- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Illustrated Art of War

About this book

Graced with color illustrations of Asian art treasures, this gift edition of the world's earliest and most prestigious military treatise covers principles of strategy, tactics, maneuvers, and other ever-relevant topics. Required reading in many military institutions, its ancient wisdom offers many modern applications to business, law, and sports. "There's not a dated maxim or vague prescription in it." — Newsweek.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Illustrated Art of War by Sun Tzu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chinese Warfare

IN TIME OF PEACE, the very low pay of the Chinese soldier attracted only the peasant and laboring classes. In war a better class was attracted by higher pay and the prospect of plunder or prize money. About 170 A.D., the custom was started of raising forces from among those Tartars who had become Chinese subjects, for special service on the frontier. This was found to furnish soldiers of ability, but of doubtful loyalty.1

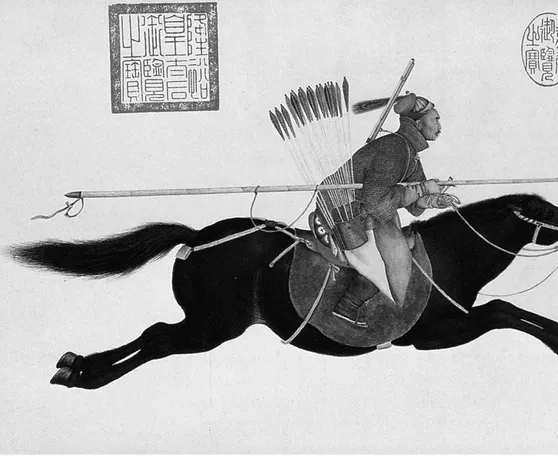

It is probable that for centuries most of the Chinese soldiers were infantry. About 117 B.C., a force of about 150,000 cavalry was raised for service against the Tartars, but this seems to have been exceptional. Every force had some bowmen and spearmen. In the early wars chariots were used.

Reform in the Army

Under the Emperor Taitsong (763–780 A.D.) there was considerable reform in the army. He organized his army of 900,000 men into 895 regiments of about 1,000 men each. Of these, 261 regiments were used for service on the border and 634 for service in the interior of the country.

The Chinese troops had no training corresponding to our drill or combat exercises. For instruction in horse-back archery, a shallow trench about a hundred yards long was dug so that the rider would not have to guide his horse. As the horse ran down the trench, the rider shot an arrow at a target twenty or thirty yards away, but seldom hit it. Other exercises, such as wrestling, throwing large stones, and use of heavy swords seem to have been intended to encourage muscular development.

Sparse mention of the staff is found in Chinese history. Supply seems to have caused more trouble than anything else. We find one emperor who himself agreed to take charge of the supply of an army of 600,000 men so as to relieve its commander from this worry. About two hundred years later generals protested that an expedition ordered by the emperor could not be undertaken because proper supply arrangements could not be made in time. They added that supply considerations limited a campaign in cold and windy regions to a maximum of one hundred days. Supplies seem to have been drawn by slow-moving oxen, and the forage for the oxen was a large item in regions where they could not be supported by grazing.

Spies Extensively Used

For information of the enemy, the Chinese depended largely on spies. In the intervals between battles, negotiations were frequently carried on, not for the purpose of settling the difficulty without fighting, but to introduce envoys into the enemy’s camp so that they could keep in touch with what was going on. Captured enemies were frequently induced by bribes, threats, or torture to disclose plans. The Chinese used advance guards, but not reconnoitering detachments.

This lack of security caused them to be taken frequently by surprise.

Five kinds of spies are listed and their use is treated in detail in The Art of War. Sun Tzu could well understand how the German aviators were able to bomb Polish headquarters every time it was moved in September, 1939.

In the Chinese armies one arrangement in command was faulty. Mandarins who had achieved distinction as civil functionaries studied military tactics late in life and directed operations in time of war, while officers of experience could not expect to reach the highest grades. As might be expected, this system frequently brought disaster to Chinese arms.

Chinese Weapons

Weapons generally used were bows and arrows, spears, war chariots, swords, daggers, shields, large iron hooks, and iron headed clubs about five feet in length and weighing twelve to fifteen pounds. The standard equipment of the Wall guards consisted of a sword, a crossbow, and a shield. The bows were of three classes according to the force necessary to bend them. Each man was issued one hundred and fifty arrows. Two kinds were used and both had bronze heads. Quivers were issued to carry the arrows.

The Chinese discovered gunpowder before 255 B.C., but used it only for fireworks until much later. Isolated instances are given of its use for military purposes, in 767 A.D. and 1232 A.D., but cannon were not used for the defense of the Wall until the Ming Dynasty in 1368 A.D., about the time they were first used in Europe.

No Medical Corps

The Chinese had very little knowledge of medical science. They had even less knowledge of anatomy, because of religious convictions against mutilation of a dead body and the drawing of blood. Hence they practiced almost no surgery. They placed great reliance on diagnosis by the pulse. They claimed that by taking the pulse at different places, they could tell the state of health of the different organs, and even determine the sex of an unborn infant. As they had no knowledge of sanitation, epidemics were frequent. The most common classes of diseases were those of the eye, skin and digestion; and intermittent fevers were common. No mention is made of a medical department in the army. The losses from disease were high in the campaigns, and the wounded had slight chances of recovery.

The Great Wall

The greatest military engineering feat of the Chinese was the construction of the Great Wall. Many historians give the Emperor Chin Hwang-ti credit for the construction of the Wall, but portions of it were in existence before he came to the throne (221 B.C.). Repairs and extensions were made as late as the eighteenth century.

The part built by Hwang-ti had a two-fold purpose: ( 1 ) to act as a barrier against the barbarians, and (2) to serve as a monument to the union of China. He had just succeeded in breaking up the feudal system and had united China under a strong central government.

Hwang-ti’s portion was built under the direction of an army engineer, General Meng Tien. His force consisted of 300,000 soldiers and hundreds of thousands of other laborers. The soldiers aided in the construction work when they were not needed to repel attacks. This portion of the Wall was completed about 204 B.C., after the death of Hwang-ti.

In later years Tartar activities caused the Wall to be extended, and new loops were built south of the original wall. In 423 A.D., a section about seven hundred miles in length was built running almost north and south along the western border of the province of Shensi. In 543 A.D., a second portion was built in Shensi, far south of the original wall. In 555 A.D., 1,800,000 men were used to build that part of the Wall near the present site of Peking. This is the wall usually seen by visitors to China.

Construction of Great Wall

The Great Wall, following all its curves, loops, and spurs, is about 2,550 miles long. The direct distance between its two ends is 1,145 miles. There were about 25,000 towers on the Wall and 15,000 detached watch-towers. The cross-section and the material used varied. At one point it was seventeen feet, six inches thick and sixteen feet high; it had two face walls of large brick, the space between being filled with earth and stones. On the Chinese side, the face wall was carried up three feet higher than the earth and stone filling, to form a parapet. On the Tartar side, the parapet was five feet high and cut down at frequent intervals with embrasures. The material used varied from solid masonry, with good stone and brickwork, down to a mere barrier of reeds and mud.

The Wall guards were organized into companies of one hundred and forty-five men under a commandant, who was responsible for a small group of watchtowers. A few mounted messengers were assigned to each company. Several companies were grouped into “sections of the barrier” under a higher officer, who reported directly to the Governor of the province.

Training was not at all complete. Troops were disbanded when they were not needed; they were called to the colors when necessary. The troops who guarded the Great Wall might better be called settlers. They were given grants of land near the Wall and encouraged to marry. The result was that when a soldier’s particular unit was not actually on guard on the Wall, he cultivated his land and had not time for training. At other times and places in the Empire, the low pay forced the soldier to seek additional employment, with the result that the Chinese army was composed of laborers and peasants who gave their spare moments, if they had any, to military exercises. The Emperor Taitsong’s army of 900,000 soldiers had less value than 300,000 real soldiers.

At intervals along the Wall piles of dry reeds were kept ready for building signal fires to give warning of the approach of the Tartars. The strength of the attacking force was given by repetition of the fire signals. It was considered a serious offense for the soldiers at a watch tower to fail to transmit a signal received. The watch stations were about two and a half miles apart. Rockets were also used for signaling.

There is no information that the Chinese had any general reserves back of the Wall, as the Romans had for their frontier defenses. The Chinese had defending troops at the gates; but between the gates the Wall served principally as an obstacle to small raiding parties, because the Tartars could not get their horses over it and small bands of barbarians without tools had difficulty in opening a passage through it. The Tartars were helpless without their horses and would not think of making a raid on foot.

The Wall did not prevent great invasions, as the Tartars in large bodies passed it many times. But such irruptions were made possible by the weakness or disloyalty of the defenders rather than by any weakness of the Wall itself. For example, when Genghis Khan ( 1162–1227) invaded China he bribed his way through a gate in the wall.

Military Transportation

In spite of the great number of boats on the canals and rivers, water transportation for military purposes seems to have been seldom used before the time of Kublai Khan ( 1216–94). About 280 A.D. a fleet on the Yang-tse-kiang was used in one of the civil wars. Again, in the year 969 A.D., an attempt was made to use boats in an expedition against the Cathayans, but low water so hindered the expedition that it failed.

The condition of the roads varied according to the character of the emperor. They were generally poor. Under the more energetic rulers, there were eras of road and bridge construction. Under poor rulers, and in periods of civil war, the roads were permitted to go to pieces. The Emperor Hwangti, who ordered the Great Wall built, constructed many roads. The Emperor Kaotsou (202–194 B.C.), founder of the Han Dynasty, used 100,000 men to construct a strategic road across the mountains to the city of Singafoo. Many suspension bridges were used on this road. The most notable was 150 yards long, wide enough for four horses to tr...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Bibliographical Note

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chinese Warfare

- ONE - Laying Plans

- TWO - Waging War

- THREE - Attack by Stratagem

- FOUR - Tactical Dispositions

- FIVE - Use of Energy

- SIX - Weak Points and Strong

- SEVEN - Maneuvering an Army

- EIGHT - Variation of Tactics

- NINE - The Army on the March

- TEN - Classification of Terrain

- ELEVEN - The Nine Situations

- TWELVE - Attack by Fire

- THIRTEEN - Use of Spies