessary, but it is honored by draftsmen more often in the breach than in the observance. When engaged with the difficulties of drawing from a model, the artist can easily forget that he is not indeed recreating that model on paper. It seems laughable, incredible that anyone may fail to notice that difference, but experience shows that an absorption in the drawing process can blind people to simple verities. When drawing, any form of blindness is undesirable, and this elementary lack of discrimination produces deformations in drawing.

In fact, I find it much more difficult to imagine how people came to accept line as a representation of perceived forms. It requires a stupendous leap of imagination, and an enormous extension or a gross suspension of belief! By what mechanism of intricate association can we infer any connection between the object we see and the line meant to represent it? I have read theories to the effect that drawing may have originated when early man traced the edges of his left hand as it lay flattened against the wall of his cave, or when he traced around the edges of shadows cast by fire. That may or may not be true; but I wonder what then impelled early humans to define objects against other objects by their outermost edge? One can easily imagine that the center of an object, its supposed core, or even a suggestive or striking feature, might more forcefully symbolize an entity Perhaps there is some innate drawing faculty embedded in man’s nature that accounts for this phenomenon. It is, for instance, hard to imagine that a dog could recognize his kind by an outline. Do animals recognize their own cast shadows?

The whole basis of linear representation is surprising in view of the fact, as frequently noted through the ages by artists, that lines as such do not exist—nor do contours. The outermost visible limits of one object against another are certainly not linear. The ocean’s horizon is where the sea more or less stops and the sky begins, but it is in no way a line.

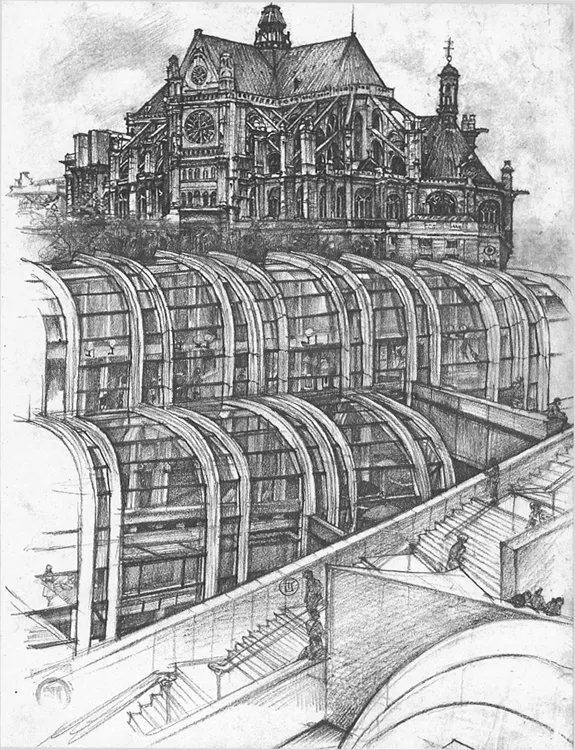

THE CATHEDRAL OF ST. EUSTAGHE AND THE FORUM, PARIS

Pastel over Conté and pencil. 14″ × 11″ (35.5 × 27.9 cm). 1980.

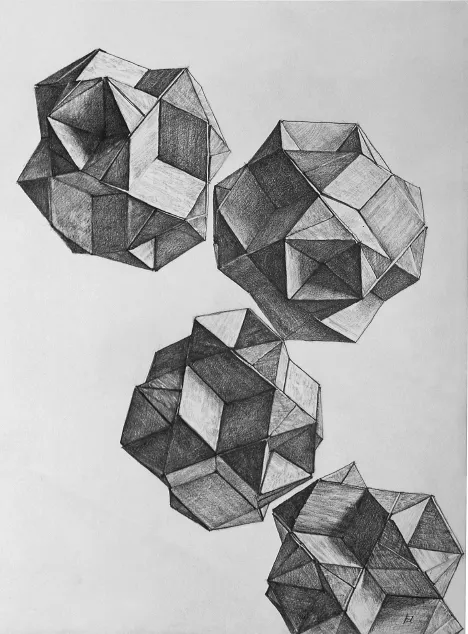

CHINESE PUZZLE

4B pencil. 12″ × 10″ (30.4 × 25.4 cm). 1985.

Lines and contours do not exist in nature.

To be precise, nothing has absolutely fixed outer limits. The objects we perceive intermingle at their edges. Besides, whatever auric emanations they emit, light is very irregularly refracted from the surfaces of forms; and all forms are very irregularly surfaced. It would require an immense technological deployment to create even a relatively unbroken outer edge between two objects. The surfaces would need to be machine-smoothed to an extreme precision, the light refracted from them at all points isometrically, and all traces of atmosphere removed from the premises. The eye of the beholder of all this would also need to be some nonhuman bionic device.

If one takes the trouble to examine the limits of seen objects, they appear more like the interreactive, intermingling edges of floating clouds of colored gases. Nothing within our field of vision exists in isolation. All is mutual interaction: reflection and counter-reflection, radiances interpenetrating.

Even beyond these considerations, it is important to remember that the act of sight is a living process. As such, it vibrates with the rhythms of our being, humming and fluttering all the time! Sight itself is certainly not rigid, fixed, or motionless; sight is motion looking at motion. Out of all this turbulent agitation, where does the wire-like rigidity of outline come from?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Thoughts About Drawing

- Thoughts About Drawing the Figure

- Thoughts About Light

- A Few Words About Technique

- In Conclusion

- Index