- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drawing of the Hand

About this book

According to expert instructor Joseph M. Henninger, the hand is not difficult to draw when its construction is well understood. In this guide for intermediate and advanced art students, Henninger devotes the first section to the anatomy of the hand and forearm. He also shares basic but seldom observed facts concerning comparative measurements. A helpful glossary provides Latin terms, English translations, and descriptions of the hand muscles' functions.

Drawings of the hand constitute the major portion of this volume, consisting mostly of adult male and female hands, followed by children's and babies' hands. The final section comprises a portfolio of drawings by Old Masters and contemporary artists, many accompanied by the author's insightful comments.

Drawings of the hand constitute the major portion of this volume, consisting mostly of adult male and female hands, followed by children's and babies' hands. The final section comprises a portfolio of drawings by Old Masters and contemporary artists, many accompanied by the author's insightful comments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drawing of the Hand by Joseph M. Henninger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PORTFOLIO OF DRAWINGS OF THE OLD AND MODERN MASTERS

SOMETIME during the years between 30,000 B.C. and 12,000 B.C. man made his first attempts to record the shape of his hand. According to the findings of Professor Hugo Obermaier, a world authority on the drawings of Ice Age man, these were the first graphic efforts of that period, preceding man’s drawings of the animals which cover the walls and ceilings of the Ice Age caves of France and Spain, (see Art in the Ice Age by Johannes Maringer and Hans-Georg Bandi, published by Fredrick A. Praeger, Inc. Library of Congress Catalogue card number: 52-13999).

By placing his hand or the hand of a friend against the dampened stone wall of the cave and then blowing a powder of iron oxide over it he left a negative silhouette or pattern of the hand on the wall. Two of the imprints show hands that have lost the two end phalanges of the fingers and the end phalange of the thumb. This could be, possibly, the first record of leprosy or ritualistic mutilation or maybe even the execution of early legal penalty.

The next recorded efforts to draw the hand, that remain to us, occur in the low relief decorations of the Assyrians and the paintings in the Egyptian tombs. Both the Assyrians and the Egyptians employed a stylistic approach in depicting the figure, namely, the head was shown in profile with the torso shown in front view and the legs again in profile. The hands and arms were always shown in actions that did not necessitate their being drawn in foreshortened views. The treatment of the hands was always a formalized formula, fingers were depicted as long and curvacious forms.

The Greeks were primarily devoted to sculpture in both the round and high relief. In the decoration of their magnificent vases and bowls they resorted to friezes of figures in various activities such as dancing, fighting and sports events coupled with running border designs of geometric pattern. In the drawings of the hands on these pieces of pottery the Greeks resorted to a stylized approach somewhat similar to that used by the Assyrians and the Egyptians.

In the mural paintings of India, done during the Gupta Period, 300 A.D., one finds drawings of hands that show considerable knowledge of physical structure and closely studied gesture. Hands are shown in foreshortened views and drawn most convincingly. There seem to be no actions of the hands that were avoided by their artists. Their painters took some liberties in drawing the figures, exaggerating the smallness of the waist, broadening the hips, enlarging the breasts and lengthening the eyes to conform with the Indian ideas of the ideal body. The hands, however, were drawn in normal proportion and with great grace. These paintings of the Gupta Period far surpassed in sophisticated draughtsmanship the works of artists working in Europe during the same era.

During the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages in Europe there was little or no effort by man to learn more about himself or the world in which he lived. The Church dominated his thinking and decreed that his thoughts should be devoted to the hereafter. It was more important to devote one’s thinking toward the reward of Heaven or the torture of everlasting damnation than to spend one’s efforts learning more about oneself and one’s world. In this atmosphere the arts stagnated. This curious era continued for about 800 years.

With the revival of learning there came into being that age which we refer to as “The Renaissance”. This well-known but loosely dated period was the strong hyphen between the Middle Ages and the era we call “Modern Civilization”. It was the spawning ground for emancipated humanistic thought. It is not the province of this book nor the desire of the author to delve deeply into the history or reasons why the Renaissance came into being — however, there are a few significant advances in thinking and achievement that are worthy of mention. Paper was introduced into Europe, a Chinese invention, that replaced parchment as a common working surface for both the authors and the artists. Moveable type and the printing press came into being to replace the hand copied books made by monks in abbeys. The mariner’s compass expanded navigation — gunpowder, another Chinese invention, revolutionized the “art” of war. The Ptolemaic concept of astronomy was replaced by the Copernican theory. The writings of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio were original, monumental, works of art. It was in fact the works of these authors that did most to free the graphic artist of the day.

In this rich soil of intellectual inquiry all the arts flourished, none more so than the art of painting and drawing. By some peculiar fortuitous circumstance there appeared, virtually simultaneously, a group of artistic giants, Michelangelo, da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, Bellini, del Sarto, Giorgione and on and on. The geometry of sight, which we call perspective, was discovered and perfected. The popes and cardinals of the church, coming from the ruling houses of Rome and Florence, were champions of the new humanist thought. Artists could now study the anatomy of man without fear of suffering the wrath of the Church. Men began to draw from the posture of knowledge instead of simple visual observation of surface. Drawings showed a new vigorous authority. The seed of man’s inquisitiveness broke into bloom during this period and bore the fruit that produced Modern Man. The author suggests that those students who have not been exposed to the history of the Renaissance would profit greatly by devoting time to its study.

WASHINGTON ALLSTON 1779-1843

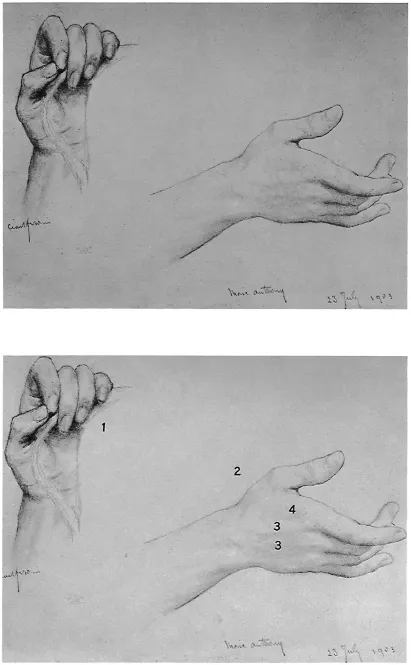

Allston was born in South Carolina in 1779, was educated at Harvard and spent most of his life in Boston. He traveled abroad during 1803 and 1806 to London and Paris. Living two years in London and a year in Paris, he attempted to broaden his education and training as an artist. From Paris, in 1806, he went to Italy, where he became enamored of Venetian painting. Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto were among those he especially admired. Before his return to America, Allston’s paintings were large, subjective canvases, romantic visions of nature and life. Through it all, however, the influence of classical art can be observed. In his work, Allston reveals the awe-inspiring grandeur of nature, and he was one of the first American artists to be so influenced. It was after 1818 that his work began to reveal a lyrical dreamlike quality. Also, at this time, his work took on a much smaller scale. Allston, it can be said, set new standards for American painting, and thus he stands out in the history of its development.

It will be noted that Allston in his development of the form in this drawing used modeling that went across the form. Note the strokes of the crayon at (1) which give the feeling of the volume of the form.

Charcoal heightened with White Chalk

FOGG ART MUSEUM, HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MASS. WASHINGTON ALLSTON TRUST

FOGG ART MUSEUM, HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MASS. WASHINGTON ALLSTON TRUST

SIR LAURENCE ALMA-TADEMA (1836-1912)

Alma-Tadema was born in the Netherlands. He entered the Antwerp Academy at the age of sixteen and studied under Gustav Wappers and Baron Henri Leys. He was a precocious student and became Baron Leys’ assistant in painting the murals in the Antwerp City Hall in 1859. He won the Gold Medal for painting in Amsterdam at the age of twenty six. His most characteristic work was in the area of scenes from Greek and Roman subject matter. In 1870 he went to live in England, where he enjoyed great success. In 1876 he was elected associate of the Royal Academecian. Queen Victoria knighted him in 1899. His works were remarkable for the realistic rendering of naturalistic textures. He died in London in June, 1912.

In these drawings Alma-Tadema has contented himself with naturalistic value pattern in drawing No. 1. Both of these drawings were made to be used as models to paint from. One can see that drawing No. 2 is labeled “Marc Antony”, obviously intended for a painting dealing with Roman subject matter. In drawing No. 2, great care has been taken to record the outline of the hand and fingers. The modeling in the back of the hand has been subtly drawn to indicate tendons of the fingers (3) and the first interosseus (4).

Pencil

THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, ENGLAND

THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, ENGLAND

ANTOINE WATTEAU (1684-1721)

This charming French painter was born to humble Flemish parents. At fourteen years of age he became the apprentice of a mediocre painter, Gérin of Valenciennes. When Gérin died, Watteau was left penniless; he went to Paris to work for a scene-painter, Métayer. Watteau, whose health was never robust, worked in a factory that turned out religious paintings wholesale. For this he was paid three francs a week and meager food. In 1709 he won second place in the Prix de Rome competition. Watteau was elected associate of the Academy in 1712 and full member in 1717. His diploma painting, The Embarkmeni for Cythera now hangs in the Louvre. Watteau was invited to live in the household of Crozat, the greatest private art collector of his time. While a guest of Crozat, Watteau painted four decorative panels of The Seasons for his benefactor. For six months he li...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Author’s Notes

- Anatomy

- Action Studies of the Hand

- Preliminary Drawings & Sketches

- Portfolio of Drawings of the Old and Modern Masters