Chapter 1

Conquering and Delimiting Transnistria

Before the Romanian occupation, Transnistria did not exist as a territorial-administrative entity. Meaning “the territory beyond the Dniester River” in Romanian, the term had a half-mystical connotation as the region in which lost ethnic Romanian “brothers” resided. In the interwar period, this notion was popularized by ethnic Romanian émigrés from southern Ukraine who escaped the trepidations of the Russian Civil War in Romania. The Romanian government secretly supported their propaganda, possibly as a counterweight to Soviet claims over Bessarabia, but did so intermittently and unenthusiastically. Romania never laid official claims to the region. Thus, the decision to occupy the region militarily and administer it during the war was a novelty in Romanian statecraft. This chapter explores the context within which Transnistria emerged as a legal and administrative reality as well as the Romanian policymakers’ visions and calculations that culminated in its formation.

The Conquest

Romanian occupation of Transnistria was an outgrowth of the country’s participation in the war against the Soviet Union alongside Nazi Germany. Although initially there was a wide consensus in Romanian society behind such participation, Romanian troops’ role in the conquest of the territory to the east of the Dniester River—a de facto Soviet-Romanian border between 1918 and 1940—was controversial from the beginning. This fact cast a shadow over Romanian rule in the province from 1941 to 1944.

When on June 22, 1941, Romania went to war against the Soviet Union, the country was united behind its leader’s, General Ion Antonescu, decision to align the nation to Nazi Germany in order to exact revenge on Soviet empire. The previous summer, Romania suffered a series of humiliations at the hands of its neighbors who forced her to cede parts of her territory: first, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina to the Soviets, then northern Transylvania to Hungarians, and finally, southern Dobrudzha (Dobrogea) to Bulgaria. After the fall of France, Romania’s principal ally in the 1920s and 1930s, Germany and Soviet Russia remained the only serious military powers on the European continent. Although it was Germany who forced Romania to cede its territories to Hungary and Bulgaria, Romanians saw the Soviets as a more immediate danger than the Germans. After the annexation of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina in late June 1940, the Soviets continued to threaten Romanian interests claiming special rights in the Danube Delta. Romanians feared a full-scale Russian invasion, and they might have been correct about it.1

Under such conditions, both the last government under King Carol II headed by Ion Gigurtu, and Ion Antonescu who was appointed by Carol as dictator (Conducător) on September 4, 1940 and then ousted the unpopular king from the throne on September 6, chose an alliance with Germany as the only way to protect the country from continuous Soviet threat.2 Ion Antonescu decided to join Germany in the war against the Soviet Union in late 1940 or early 1941 single-handedly but the decision had unanimous support in his own government, most of Romania’s political class, and the country at large. Almost everybody agreed that the country needed to use this moment to avenge its humiliation at the hands of the Soviets and take Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, annexed the previous summer by the country’s eastern neighbor, back. Besides, Romanian propertied classes hated Bolshevik system and preferred, in their great majority, fascist dictatorship to Soviet-type communism.3

This is why when, on July 5, Romanian troops entered the capital of Bukovina, Cernăuţi, and on July 16, the capital of Bessarabia, Chişinău, the country was euphoric. Ion Antonescu was on the peak of his popularity and quickly rose through the army ranks, conferring upon himself the rank of marshal on August 21, 1941. Eulogized as a liberator of the enslaved provinces, he claimed to his credit the role of a commander of the “Army Group General Antonescu” that drove the Soviets from eastern Romanian lands. The group combined the Third Romanian Army (under General Petre Dumitrescu) that acted in northern Bukovina and northern Bessarabia, the Fourth Romanian Army (under General Nicolae Ciupercă) that acted in southern Bessarabia, and German Eleventh Army (under General Eugen Siegfried Erich Ritter von Schobert) that acted in northern and central Bessarabia. This arrangement, suggested by Hitler during his meeting with Antonescu on July 12 in Munich and clarified in the following exchange of letters between the two, ostensibly put German troops under the Romanian command for the first time in history. However, it was devoid of real substance: German Eleventh Army’s High Command served as “work staff” of the “General Antonescu Army Group” with its orders to the Romanian units overseen and signed by Antonescu who, in turn, answered to the High Command of Wehrmacht and Hitler. The General Antonescu Army Group lasted only as long as the troops operated within the 1939 Romanian borders. As soon as they passed the Dniester River on July 17, the group was shut down.4

If this act was intended to signify the end of the Romanian army participation in the war, the reality proved otherwise. Romanian troops continued their advance eastward in the steps of their mighty ally. It is not exactly clear when the decision to pass the Dniester River was made by Antonescu but on July 27, 1941, Hitler in his letter to Conducător commended him for his determination to wage the war “alongside Germany until the very end.”5 At the time, the Third Army was already advancing toward the southern Buh River in what was to become northern Transnistria. A day before the Fourth Army completed the reconquest of southern Bessarabia and was advancing across the Dniester River in the direction of Odessa, to which they lay siege on August 5. On July 31, Antonescu, in a letter to Hitler profusely and grovelingly thanked him for his appreciation of Romanian bravery and confirmed his resolve to “go to the end in the action that I started in the east against the great enemy of civilization, of Europe, and of my country: Russian Bolshevism.”6 During his meeting with Hitler on August 6 in the Ukrainian town of Berdychiv, Antonescu explained his immediate military plans more precisely: to occupy not only Transnistria but also Crimea from which Soviet air force threatened Romanian port city of Constanţa.7

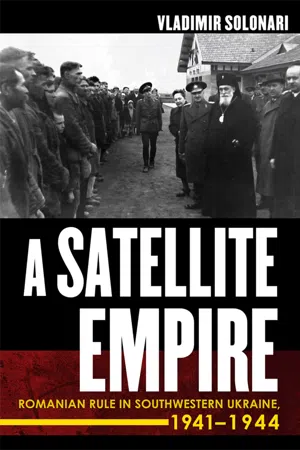

Figure 1. The Soviet prisoners of war taken in the first weeks of the war by the Romanians. Photo: Army Propaganda Department. Original caption reads, “This riff-raff stripped of their humanity by indoctrination and alcohol just yesterday was Stalin’s army’s best. Today the guards drive them into the camps.” Courtesy DANIC.

Although Romanians agreed that their eastern provinces had to be taken back from the Soviets, and Germany’s attack on the USSR was the right moment to do so, they were not in accord on the participation in the war farther to the east. As Romanian losses mounted, doubts increased. On August 8, 1941, Ion Antonescu ordered the Fourth Army to capture Odessa “on the march.” This, as it turned out, was an unrealistic order since by that time the Soviets heavily fortified the city from the attack from the north by land troops (before the war’s outbreak, Soviet plans appreciated the likelihood of such an attack as low and consequently, the city was fortified on the shores only). Three defense lines of barbed wire, trenches, dugouts, machine gun and artillery nests ran around the city in three semicircles starting from as far away as thirty kilometers. The city was defended by the force of no less than 90,000 troops constantly reinforced by fresh compliments transported by sea and supported by gunfire from the Soviet naval force.8 Romanian intelligence failed to alert the Romanian High Command to the strengths of the Soviet defenses and their determination to retain the city. When on August 20, General Eugen Siegfried Erich Ritter von Schobert, commander of the Eleventh German Army offered German assistance to the Fourth Romanian Army charged with capturing Odessa, Ion Antonescu turned down this offer on the ground that Romanian forces were sufficient to accomplish the task and assured his counterpart that Odessa would be taken “by early September as the latest.”9

Two Romanian assaults, between August 8–24 and August 28–September 5, were poorly prepared and badly executed. As the result, they failed to produce the desired success and instead resulted in casualties of no less than 58,859, of whom 11,046 dead, 42,331 wounded, and 5,478 missing in action.10 On September 3, 1941, commander of the Fourth Army General Nicolae Ciupercă forwarded a memorandum to Ion Antonescu in which he opined that “nearly all our divisions have exhausted their offensive potential, both physically and morally,” while the enemy was “taking full advantage of his control of the sea to reinforce Odessa.” He advised the Conducător against further frontal attacks.11 In response, on September 9, Antonescu dismissed Ciupercă “for lack of offensive spirit” and appointed in his stead his Minister of Defense general Iosif Iacobici who revised Ciupercă’s plan of assault on the city. However, the third offensive carried out by Iacobici on September 12–21, was no less disastrous than the previous two, leading to further enormous casualties.12

Further Romanian setback came when the Soviet combined land, marine, and airborne forces launched a surprise attack against their positions on the seashore to the east and west of the city on September 21 and October 2. Romanian troops retreated, sometimes in panic. Many gains attained in the previous months were lost and Antonescu had to request, to his chagrin, support in infantry and air force from the Germans. Seeing Romanian humiliations at Odessa, the Germans honored this request and dispatched an infantry division and heavy artillery contingent freed after their crushing victory over the Soviets at Kyiv.13 By the time their reinforcements arrived in early October, the Soviets had already abandoned Odessa. Soviet plans changed under the pressure of developments on the fronts farther to the east in southern Ukraine. The German victory in the battle of the Perekop Isthmus, which connects the Crimean Peninsula with mainland led to a drastic deterioration of Soviet positions in Crimea. With Sevastopol, the main naval Soviet base, threatened on land by the quickly advancing German troops, Odessa lost its strategic importance for the Soviets. Consequently, the Soviet High Command decided to concentrate all available forces on Sevastopol’s defense. From October 2 through October 16, the bulk of the Soviet forces successfully evacuated from Odessa into Crimea by sea. Romanian forces resumed their attacks on the city on October 15 and, without encountering serious resistance, entered Odessa the next dat. Their third major offensive scheduled to start on October 20 never took place. Romanian losses in the battle of Odessa reached staggering 90,020, of whom 17,891 dead, 63,280 wounded, and 8,849 missing in action. The number of losses at Odessa represented an unsustainable 26.46 percent of the total forces engaged there, 340,223 out of 583,930 men of the overall Romanian land force. This was substantially higher than the share of German losses on the Eastern Front as a whole by September 30, 1941—17.22 percent.14

General Ciupercă was not the only military top brass opposed to Antonescu’s reckless strategy at Odessa. According to Ioan Hudiţa, deputy secretary general of the oppositional National Peasants Party (PNŢ)—that was ostensibly banned alongside all other parties and political organizations but in reality continued to function in a semi-clandestine fashion—this was also the opinion of the under secretary of state at the Ministry of National Defense general Gheorge Jienescu. As Hudiţa wrote in his diary on July 10, Jienescu felt that the cost of front assaults ordered by Antonescu contrary to German advice was too high and that many other generals believed the same but, minding Antonescu’s vengefulness, were loath to confront him over the issue.15 According to the assessment by the Romanian General Staff, the morale of the troops engaged at Odessa was considerably lower than the one they displayed during fighting in Bessarabia. The recovery of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina was worth the fight, whereas the rationale of the war beyond the Dniester was beyond them.16

Inordinately high Romanian losses dampened societal support for the war. On August 13, Hudiţa wrote in his diary during his father’s visit to Bucharest. A schoolteacher from the village of Bogdăneşti in northern Moldova, he told his son that in this village and others around it residents were mourning the death of hundreds of young men killed at Odessa. People “were cursing Antonescu [and] the alliance with Hitler.”17 During his visit to Bogdăneşti on September 7, 1941, Hudiţa confirmed widespread popular resistance to the continuation of the war beyond the Dniester.18

In Hudiţa’s party opinions were divided as to the wisdom of continuing military operations beyond the Dniester, but its leader Iuliu Maniu, a well-respected nationalist democrat from Transylvania and former prime minister, as well as Hudiţa himself, resolutely opposed this policy. On July 23, Maniu sent a memorandum to Antonescu in which he, in the name of his party, praised the dictator for regaining Bessarabia and northern Bukovina but warned him against waging the war to the east of those provinces. “It is inadmissible for us to appear as aggressors against Russia, today an ally of England, which will probably be a victor [in the war],” he wrote prophetically.19 In the other powerful opposition party, the National Liberals were more in favor of Antonescu’s policy of continuous war but its leader Dinu Brătianu was in full agreement with Maniu on the issue.20

On the international arena, Romania’s actions beyond the Dniester had grave consequences. On November 30, 1941, Great Britain presented an ultimatum, requesting withdrawal of Romanian military back to the 1939 borders within five days. When the Romanians did not budge, Great Britain declared war on Romania on December 6; British dominions of Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South African Union followed suit.21 This was a nightmare—a Western power and traditional ally of Romania, now at war with their country—that even some members of the ruling circle wanted to avoid. According to General Jienescu, who desperately tried to pe...