1

BODIES OF FRENCH ALGERIAN LAW

In January 1832, an Algerian notable lodged a complaint before the chief French military commander of the newly conquered territory, General Anne Jean Marie René Savary, the Duke of Rovigo. The man was clearly in a state of emotional distress. According to Rovigo’s report to the minister of war, the man was “in tears and complained of the abduction [rapt] of his two sisters and his wife by a European who had been holding them for three days.” Accompanied by the French-appointed agha (chief) of Arabs, El Hadj Mahiddin, the betrayed husband beseeched the general to return his wife to him. In his notorious military policy, Rovigo systematically violated Algerian lives, beliefs, and belongings, but he displayed remarkable solicitude in this case. The suspected seducer, called in for interrogation alongside the women, admitted to conducting a clandestine affair with the man’s wife, having gone as far as to rent the house next door. The seducer, Rovigo was dismayed to learn, was a judge on the Court of Appeals of Algiers, a certain M. Colombon.1

The infamously violent French military commander rapidly responded to the scandal. A Napoleonic war hero who had served in the Egyptian campaign, he pursued a policy of extensive military colonization with little heed for the nice-ties of law: he authorized extralegal massacres and summary executions, most notoriously of the El Ouffia tribe; converted mosques into cathedrals; destroyed cemeteries to create roads across the capital; and expropriated buildings without regard for titles.2 His actions regularly contravened the protections extended to Algerians by the July 5, 1830, Convention of Capitulation. In this case, however, Rovigo acted against the French official, “forced by the general interest to enact a harsh measure and to treat the natives with equity.” He put Colombon under house arrest and soon deported him to the metropole. Leaving the judge unpunished would, he claimed, disrupt “all of the Maures’ authority over their women.” In his view, they sought “vengeance for the assault on a law that remains a matter of religion.”3

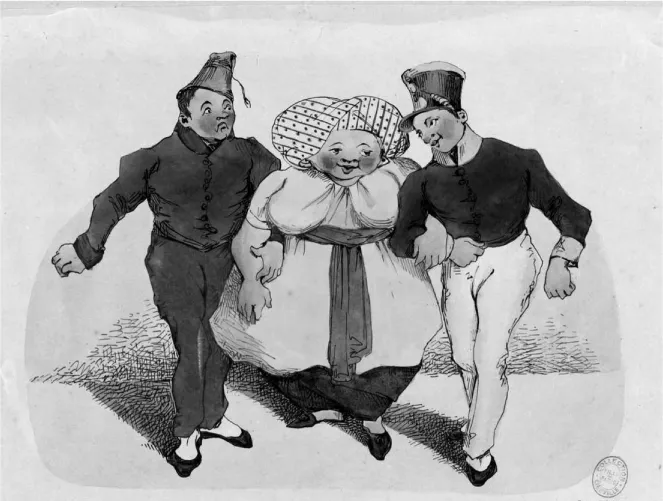

Rovigo acted quickly to correct the French magistrate’s sexual affront to local “religious” law by restoring patriarchal authority. In doing so, he worked to reverse the widespread images of French soldiers as agents of sexual license and plunder in the earliest days of the conquest. One contemporary lithograph playfully drew a direct connection between Algerian women’s apostasy and sexual corruption in its depiction of two naïve soldiers competing for the affections of a faithless woman, “une infidèle.” Rovigo, by contrast, presented himself as a defender of Algerian women’s religious and sexual honor. The case illustrates how French officials variably constructed the boundaries of religious belief and practice in an effort to secure sovereignty. Rovigo had considerable latitude in determining what mattered for the Muslim religion, viewing the assault on the husband’s sexual rights as particularly sensitive. It represented a challenge not only to local men’s authority, but also to his own. As he explained, “Had I not accorded them a dazzling [éclatant] justice, all that I had accomplished with the Arabs would be forever lost.”4 In affirming an intimate connection between religion and patriarchal rights, Rovigo sought to buttress his own legitimacy and power. As this chapter makes clear, his gesture presumed that Muslim religion was bound to Algerian women and their legal status.

This dramatic contest between military, civil, and local authority condensed broader struggles over how to establish French sovereignty and law in the ex-regency. Because the ultimate fate of the territory as a French possession remained insecure, these early years are often characterized as a “period of uncertainty.”5 In this chapter, I show how this insecurity extended beyond military planning to shape debates about law in the nascent colony. “Uncertainty” was, in other words, an epistemological and legal problem, precisely because the very meaning of “law” in the territory was unclear. Between the signing of the July 5, 1830, convention and the July 22, 1834, ordinance that annexed Algerian territory to France, military commanders, civilian officials, metropolitan politicians, and local notables struggled to assert and preserve their authority by making competing claims about legality. Over the course of four years, gendered fantasies of law, religion, and religious law worked to ground an otherwise uncertain colonial order. Far from converting or “liberating” women, these fantasies located Algerian women in the presumptively private domain of their family.

FIGURE 4 / Cornille (Victor Auguste Laurent), Une infidèle, lithograph, 1830. Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet.

Official concerns with legality emerged in response to the wanton destruction wrought by unchecked military force. The Convention of 1830 signed between General Bourmont and the Ottoman regent Hussein Dey was supposed to bring hostilities to an end, extending protections to a diverse local population of an estimated four million Arabs, Berbers, and Jews.6 It dissolved the “foreign” Turkish government, while promising to respect the territory’s indigenous residents, proclaiming: “The freedom of the inhabitants of all classes, their religion, their property, their commerce and their industry, will not be disturbed. Their women will be respected.”7 The French army immediately violated this law of peace. The pillaging of the ex-regency’s capital continued long after the convention’s signing, as soldiers seized private and public belongings, destroyed buildings, and laid claim to pious foundations (habous). Terrorized, thousands of residents fled the capital city. War continued as the army sought to extend French control beyond Algiers. In November 1830, General Bertrand Clauzel ordered the nearby town of Blida to be sacked in response to local resistance. This massacre of hundreds of inhabitants, including women and children, made it clear that the army had no intention of respecting the terms of the convention. While Clauzel’s successor, General Pierre Berthezène, promised to act with greater respect toward the local population, his tenure was short-lived. With Rovigo, violent exactions and terror returned as the order of the day.8

When Rovigo assumed command in late 1831, the army had conquered Algiers and some of the surrounding coastal plains, but only provisional structures of government were in place. Alongside the military commander, a civil intendant, Louis André Pichon, was named to oversee civil matters, thus giving rise to chronic conflicts over authority. In this moment of political indecision, the future of the territory’s relationship to France was tenuous, under vigorous assault from local resistance and metropolitan ambivalence toward a confused and costly colonial project.

Unfolding in this chaotic context, the apparently minor incident regarding Colombon’s sexual dalliance raised larger questions about the relationship between French and local “religious” law, military and civil power, force and right. The limits of brute military violence of the kind exercised by Rovigo became increasingly clear to politicians in Paris who sought to institute a durable colonial government. Intendant Pichon pursued the stabilization of French sovereignty through regularized laws, not personal military rule. He denounced Rovigo’s Napoleonic military fantasy of domination, which remained inadequate “for Algiers as for Egypt.” For Pichon and other critics of military excess, the government had been misled by Napoleonic myths, which amounted to nothing more than a “novel of Algiers.”9 As these contemporary controversies made clear, such fictions had real, indeed devastating, effects.

French officials sought a viable legal solution to the military and epistemological problem of the ex-regency’s fate. Erupting in this uncertain context, the Colombon Affair symptomatically inspired its own novel, staged as a fantasy about men’s sexual and legal control of Algerian women. Fantasy, as I understand it here, both enacts and seeks to answer fundamental epistemological problems. The novel sheds light on the Colombon Affair as a “primal scene” of colonial legal fantasy. That is to say, it demonstrates how gendered fantasies were generated in response to originary questions in the colony—including about the structure and organization of law.10

From the incident of the kidnapped wife in the Colombon Affair to controversies over women’s efforts to escape Muslim law by conversion to Catholicism, Algerian women provoked French officials’ legal thought and desire. They came to embody broader concerns about the prospects of French colonization. As scenes of affective and erotic investment, gendered fantasies about women’s place in Muslim law and religion came to ground a regime of colonial law that was eventually adopted in 1834. By focusing on gender, this chapter offers new insight into how the “period of uncertainty” was fantasmatically staged and provisionally resolved in law.

Originary Fantasies

Fantasies about Muslim men’s patriarchal rights evidently shaped Rovigo’s response to the Algerian husband’s plea. The general decided to release the women, who were from a prominent family, to their brother and husband, after receiving assurances from the city’s principal Muslim qadi and the Agha Mahiddin that they would not be harmed under “Turkish law.” Concerned about rumors that the women had been imprisoned and even killed, the agha assured Rovigo that their “isolation” had “shielded them from insults,” given how the affair “dishonored the family.” Confirming Rovigo’s conception of Algerian patriarchy, Mahiddin expressed gratitude for the “good action that conformed to our religious principles.”11 In disciplining both Colombon and the women, the general shaped the official meaning of “religion” and lent it the backing of French armed force. With the apparent restoration of religious and social order, the women disappear from the state record.12

Rovigo’s punitive force demonstrated masculine and military authority not only to the Algerian notables and tribal leaders, but also to French civil officials whose competing authority he rejected. The women’s uncertain jurisdiction troubled the relationship not just between the general and the indigenous male elite, but also between French officials. They were, in other words, a “ground” for struggles between men.13

The general’s disciplinary actions exacerbated a bre...