- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

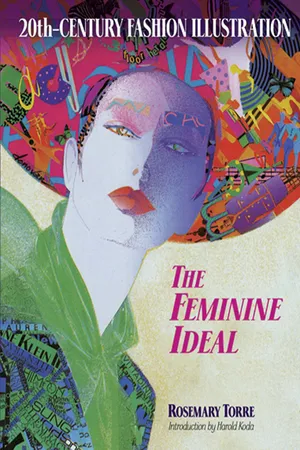

About this book

This fascinating retrospective chronicles the rise and development of modern fashion illustration from the early 1900s to the dawn of the twenty-first century. Its lively narration, illustrated by over seventy original works by fashion's top illustrators, explores the social context of fashion illustration with feminine ideals that characterize each era:

• The Temptress (1900–20) — Turn-of-the-century stage idols and screen vamps

• The Garçonne (1920s) — The emancipated post–World War I woman

• The Grown-Up and the Glamour Girl (1930s–40s) — Working girls and movie stars of the Great Depression and World War II

• The Princess (1940s–50s) — Dior's New Look and the USA's postwar cultural dominance

• Twiggies and Hippies (1960s–70s) — Protest and revolution, The Beatles, Twiggy, Warhol, psychedelics, flower children, and women's libbers

• The Jetsetter (1980s–90s) — The Me Generation, the cult of fitness and perfection, supermodels and super career women

• The Fashionista (1990s–2000s) — The massive influence of entertainers, sports figures, and the rich and famous

• The Lady or the Tiger — Summarizes the Ideal's march through the century

Professional fashion illustrator Rosemary Torre taught for three decades at New York City's Fashion Institute of Technology. Her original and authoritative survey features informative captions for each image and detailed biographies for every illustrator. Fashion-conscious women of all ages will treasure this captivating book, as will students and professional fashion and costume designers.

• The Temptress (1900–20) — Turn-of-the-century stage idols and screen vamps

• The Garçonne (1920s) — The emancipated post–World War I woman

• The Grown-Up and the Glamour Girl (1930s–40s) — Working girls and movie stars of the Great Depression and World War II

• The Princess (1940s–50s) — Dior's New Look and the USA's postwar cultural dominance

• Twiggies and Hippies (1960s–70s) — Protest and revolution, The Beatles, Twiggy, Warhol, psychedelics, flower children, and women's libbers

• The Jetsetter (1980s–90s) — The Me Generation, the cult of fitness and perfection, supermodels and super career women

• The Fashionista (1990s–2000s) — The massive influence of entertainers, sports figures, and the rich and famous

• The Lady or the Tiger — Summarizes the Ideal's march through the century

Professional fashion illustrator Rosemary Torre taught for three decades at New York City's Fashion Institute of Technology. Her original and authoritative survey features informative captions for each image and detailed biographies for every illustrator. Fashion-conscious women of all ages will treasure this captivating book, as will students and professional fashion and costume designers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 20th-Century Fashion Illustration by Rosemary Torre, Harold Koda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignThe Grown-Up

and

The Glamour Girl

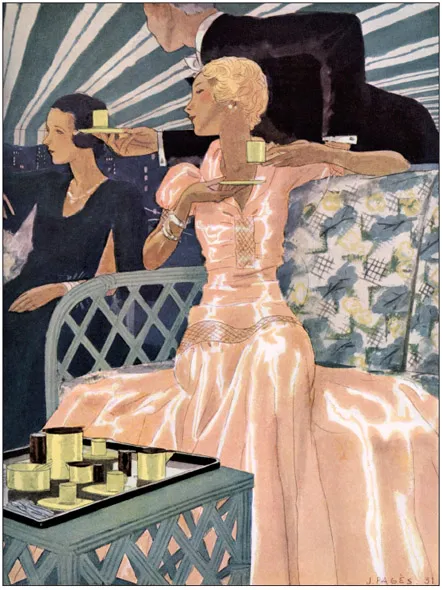

Pages, Vogue, Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast.

The Thirties Ideal seems to have relinquished cocktails for a sobering demitasse. Shimmering fabric and a close-fitting bodice play up her feminine curves. Jean Pages, a young Frenchman, joined Vogue in the late Twenties and continued to grace its issues into the Forties.

The feminine Ideal that emerged in the Thirties and Forties was the personification of grace under fire. Both decades were marked by economic, political, and social turmoil, resulting in varying degrees of deprivation and untold psychological trauma. The Great Depression of the Thirties, precipitated by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, announced in bold-faced type that the rollicking Twenties were over. The madcap Garçonne grew up and metamorphosed into a levelheaded woman, ready to face the challenges of a precarious economic condition. She continued to work if she had a job, or looked for one to augment a reduced family income. She learned to live more simply: sans servants, vacations, furs, jewels, or seasonal refurbishing of house and wardrobe. In retrospect, Chanel’s “poor look” of the Twenties—spare suits and jersey dresses—had been a harbinger of things to come: a rich look in this decade would have been in poor taste.

As always in times of stress, the Ideal woman was supportive, compassionate, and reassuring; and for these traditionally feminine roles the costume of an abbreviated cylinder would not do. In the late Twenties, designers had given women tired of the “garter gap” the choice of longer hemlines via floating panels and handkerchief hems. By the Thirties, Jean Patou had dropped the hemline to the ankles and returned the belt to the natural waistline. Longer skirts seemed to lend an air of comforting maturity. Perceptive designers such as Vionnet and Alix (Mme Grès) draped and cut fabric on the bias to create gowns that now revealed womanly physical attributes. The two-cup bra took the place of chest flatteners, and nothing was left to the imagination in a backless satin gown or a wet maillot. Hair was worn longer and softly waved, brows were plucked and arched to lend delicacy to the face, lips were given rococo curves, and a floral scent was indispensable.

The Garter Gap

Fashion magazines, a source of inexpensive entertainment, assumed an instructive role, guiding readers through the straits of the Depression, teaching them how to make do and, in spite of the sorry circumstances, exhorting them to remain “soft,” “lovely,” “romantic.” Practicality was stressed in shopping for clothes, and Bazaar counseled, “…make for black if you want to look dressy without dressing.” In addition, women’s magazines provided jobs for women as editors, writers, fashion reporters, illustrators, and photographers.

The efficient working girl was the new heroine, personified by Christopher Morley’s Kitty Foyle. She could be found at the typewriter, behind the counter at Woolworth’s, in beauty salons as manicurist or colorist, or as a model in fashion showrooms. Whatever her position, she was conscientious and reliable. She augmented her limited wardrobe with jabots and removable collars and cuffs; she lifted her spirits with a jaunty hat; and she used cosmetics as a morale booster. Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden were among those who understood the psychological benefits of an attractive appearance and who created empires in response to this basic feminine need. It was important for all levels of society to keep up appearances. In the city, the; Thirties woman would not leave home without her hat and gloves, and she dressed for dinner, perhaps by adding a pair of clip pins to her neckline or a bit of veiling to her daytime hat.

One of hundreds of black and white illustrations by anonymous artists in the Thirties. The relaxed stance is typical—flat derriere and tummy, bent knee, demeanor calm and relaxed.

The universal form of entertainment was the cinema. Like a miniature Versailles, the gilt and mirrored movie house was the residence of the reigning kings and queens of the Silver Screen, who were now heard as well as seen. Movies provided escapism and a glimpse of the spunky working girl epitomized by Jean Arthur, Rosalind Russell, and Barbara Stanwyck. She was self-sufficient, pragmatic and resilient—in a word, a Grown-up. She wore the same white-collared dress until she married the boss and ended the movie in lamé and furs. A more worldly version of the working girl was offered by Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, and Jean Harlow, who also exhibited strength and resilience. (Who can forget Dietrich following her soldier into the desert in high heels?) In superb creations by Adrian and Edith Head, they added a fillip to the current Ideal—dazzling allure. Women imitated the mannerisms and appearance of their idols—slouching like Garbo, chain-smoking like Bette Davis—even dressing like them in inexpensive versions of their gowns, suits, and lingerie offered in department stores.

In spite of the Depression, fashion illustrators were a busy lot, enlivening the pages of publications in France, England and America. They created stunning cover art, enhanced advertising campaigns, and produced hundreds of full-page illustrations, marginal drawings, and vignettes inducing women to buy—consequently keeping the fashion industry afloat. The number of design schools rose dramatically, offering the training which hopefully would lead to employment. New York’s School of Applied Design for Women, The Traphagen School of Fashion and Chicago’s Academy of Fashion Art now competed with the New York School of Fine and Applied Art (Parsons School of Design), Pratt Institute, and Pittsburgh’s Art Institute. They offered instruction in the specialized art of fashion illustration, for the first time described as an applied art, to distinguish it from easel painting. No longer a unique expression of the fine artist, fashion illustration became a profession available to all who could master it.

During the Depression women’s magazines suggested ingenious ways to stretch a wardrobe. In this illustration, a brown suit is given four incarnations by changing the hat and the treatment of the notched collar. The woman remains the serene and practical Thirties Ideal.

In addition to art institutes, there were numerous studio schools run by successful artists, and dozens of inexpensive how-to books for sale, which promised to reveal the arcana necessary to succeed in this glamorous field. The roster of fashion illustrators grew as well. By the late Thirties, luminaries such as Carl Erickson, Ruth Graftstrom, René Bouét-Willaumez (RBW), Eduardo Benito, Jean Pagès, and Pierre Mourgue were joined by new stars: Christian (Bébé) Berard, Marcel Vertès, and René Bouché. Carl Erickson, married to the fashion illustrator Lee Creelman, surpassed her in fame and, like Garbo or Paganini, was known by a single name: Eric. He was born in Illinois and trained at the Chicago Art Institute, and could be spotted in London, Paris, or New York in a three-piece suit, homburg, walking stick, and white boutonniere, often accompanied by a towering model. Eric died in 1958 at 67 years of age.

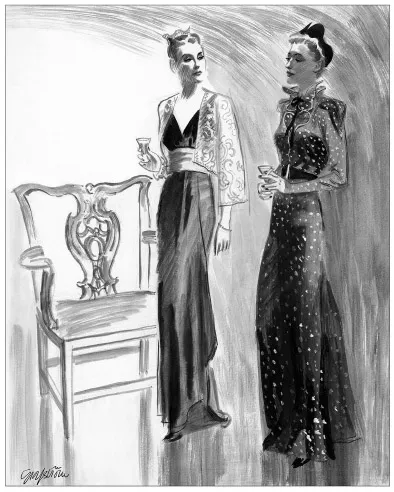

Graftstrom, Vogue, Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast.

The young, attractive Ruth Grafstrom made her mark in Vogue in the Thirties, illustrating the womanly Ideal—soigné, yet warm and receptive. In this 1938 wash drawing, “real” women in soft, feminine gowns inhabit “real” space, complete with Chippendale chair.

The need to illustrate inexpensive clothing in newspapers, catalogs, and pattern books, as well as the desire to continue to represent couture, gave rise to two types of fashion illustration. Retail advertising, which showed particular styles to the woman on a budget and provided information on sizes, cost and availability, created a vast need for literal or “tight” artwork, supplied by a multitude of trained fashion artists, many of whom remain anonymous. Editorial illustrations, on the other hand—more evocative or anecdotal—were seen in glossy magazines for the socialite, and were produced by masters of the genre, often recruited from stage design (Christian Berard), the fine arts (Eduardo Garcia Benito), or portraiture (Cecil Beaton). Improvements in chromo-lithography allowed these stars to create superb full-color fashion illustrations, rivaling easel painting in their authenticity.

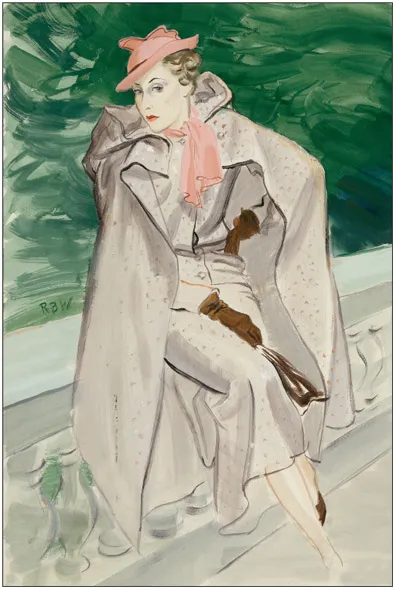

The image of the Ideal, however, remained the same in both categories, and most illustrators continued to draw the elongated, stylized, polished figures of the Twenties. The work was largely in black and white, in homage to the cinema perhaps, but certainly cheaper to reproduce. The poses were lady-like and restrained, arms were held close to the body, clutching a purse or fur piece, one knee slightly bent to give a graceful curve to the longer skirt. The shoulders were squared, the waist defined, and hips often were swiveled to present the narrowest view. The faces were even-featured and impassive, the figure a model of composure.

Bouët-Williaumez, Vogue, Condé Nast Archive. Copyright © Condé Nast.

Known for his fluid brush line and broad, loose washes, René Bouèt-Willaumez (RBW) competed with Eric for preeminence in Vogue. His realistic treatment of the Thirties woman includes the bony structure around the eye, creases in the clothing, and the easy pose of a self-assured woman. Her cape, jacket and skirt will see her from spring through fall and winter.

The two-dimensionality of fashion illustrations from the Twenties expressed the rectilinear quality of the clothing and the ideal boyish body under it. In the Thirties, as a more womanly figure became fashionable, heightened by satin, bias-cut gowns, and the focus on bosom and hips, a more sculptural rendering of the Ideal seemed appropriate. A high degree of realism was introduced in the work of Eric and RBW. These artists worked exclusively from life, and it was possible to recognize the often-photographed models who had also posed for the illustrations. In these drawings the features are softened, hair can be caressed, and clothing conforms to the underlying female anatomy. Through the use of variegated watercolor washes, an expressive brush line, and modeling, the images express a three-dimensional world. It appears that the economic realities of the Thirties needed to be faced squarely by “real” women—a subliminal need that was being satisfied by fashion illustrators and, increasingly, by photography.

By the late Thirties, an upswing in both mood and economics became apparent. A suppleness appeared in gathered and shirred dresses; a playfulness in amusing jewelry and hats; a broader perspective in the adaptation of ethnic embroideries and costume. Dirndls were fashionable, the fullness of the skirt setting off a tiny waist. However, this was a mere respite and the strength and resiliency that had served the womanly Ideal so well during the Depression would be sorely needed to face the challenging realities of the next decade.

The Forties were dominated by the Second World War, beginning with Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, and ending with the devastation of Hiroshima in 1945. As in the First World War, British, French and American women responded briskly and gallantly to the call to arms. They once again donned nurses’ uniforms and took the driver’s seat in ambulances, metros, and delivery trucks and on plows and tractors. In Great Britain and America, women’s most important contribution was the manufacture of planes, ships, and tanks needed for defense. Women welded, riveted, assembled motors and precision instruments, inspected parts, worked in steel mills and munitions plants. They came from every social stratum: heiresses and stenographers, models and waitresses, career girls and housewives—working with enormous esprit de corps in demanding and often dangerous conditions. The ubiquitous Ponds ads in magazines could have been rewritten to express more accurately the ethos of the day: “She’s engaged! She’s lovely! She handles high explosives!”

The outcome of the war depended on the spirit of the fighting men, and keeping them fit in mind and body was seen as women’s highest mission. On the home front the focus was on the furlough, when women often had only “one hour to make a memory.” In spite of restrictions, clothes and accessories were designed to please the men, and magazines were filled with exhortations to look “gay,” “pretty,”and “romantic.” Vogue’s call to arms was clear: “Beauty is your duty … None but the fair deserve the brave.” Polls were taken to determine exactly what men found attractive, with somewhat unexpected results. A 1942 survey of over 300 servicemen published in Vogue discovered fairly conservative tastes (nothing eccentric, please!). The majority preferred dresses to slacks, hats to bare heads, natural hair color and soft makeup. Service women were advised to wear civies when off duty, since fighting men felt women lost half their charm when in uniform. Vogue reported in 1944 that Meyer Davis, Jr., son of the wel...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction by Harold Koda

- The Temptress

- The Garçonne

- The Grown-Up and The Glamour Girl

- The Princess

- Twiggies and Hippies

- The Jetsetter

- The Fashionista

- The Lady or The Tiger

- Picture Credits

- List of Illustrators

- References

- Acknowledgements

- Back Cover