- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

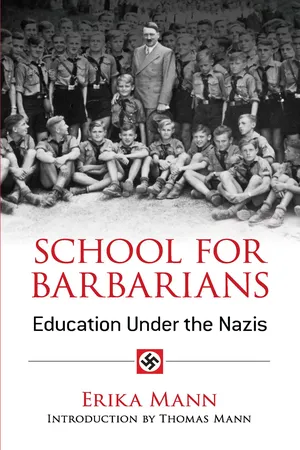

Published in 1938, when Nazi power was approaching its zenith, this well-documented indictment reveals the systematic brainwashing of Germany's youth. The Nazi program prepared for its future with a fanatical focus on national preeminence and warlike readiness that dominated every department and phase of education. Methods included alienating children from their parents, promoting notions of racial superiority instead of science, and developing a cult of personality centered on Hitler.

Erika Mann, a member of the World War II generation of German youth, observed firsthand the Third Reich's perversion of a once-proud school system and the systematic poisoning of family life. This edition of her historic exposé features an Introduction by her father, famed author and Nobel laureate Thomas Mann.

Erika Mann, a member of the World War II generation of German youth, observed firsthand the Third Reich's perversion of a once-proud school system and the systematic poisoning of family life. This edition of her historic exposé features an Introduction by her father, famed author and Nobel laureate Thomas Mann.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access School for Barbarians by Erika Mann, Thomas Mann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE SCHOOL

UNTIL RECENTLY, GERMAN schools had the world’s respect: the relationship between teachers and pupils, especially just after the War, was human and dignified, and the teachers themselves were distinguished for thoroughness, discipline, and scientific exactness. The grammar schools and Gymnasien (high schools), colleges and universities, were open to all, and their moderate tuition fees were canceled for talented students of limited means. There were some, like the best American boarding schools, in beautiful, healthful places, whose modern methods allowed teacher and pupils to sit in the garden and have lessons that were remembered as stimulating conversation, or to make excursions over the hills and fields. There were performances in the school theaters, and films shown to supplement courses in natural science, history, and geography.

One subject, political propaganda, was missing from the curriculum. The German Republic refused to influence its citizens one way or the other, or to convince them of the advantages of democracy; it did not carry on any propaganda in its own favor. This proves to have been an error; and its atonement has been a terrible one. Whatever its cause, modesty or the waverings of a young and unconfident Republic, the error stands. What the Republic did toward education was done as a matter of course. Civic buildings, for peacetime use, were put up, and of these many were schools — airy, spacious, and happily adequate. They were set into service without propaganda or hullabaloo. The State was the people’s servant; it served in quiet, believing that its master, the people, would be thankful. But the State was wrong.

Unused to self-rule, the German people submitted to a new State which made itself the master, and forced the people to be its servants. The State and its Führer entered their power in a frenzy of display. The Fiihrer and his followers, shouting and raving, were the opposites of the old, submissive, quiet State. They praised their ideas as the only road to salvation; they commanded; they dictated.

What had been the field of politicians before, and known as “politics,” was now a Weltanschauung (philosophy of life), no less, and there was no other than the National Socialist Weltanschauung. It soon forced itself into the schools, changing them, making rules, interdicting, innovating, and completely changing their character within a few months.

Had the “old-fashioned” educators tried to make civilized human beings of the children in their care? Had they encouraged them in their search for truth? Left youth as much personal freedom as they thought compatible with discipline? Taken them to theaters and movies to serve educational purposes? Had they done all of this? It must all go, according to the Nazis, immediately and radically. Morals, truth, freedom, humanitarianism, peace, education — they were errors that corrupted the young, stupidities with no value to the Führer. “The purpose of our education,” he was crying, “is to create the political soldier. The only difference between him and the active soldier is that he is less specially trained.”

The changes were extensive and thorough. Where good educational methods remained, they were not new ones, but those taken over from the Republican German Youth Movement, from the progressive schools, or from Russian or American experiments. The new methods were recognizable by their violence and brutality. There was only one entirely new and entirely different idea: the purpose to which the new education was dedicated. And that purpose was the aims and plans of the Führer.

In Mein Kampf there is a short chapter devoted to the problem of the education of children, (Translator’s note: This chapter does not exist in the authorized American edition. There is a condensed version of the passages quoted here, in the chapter “The State,” pp. 167-175, from which the passages marked with asterisks are taken.) It contains the proposals of the Führer in this field, and all German children grow up today in the materialism expressed in these twenty-five pages.

“Principles for scientific schools. ... In the first place, the youthful brain must not be burdened with subjects, 90 per cent of which it does not need and therefore forgets again.”* And “. . . it is incomprehensible why, in the course of years, millions of men must learn two or three foreign languages which they can use for only a fraction of that time, and so, also in the majority, forget them completely; for of 100,000 pupils who learn French, for example, scarcely 2,000 will have a serious use for this knowledge later, while 98,000 in the whole course of their lives will not be in a position to use practically what they have learned. . . . So, for the sake of the 2,000 people to whom the knowledge of these languages is of use, 98,000 are deviled for nothing, and waste precious time. . . .”

His aversion for knowledge is strong and sincere. He has refused learning, and seems, even as a child, to have been “deviled for nothing.” Also, it is necessary for the dictatorship to keep the people as ignorant as it can; only while the people remain unsuspecting, unaware of the truths of the past and present, can the dictatorship unleash its lies.

“Faith is harder to shake than knowledge,” he continues. “Love succumbs less than respect to change, hate lasts longer than aversion, and the impetus toward the most powerful upheavals on this earth has rested at all times less in a scientific knowledge ruling the masses than in a fanaticism blessing them, and often in a hysteria that drove them forwards.”

This is the positive force that is to take the place of the 90 per cent of school material which Hitler brands as superfluous. “Faith” — in the Führer, and the truth about him concealed; “Love”—for the Führer, with respect conceded as unworthy; “Hate” — of enemies whom mere “aversion” could not destroy; and, above all, the hysteria which is checked by scientific knowledge, the “fanaticism blessing” the masses.

The positive force is summed up: “The whole end of education in a people’s State, and its crown, is found by burning into the heart and brain of the youth entrusted to it an instinctive and comprehended sense of race. ... It is the duty of a national State to see to it that a history of the world is eventually written in which the question of race shall occupy a predominant position. . . .* According to this plan, the curriculum must be built up with this point of view. According to this plan, education must so be arranged that the young person leaving school is not half pacifist, democrat or what have you, but a complete German. . . . Also, in this case (for girls), the greatest importance is to be given the development of the body, and only after that on the requirements of the mind, and finally of the soul. The aim of the education of women must be inflexibly that of the future mother.”

The Epilogue of Mein Kampf expresses in all clearness the whole purpose of education in Nazi Germany. “A state which, in the era of race-poisoning, devotes itself to the care of its best racial elements must one day become master of the world.”

That is the aim: to make the Nazis the rulers of the world. It is towards this that Hitler stares, that Germany is equipping itself; this is fixed before the eyes of the children,

DR. RUST AND OTHER EDUCATORS

After a year of preparation, transition and experiment in the schools, Hitler’s educational program was made effective on April 30, 1934, the day on which Dr. Bernhard Rust was appointed “Reich Minister of Science, Education, and Culture For the People (Volksbildung).” Dr. Rust, an unemployed teacher from Hanover, had belonged to the Nazi Party since 1922. In 1925, he was promoted to the post of Gauleiter of the Party for the district of Hanover and Brunswick. He held office as educator of the republican democratic youth of his home town until 1930. Indeed, it seemed not to be his political activities against the State, whose employee he was, that led to his dismissal, but rather his nervous disorder, which was causing violent attacks of complete insanity at increasingly short periods. Dr. Rust was forced to take longer and longer holidays at sanatoriums, and the State could not hold itself responsible for his ability as a teacher, even during the moments of comparative clarity in the Doctor’s mind.

Bernhard Rust had been decorated with the Iron Cross during the War, and had written about his experience in these terms to his son: “Received today under the thunder of guns the Iron Cross. Your hero father.”

It’s a good story: Rust rises in the Party, to which the ex-teacher seems highly learned, and lands his post right after the success of the grab for power. He moves up with increasing momentum. As early as February, 1933, he is Prussian Minister of Culture, and a year later he is promoted to Dictator of Education. He has held his office with the dilettante laxness characteristic of Nazi administration, and with the nervous unpredictable jitters that, four years before, had taken away his teacher’s job. Rust makes laws now, and repeals them when he has convinced himself of their total impracticability. He not only reduced the period of compulsory public school training from thirteen years to twelve; he went farther, and tried to cut the school week. It had always been customary in Germany to go to school six days out of the seven, with only Sunday as holiday. By an edict of June 7, 1934, Rust canceled Saturday, calling it the “Reich Youth Day.” On Saturdays there were to be no lessons; only “national festivals.”

The curtailed week proved insufficient right away. The demands of the curriculum were too heavy. But the Minister brought everything back on the track, apparently, by means of an invention of his called the “rolling week.” A week began on Monday, went through six school days, omitting Saturday (national festival day) and Sunday (the regular holiday). But the next week was to begin on Tuesday, the one after that on Wednesday, and so on. The result was impossible confusion. And the Minister took months to grasp the fact that, no matter how he rolled his eight-day week, he could never put fifty-two such weeks into a calendar year. At last, rather than devise a new calendar, he decided to call off the whole thing, Reich Youth Day, rolling week, and all.

But by that time there was a new period in the measurement of time. The principal of a German high school, who spends his vacations with relatives in Prague, told them about a “Rust,” which, he explained, was “the period from the moment when the Minister of Education issues an edict to the moment when he revokes it.”

At present, the school week begins on Monday, and includes Saturday, as it used to — or, rather, as never before. For the new spirit has taken hold in the schools since 1934. The teachers, who might as a group have originally had many mental reservations toward Nazism, have fallen completely under its control, and tens of thousands of them — men of science and of the spirit, men with pedagogical experience and a sense of responsibility — are unresisting now, tools to the new leaders’ hands.

Spiritual Germany on its shield, defeated without battle and without honor, presents an image of tragic loss; and those who did oppose the enemy were always heroes, and often martyrs. Even the following passage, although not a notably courageous one, reflects to the credit of the teachers. On March 1, 1933, The Leipzig Teachers’ Journal declared under the heading, “The Field of Ruin”:

“. . . The 250 Reich Ministers whom we have had since 1918 (53 of whom were Democrats and 197 Liberals) were surely none of them without faults; they were not magicians, but at least they were not irresponsible. . . . Has nothing really been done for Germany’s youth since 1918? Did sociologic pedagogics exist only before that time? The Weimar Constitution contributed nothing save freedom in teaching and scientific research (Art. 142), the promise of uniform training for teachers (Art. 143), a State organization for the supervision of schools (Art. 144), the launching of a reorganization of the professional school (Art. 145), the institution of four years of uniform preparation for higher education (Art. 146), the support of students of special talent with limited means, the cancelation of tuition fees and often even of the cost of textbooks. Respect for the opinions of others! . . . Do all these things really, according to the Hitler-Hugenberg Cabinet, deserve to be condemned and done away with, although the teachers during the period in question regarded them as innovations to be gratefully accepted and regard them even today as of great benefit?”

That quotation appeared one month after Hitler came to power. It was the last expression of courage from the German teachers that reached the public. At the same time, the statement seems so naive, so ignorant of the true purposes of the new system as to make its “courage” almost an error of judgment. It also demonstrates the complete unpreparedness of the teachers and their helplessness before what was to take place. They ask blankly whether “freedom of teaching and science” and “consideration of the opinions of others” are to be condemned. “Yes,” comes the answer. “Of course, they are to be condemned and done away with.” And there is no further effort made by the teachers to save their souls.

The psychological and material motives that lie behind such obedience are another matter. But the “Laws,” “Edicts,” “Official Advice,” and other pertinent facts are before us.

In 1937, 97 per cent of all teachers belonged to the National Socialist Teachers Union (N.S.L.B.), according to Reichswalter and District Leader Wächtler; and among these were seven district leaders, seventy-eight Kreis leaders, and over two thousand dignitaries. Seven hundred have won the honor badge of the Party. These teachers are in the service of the movement; they may even be regarded as representative, and as Nazis they cannot be attacked, no matter how they function as teachers.

The Nachrichtenblatt published Herr Wächtler’s photograph: he was in uniform, under a swastika, and looked like a mad corporal who has waked to find himself a general in the field of education.

The steps taken before the issuance of Herr Wächtler’s summary are typical.

The first thing that happened, in the winter of 1933, was that all teachers of “non-Aryan” or Jewish descent were relieved of their posts. An edict was issued on July 11, 1933, that included teachers with all other State officials, ordering them to subordinate their wishes, interests, and demands to the common cause, to devote themselves to the study of National Socialist ideology, and “suggesting” that they familiarize themselves with Mein Kampf. Three days later, a “suggestion” was sent to all those who still maintained contact with the Social Democratic Party, that they inform the Nazi Party of the severance of these connections. Committees were formed to see that it was carried out, and whoever hesitated was instantly dismissed. The purge was on.

It was decided, in Prussia first (November, 1933), and later in all German schools, that public school teachers must belong to a Nazi fighting organization; they were to come to school in uniform, wherever possible, and live i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Heil

- The Family

- The School

- The State Youth

- Epilogue