- 173 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

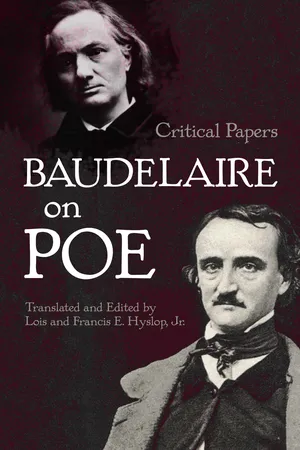

Renowned poet Charles Baudelaire played a significant role in introducing Edgar Allan Poe to French readers by publishing widely read criticisms and translations of Poe's writings. The two writers shared an appreciation for the exotic, a taste for morbid subjects, and a devotion to artistic purity. Baudelaire immersed himself in the study of English for the express purpose of doing justice to Poe's works, and his translations established his reputation in the French literary world well before the publication of his most famous book of poetry, Les Fleurs du Mal.

In the first part of this study, "Edgar Allan Poe, His Life and Works," Baudelaire sketches his subject's biography and discusses several representative writings. Two additional essays analyze Poe's literary theories and offer intriguing reflections of Baudelaire's own sense of aesthetics. The compilation concludes with a critical miscellany of several other prefaces and notes on the American author and his works.

In the first part of this study, "Edgar Allan Poe, His Life and Works," Baudelaire sketches his subject's biography and discusses several representative writings. Two additional essays analyze Poe's literary theories and offer intriguing reflections of Baudelaire's own sense of aesthetics. The compilation concludes with a critical miscellany of several other prefaces and notes on the American author and his works.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Baudelaire on Poe by Charles Baudelaire, Lois and Francis E. Hyslop in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & French Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Sa Vie et Ses Ouvrages: 1852

Il y a des destinées fatales; il existe dans la littér ature de chaque pays des hommes qui portent le mot GUIGNON écrit en caractèrés mystérieux dans les plis sinueux de leurs fronts. Il y a quelque temps, on amenait devant les tribunaux un malheureux qui avait sur le front un tatouage singulier: PAS DE CHANCE. Il portait ainsi partout avec lui l’étiquette de sa vie, comme un livre son titre, et l’interrogatoire prouva que son existence sétait conformée à son écriteau. Dans l’histoire littéraire, il y des fortunes analogues. On dirait que lAnge aveugle de l’expiation s’est emparé de certains hommes, et les fouette a tour de bras pour Vedification des autres. Cependant, vous parcourez attentivement leur vie, et vous leur trouvez des talents, des vertus, de la grace. La société les frappe d’ un anathème special, et argue contre eux des vices de caractere que sa persecution leur a donnés. Que ne fit pas Hoffmann pour désarmer la destinée? Que nentreprit pas Balzac pour conjurer la fortune? Hoffmann fut oblige de se faire brûler l’épine dorsale au moment tant desire où il com-mençait à étre à l’abri du besoin, où les libraires se [The French text ends here.]

There are destinies doomed by fate; among the writers of every country are men who bear the words bad luck written in mysterious characters in the sinuous folds of their foreheads. Recently there appeared in court an unfortunate man whose forehead was marked by a strange tattoo: no luck.1 Thus he carried with him everywhere the label of his life, like the title of a book, and cross-examination showed that his life was in correspondence with this inscription. In literary history there are similar fortunes. One would say that the blind Angel of expiation has seized upon certain men, and whips them with all its might for the edification of others. Nevertheless, if you study their lives carefully, you will find that they possess graces, talents, virtues. Society strikes them with a special curse, and condemns in them weaknesses of character which its persecution has produced. What did not Hoffmann do to disarm destiny? What did not Balzac undertake to charm fortune? Hoffmann had to break his back just when he was beginning to be free of want, when editors were competing for his stories, when he had finally gathered together the precious library dreamed of for so long a time. Balzac had three dreams: a well published edition of all his works, the payment of his debts, and a marriage long contemplated and cherished in the back of his mind. Thanks to labors so numerous that they frighten the imagination of even the most ambitious and the most industrious, the edition was published, the debts were paid, the marriage was realized. No doubt Balzac was happy. But malicious destiny, which had allowed him to put one foot into the promised land, immediately tore him violently away from it. Balzac suffered a horrible death and one worthy of his strength.

Is there then a diabolical Providence which prepares misfortune in the cradle? A man whose somber and desolate talent arouses apprehension is thrown into hostile surroundings with premeditation. A tender and delicate soul, a Vauvenargues,2 slowly puts forth sickly leaves in the coarse atmosphere of a garrison. A spirit fond of the open air and in love with wild nature struggles for a long time behind the suffocating walls of a seminary. A clownish, ironic and ultra-grotesque talent, whose laugh sometimes resembles a hiccup or a sob, finds himself caged up in a vast office full of green file cases, among men with gold-rimmed spectacles. Are there then souls destined for the altar, consecrated, so to speak, who are obliged to march to death and glory through never-ending self-sacrifice? Will the nightmare of Darkness always swallow up these rare spirits? In vain they defend themselves, they take every precaution, they are perfect in prudence. Let us seal every opening, let us double-lock the door, let us bar the windows. But we have forgotten the keyhole; the Devil has already entered.

Their own dog bites them and gives them rabies. A friend will swear that they have betrayed the king.3

Alfred de Vigny has written a book4 to show that a poet has no place either in a republic or in an absolute monarchy, or in a constitutional monarchy; and no one has answered him.

The life of Edgar Poe was a painful tragedy with an ending whose horror was increased by trivial circum-stances. The various documents which I have just read have convinced me that for Poe the United States was a vast cage, a great counting-house, and that throughout his life he made grim efforts to escape the influence of that antipathetic atmosphere. In one of the biographies5 of Poe it is said that if he had been willing to normalize his genius and to apply his creative abilities in a manner more appropriate to the American soil, he could have been a money-making author; that after all, the times are not so difficult for a man of talent, that such a man can always make a living, provided that he is careful and economical, and moderate about material things. Elsewhere, a critic6 writes shamelessly that, however fine the genius of Poe may have been, it would have been better for him to have had only talent, since talent pays off more readily than genius. In a note which we shall see shortly, written by one of his friends, it is admitted that it was difficult to employ Poe for journalistic work, and that it was necessary to pay him less than others, because he wrote in a style too much above the ordinary level. All that reminds me of the odious paternal proverb: make money, my son, honestly if you can, BUT MAKE MONEY. What a commercial smell! as Joseph de Maistre said in speaking about Locke.

If you talk to an American, and if you speak to him about Poe, he will admit his genius; quite willingly even, perhaps he will be proud of it, but he will end by saying in a superior tone: but as for me, I am a practical man; then, with a slightly sardonic air, he will talk to you about the great minds who do not know how to save any-thing; he will tell you about Poe’s disorderly life, about his alcoholic breath which could have been set on fire by a candle, of his errant habits; he will tell you that Poe was an erratic person, a stray planet, that he shifted constantly from New York to Philadelphia, from Boston to Baltimore, from Baltimore to Richmond, And if, your heart already moved by this foretaste of a calamitous existence, you remark that Democracy has its disadvantages, that in spite of its benevolent mask of liberty it perhaps does not always allow the development of individuality, that it is often quite difficult to think and write in a country where there are twenty or thirty million rulers, that moreover you have heard it said that there exists in the United States a tyranny much more cruel and more inexorable than that of a monarchy, namely public opinion,—then you will see his eyes open wide and flash lightning, the slaver of indignant patriotism rise to his lips, and you will hear America, through his mouth, hurl insults at metaphysics and at Europe, her ancient mother. Americans are practical people, proud of their industrial strength, and a little jealous of the old world. They do not have time to feel sorry for a poet who could be driven insane by grief and loneliness. They are so proud of their youthful greatness, they have such a naïve faith in the omnipotence of industry, they are so sure that it will succeed in devouring the Devil, that they feel a certain pity for all these idle dreams. Forward, they say, forward, and let us forget the dead. They would gladly tread upon free and solitary souls, and would trample them underfoot with as much heedlessness as their immense railroads cut through slashed forests, and as their big ships push through the debris of a boat wrecked the day before. They are in such a hurry to succeed. Time and money are all that count.

Some time before Balzac sank into the final abyss, uttering the noble cries of a hero who still had great things to do, Edgar Poe, who resembles him in several ways, fell, stricken by a frightful death. France lost one of its greatest geniuses, and America lost a storyteller, a critic, a philosopher who was hardly made for her. Many persons here are unaware of the death of Edgar Poe, many others believed that he was a rich young gentleman, who wrote little, producing his strange and terrible creations in the midst of a smiling leisure, and who was acquainted with literary life only through a few rare and brilliant successes. The reality was just the contrary.

Poe’s family was one of the most respectable in Baltimore. His grandfather was quartermaster-general in the Revolutionary War, and Lafayette held him in high esteem and affection. The last time that he visited America, he expressed his solemn gratitude to the general’s widow for the services which her husband had rendered him. His great-grandfather had married a daughter of the English admiral McBride, and through him the Poe family was allied with the most illustrious families of England. Edgar’s father was well educated. Having fallen violently in love with a young and beautiful actress, he ran away and married her. In order to join his destiny more closely to hers, he tried to become an actor. Neither of them had the necessary talent, and they lived in a very sorry and a very precarious way. The young wife, nevertheless, managed to succeed through her beauty and the public which she beguiled tolerated her mediocre acting. They arrived at Richmond on one of their tours, and both of them died there, within a few weeks of one another, both from the same cause: hunger, destitution, poverty.

Thus they left to chance an unfortunate little boy, hungry, homeless, friendless, whom nature, however, had endowed with a charming manner. A rich merchant of the town, Mr. Allan, was moved by pity. He was delighted by the pretty little boy and as he had no children, he adopted him.7 Thus Edgar Poe was brought up in comfortable circumstances and was given a complete education. In 1816 he accompanied his foster parents on a journey to England, Scotland and Ireland. Before returning home, they left him with Dr. Bransby, who was the director of an important school at Stoke-Newington, near London, where he spent five years.

All those who have considered their own lives, who have often looked back in order to compare their past with their present, all those who have the habit of psychologizing about themselves, know what an immense part adolescence plays in the final nature of a man. It is then that objects sink their profound imprint into delicate and yielding minds; it is then that colors are intense, and that the senses speak a mysterious language. The character, the genius, the style of a man are formed by the apparently commonplace circumstances of his early youth. If all the men who have occupied the world’s stage had noted their childhood impressions, what an excellent psychological dictionary we would possess! The color, the turn of mind of Edgar Poe make a violent contrast against the background of American literature. His compatriots consider him scarcely American, and yet he is not English. It is fortunate then, to discover in one of his stories, one which is not well known, William Wilson, a singular account of his life at school in Stoke-Newington. All of Edgar Poe’s stories are, so to speak, biographical. The man is to be found in the work. The persons and incidents are the setting and the ornament of his memories.

My earliest recollections of a school-life are connected with a large, rambling, Elizabethan house, in a misty-looking village of England, where were a vast number of gigantic and gnarled trees, and where all the houses were excessively ancient. In truth, it was a dream-like and spirit-soothing place, that venerable old town. At this moment, in fancy, I feel the refreshing chilliness of its deeply-shadowed avenues, inhale the fragrance of its thousand shrubberies, and thrill anew with undefinable delight, at the deep hollow note of the church-bell, breaking, each hour, with sullen and sudden roar, upon the stillness of the dusky atmosphere in which the fretted Gothic steeple lay imbedded and asleep.

It gives me, perhaps, as much of pleasure as I can now in any manner experience, to dwell upon minute recollections of the school and its concerns. Steeped in misery as I am—misery, alas! only too real— I shall be pardoned for seeking relief, however slight and temporary, in the weakness of a few rambling details. These, moreover, utterly trivial, and even ridiculous in themselves, assume, to my fancy, adventitious importance, as connected with a period and a locality when and where I recognize the first ambiguous monitions of the destiny which afterward so fully overshadowed me. Let me then remember.

The house, I have said, was old and irregular. The grounds were extensive, and a high and solid brick wall, topped with a bed of mortar and broken glass, encompassed the whole. This prison-like rampart formed the limit of our domain; beyond it we saw but thrice a week—once every Saturday afternoon, when, attended by two ushers, we were permitted to take brief walks in a body through some of the neighboring fields—and twice during Sunday, when we were paraded in the same formal manner to the morning and evening service in the one church of the village. Of this church the principal of our school was pastor. With how deep a spirit of wonder and perplexity was I wont to regard him from our remote pew in the gallery, as, with step solemn and slow, he ascended the pulpit! This reverend man, with countenance so demurely benign, with robes so glossy and so clerically flowing, with wig so minutely powdered, so rigid and so vast,—could this be he who, of late, with sour visage, and in snuffy habiliments, administered, ferule in hand, the Draconian Laws of the academy? Oh, gigantic paradox, too utterly monstrous for solution!

At an angle of the ponderous wall frowned a more ponderous gate. It was riveted and studded with iron bolts, and surmounted with jagged iron spikes. What impressions of deep awe did it inspire! It was never opened save for the three periodical egressions and ingressions already mentioned; then, in every creak of its mighty hinges, we found a plenitude of mystery—a world of matter for solemn remark, or for more solemn meditation.

The extensive enclosure was irregular in form, having many capacious recesses. Of these, three or four of the largest constituted the playground. It was level, and covered with fine hard gravel. I well remember it had no trees, nor benches, nor any thing similar within it. Of course it was in the rear of the house. In front lay a small parterre, planted with box and other shrubs, but through this sacred division we passed only upon rare occasions indeed— such as a first advent to school or final departure thence, or perhaps, when a parent or friend having called for us, we joyfully took our way home for the Christmas or Midsummer holidays.

But the house!—how quaint an old building was this!—to me how veritable a palace of enchantment! There was really no end to its windings—to its incomprehensible subdivisions. It was difficult, at any given time, to say with certainty upon which of its two stories one happened to be. From each room to every other there was sure to be found three or four steps either in ascent or descent. Then the lateral branches were innumerable—inconceivable—and so returning in upon themselves, that our most exact ideas in regard to the whole mansion were not very far different from those with which we pondered upon infinity. During the five years of my residence here, I was never able to ascertain with precision, in what remote locality lay the little sleeping apartment assigned to myself and some eighteen or twenty other scholars.

The school-room was the largest in the house— I could not help thinking, in the world. It was very long, narrow, and dismally low, with pointed Gothic windows and a ceiling of oak. In a remote and terror-inspiring angle was a square enclosure of eight or ten feet, comprising the sanctum, ‘during hours,’ of our principal, the Reverend Dr. Bransby. It was a solid structure, with massy door, sooner than open which in the absence of the ‘Dominie,’ we would all have willingly perished by the peine forte et dure. In other angles were two other similar boxes, far less reverenced, indeed, but still greatly matters of awe. One of these was the pulpit of the ‘classical’ usher, one of the ‘English and mathematical.’ Interspersed about the room, crossing and re-crossing in endless irregularity, were innumerable benches and desks, black, ancient, and time-worn, piled desperately with much bethumbed books, and so beseamed with initial letters, names at full length, grotesque figures, and other multiplied efforts of the knife, as to have entirely lost what little of original form might have been their portion in days long departed. A huge bucket with water stood at one extremity of the room, and a clock of stupendous dimensions at the other.

Encompassed by the massy walls of this venerable academy, I passed, yet not in tedium or disgust, the years of the third lustrum of my life. The teeming brain of childhood requires no external world of incident to occupy or amuse it; and the apparently dismal monotony of a school was replete with more intense excitement than my riper youth has derived from luxury, or my full manhood from crime. Yet I must believe that my first mental development had in it much of the uncommon—even much of the outre. Upon mankind at large the events of very early existence rarely leave in mature age any definite impression. All is gray shadow—a weak and irregular remembrance—an indistinct regathering of feeble pleasures and phantasmagoric pains. With me this is not so. In childhood, I must have felt with the energy of a man what I now find stamped upon memory in lines as vivid, as deep, and as durable as the exergues of the Carthaginian medals.

Yet in fact—in the fact of the world’s view—how little was there to remember! The morning’s awakening, the nightly summons to bed; the conningş, the recitations; the periodical half-holidays, and perambulations; the play-ground, with its broils, its pastimes, its intrigues;—these, by a mental sorcery long forgotten, were made to involve a wilderness of sensation, a world of rich incident, an universe of varied emotion, of excitement, the most passionate and spirit-stirring. OA, le bon temps, que ce siècle de fer!’8

What do you think of this passage? Does not the character of this remarkable man begin to reveal itself? For my part, I feel that this picture of school life gives off a dark perfume. I sense the shiver of somber years of confinement running through it. Hours of imprisonment, the anxiety of a lonely and miserable childhood, fear of the master, our enemy, the hate of brutal comrades, the heart’s solitude, all these tortures of youth Edgar Poe somehow escapes. All those causes of melancholy fail to overcome him. Though young, he loves solitude, or rather he does not feel himself alone; he loves his own passions. The fertile mind of childhood makes everything agreeable, illuminates everything. Already it is clear that will power and solitary pride will play a great role in his life. Would you not say, indeed, that he is almost fond of suffering, that he has a presentiment of the inseparable companion of his future life, and that he seeks it with an eager desire, like a young gladiator? The poor child has neither father nor mother, but he is happy; he glories in being deeply stamped, like a Carthaginian medal.

Edgar Poe returned from Dr. Bransby’s school to Richmond in 1822, and continued his studies under the best teachers. He was then a young man quite remarkable for his physical prowess, grace and suppleness, and to the attractions of a strikingly handsome appearan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgement

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Part Four: Critical Miscellany

- Appendix:

- Notes