- 108 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

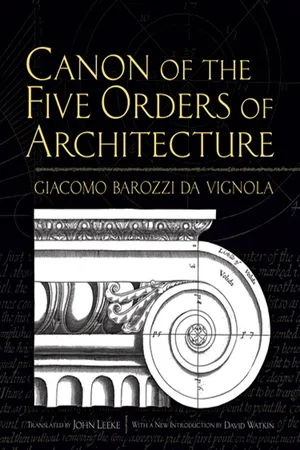

Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture

About this book

One of history's most published architectural treatises, this Renaissance volume solidified the architectural canon of the past five centuries. In these pages, the distinguished architect known as Vignola identified the five orders — Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite — and illustrated them in full-page elevational detail.

Vignola's engravings have been copied countless times since their original publication in 1562. The clear images with brief captions constitute a practical rather than theoretical work, offering even lay readers a system of tools that provide accurate proportions. An essential reference for professional architects, this book has guided generations of architects, including those who rebuilt London after the Fire of 1664. This new edition features an Introduction by architectural historian David Watkin.

Vignola's engravings have been copied countless times since their original publication in 1562. The clear images with brief captions constitute a practical rather than theoretical work, offering even lay readers a system of tools that provide accurate proportions. An essential reference for professional architects, this book has guided generations of architects, including those who rebuilt London after the Fire of 1664. This new edition features an Introduction by architectural historian David Watkin.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, John Leeke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitectureINTRODUCTION

“It is always necessary to know what we want our eyes to see.”

—Vignola, Regola 1562

The Life and Work of Vignola

Vignola, author of what has been seen as the most influential of all architectural treatises, was employed for over thirty years in the papal service, notably that of Alessandro Farnese, Pope Paul III (reigned 1534–49), and his grandsons, Alessandro (1520–89), Ottavio (1524–86), and Ranuccio Farnese (1530–65). Pope Paul III was a major architectural patron, responsible for the monumental Palazzo Farnese in Rome, and for commissioning Michelangelo to renovate and rebuild the Campidoglio. He was also a central figure in the Counter Reformation, summoning the Council of Trent in 1545, and authorising the foundation of the Society of Jesus for which Vignola was to build its mother church in Rome, the hugely influential Gesù (1568–73).

Despite attracting such powerful patrons, Vignola was himself modestly born in 1507 in the village of Vignola, hence the name he acquired. He was raised in nearby Bologna where he was trained as a painter, but turned to architecture, probably in early the 1520s under the influence of the great painter-architects, Baldassare Peruzzi (1481–1536) and Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554), both of whom were then active in Bologna. Serlio was preparing his life work, L’Architettura, a treatise codifying the five classical orders of architecture that profoundly influenced Vignola’s own Regola delli cinque ordini of 1562.

In 1538 Vignola moved with his wife and children to Rome where, working as a painter and designer, he became involved with the Accademia della Virtù.1 Led by the humanist Claudio Tolomei, this academy of antiquarians, humanists, architects, men of letters, noblemen, and clerics, formed a plan to publish a multi-volume illustrated study of Vitruvius and ancient architecture, to which Vignola contributed measured drawings, now lost. There were many such academies in Renaissance Italy to which talented young men of humble birth were admitted on equal terms with noblemen who might become their patrons. One such academy was that of Count Giangiorgio Trissino in Vicenza of which Palladio’s membership established his career. It is likely that Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, to whom Vignola was to dedicate his Regola, may have met Vignola through the Accademia del Virtù, where the Cardinal’s secretary was a member.

Vignola now went to Fontainebleau to cast bronze replicas of classical statues in the Vatican for King François Premier. Here in 1541–3 he had further contact with Serlio, but returned to Bologna where he had been appointed architect of S. Petronio by Pope Paul III in 1541. Here, he was confronted by the task of how to complete this Gothic basilica but all attempts proved abortive. An early work by Vignola, far removed from the rigid system of his later Regola, is Palazzo Bocchi, Bologna, begun in 1545 in a bizarre and Mannerist language, but not completed to his design.2 It was commissioned by a learned patron who chose the emblematic sculptural programme and inscriptions that appear on its façade.

In 1559 Vignola settled permanently in Rome, continuing in the service of the Farnese family as well as becoming architect to Pope Julius III (reigned 1550–5), a post that Vasari claimed to have obtained for him.3 For Pope Julius he built the Villa Giulia (1550–5), with Vasari and Ammanati,4 and the nearby Sant’Andrea, Via Flaminia (1550–3), with an interior featuring a revolutionary oval cornice and dome. This spatial experiment, for which nothing in his Regola prepares us, was developed more fully in his S. Anna dei Palafreniere in the Vatican (1565–76), where the whole nave was an oval, though in a rectangular shell. As the first Italian architect to build a church with an oval ground plan, he exercised a considerable influence on Baroque architecture. There is a further freedom at S. Anna in that the interior is unrelated to the exterior and the entrance façade is organised quite differently from the side façades.

Before his elevation to the papacy as Paul III in 1534, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had begun a moated, pentagonal fortress at Caprarola, north of Rome, from designs by Antonio da San Gallo and Peruzzi in the early 1520s. This gigantic powerhouse was probably only one storey high when Paul III’s grandson, Alessandro Farnese, commissioned Vignola to complete it to a totally different design of his own in 1555. He changed the central pentagonal court to the more harmonious circular form inspired by Raphael’s incomplete Villa Madama, Rome (c.1518–30). Built from 1559 to 1573, Vignola’s Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola shows his genius as an architect, engineer, urban planner, and painter, for it was conceived in scenic and symbolic terms, dramatically approached from a specially created axial road, sixteen metres long, terminating in a composition of ramps, staircases, and a drawbridge.

The astonishing circular staircase inside the Palazzo, with superimposed columns of the Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite, orders, was combined “with a wealth of balusters, niches, and other fanciful ornaments,” as Vasari put it. The Palazzo was crowned by giant cornice, a highly original blend of Doric and Corinthian over Composite pilasters, which Vignola chose to illustrate in his Regola. Vasari praised the “rich and regal villa of Caprarola,” explaining that the client’s ambition was that “the whole work should spring from the fanciful design and invention of Vignola.”5 It shows us the other side of Vignola’s aesth...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- To the Reader

- The Translators Preface

- Back Cover