- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History and Art of Personal Combat

About this book

A comprehensive history of classical and historical swordsmanship, this volume details uses of the broadsword, two-hander, and rapier as well as the dagger, bayonet, and halberd. Vintage engravings, line art, photographs, and other illustrations grace nearly every page and the author touches on other types of modern weapons, including rifles and handguns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The History and Art of Personal Combat by Arthur Wise in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

IN THE BEGINNING: EARLY ATTITUDES

Understandably, the early years of personal combat are not well documented. Not until the European Renaissance, it seems, was a man able to wield both a sword and a pen – men like Lebkommer, Sainct Didier and Marozzo. Nevertheless, we have some evidence of the weapons used by earlier men and there is visual evidence in art. There is, too, the evidence of historians, raconteurs and poets who witnessed the exploits of violent men. And there is another technique we can employ; we can build replicas of early weapons. If we have had any experience in the handling of weapons in general, then these replicas will give us some additional insight into the nature of the originals, and the way in which they might have been used.

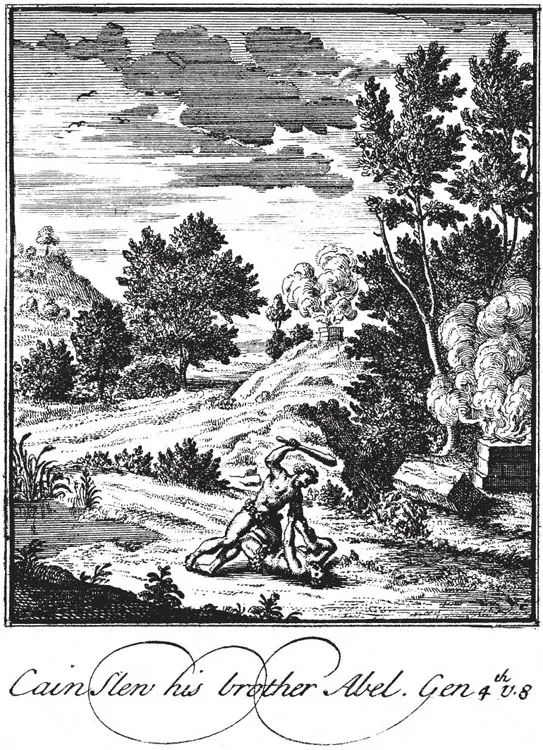

The story of Cain and Abel highlights at least some of the recognised features of personal violence. These features are relevant to personal combat, though Cain’s attack on his brother can hardly in itself be regarded as combat:

‘And in process of time it came to pass, that Cain brought of the fruit of the ground an offering unto the Lord.

‘And Abel, he also brought of the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof. And the Lord had respect unto Abel and to his offering:

‘But unto Cain and to his offering he had not respect. And Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell.

‘And the Lord said unto Cain, Why art thou wroth? and why is thy countenance fallen?

‘If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin coucheth at the door: and unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him.

‘And Cain told Abel his brother. And it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him.

‘And the Lord said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: am I my brother’s keeper?

‘And he said, What hast thou done? the voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground.

‘And now cursed art thou from the ground, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother’s blood from thy hand;

‘When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength; a fugitive and a wanderer shalt thou be in the earth.

‘And Cain said unto the Lord, My punishment is greater than I can bear.’*

The story reveals an attitude which sees personal violence as a challenge to the natural order of things. It is a challenge, too, to authority – in this case, the authority of God. It is not so much that Cain has inflicted death on his brother, since death would have come to Abel inevitably, in the natural course of time. It is that he has overstepped the terms of his office as a human being. The gift of life and death is not in the hands of man, but in the hands of a higher authority. Despite the fact that man has it in his power to inflict death on another, it is a power he exercises at his peril. The fact that Cain appears to be motivated by the very human feelings of bitter disappointment and jealousy in no way diminishes his crime or his punishment. He has killed without the sanction of a higher authority, and he must suffer the severest punishment for it.

This attitude of authority to individual violence is one which has accompanied personal combat throughout human history:

‘They that have power to hurt and will do

none . . .

They rightly do inherit heaven’s graces.’

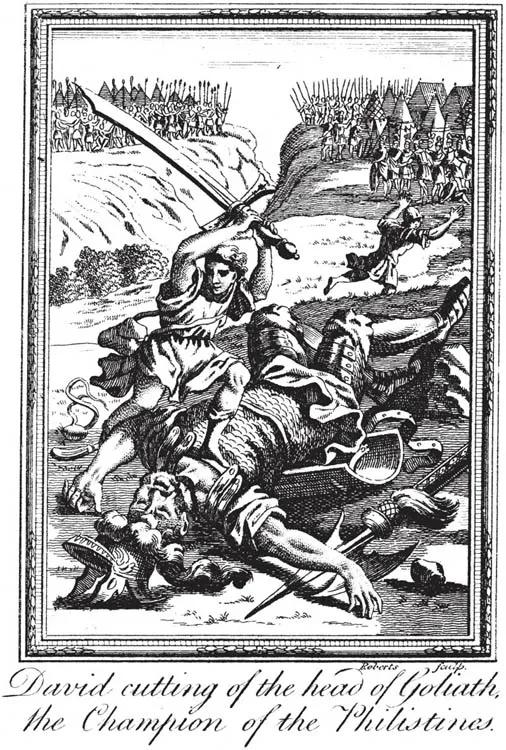

But there is another attitude, apparent in the David and Goliath story:

‘And there went out a champion out of the camp of the Philistines, named Goliath, of Gath, whose height was six cubits and a span.

‘And he had an helmet of brass upon his head, and he was clad with a coat of mail; and the weight of the coat was five thousand shekels of brass.

‘And he had greaves of brass upon his legs, and a javelin of brass between his shoulders.

‘And the staff of his spear was like a weaver’s beam; and his spear’s head weighed six hundred shekels of iron: and his shield-bearer went before him.

‘And he stood and cried unto the armies of Israel, and said unto them, Why are ye come out to set your battle in array? am not I a Philistine, and ye servants to Saul? choose you a man for you, and let him come down to me.

‘If he be able to fight with me, and kill me, then will we be your servants: but if I prevail against him, and kill him, then shall ye be our servants, and serve us.

‘And the Philistine said, I defy the armies of Israel this day; give me a man, that we may fight together. . . .

‘And David said, The Lord that delivered me out of the paw of the lion, and out of the paw of the bear, he will deliver me out of the hand of this Philistine. And Saul said unto David, Go, and the Lord shall be with thee. . . .

‘And the Philistine said to David, Come to me, and I will give thy flesh unto the fowls of the air, and to the beasts of the field.

‘Then said David to the Philistine, Thou comest to me with a sword, and with a spear, and with a javelin: but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, which thou hast defied. . . .

‘And it came to pass, when the Philistine arose, and came and drew nigh to meet David, that David hastened, and ran toward the army to meet the Philistine.

‘And David put his hand in his bag, and took thence a stone, and slang it, and smote the Philistine in his forehead; and the stone sank into his forehead, and he fell upon his face to the earth.

‘So David prevailed over the Philistine with a sling and with a stone, and smote the Philistine, and slew him; but there was no sword in the hand of David.

‘Then David ran, and stood over the Philistine, and took his sword, and drew it out of the sheath thereof, and slew him, and cut off his head therewith.’*

The attitude behind the story is clearly one of approval. The slaying of Goliath by the young David is an example of how a young man, motivated by the highest ideals and beliefs, was expected to behave in such circumstances. Yet the result of the contest is the same as the attack by Cain on Abel. Goliath lies dead, just as Abel did. The approval in one case and condemnation in the other, lies not in the result but in the circumstances. David is not killing on his own behalf. He is an instrument of authority. He kills with the permission of Saul and with the support of the God of Israel. Cain’s action is an assertion of his own individuality; as such it is inadmissible. David’s action is on behalf of his king and his society; as such it is not only admissible but praiseworthy. These two attitudes to personal violence have been with us whenever one man has met another, bent on doing him physical injury. It seems that where combat is engaged in to further personal ends, it is socially deplored. Conversely, where it takes place under some impersonal banner – God, or the State – it can be admissible. The modern concept of push-button warfare is the logical outcome of these attitudes.

Goliath, as we have seen, was equipped ‘with a sword, and with a spear, and with a javelin’, and these are weapons typical of a long historical period. The Assyrians and Babylonians, the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans were all similarly equipped. Preceding them, archaeological evidence shows the existence of similar pointed weapons with blades of flint and other stones. A spear could be produced by lashing a stone to the end of a wooden staff. A knife could be made by binding one end of a long stone with leather, and chipping the other end into some semblance of a blade. Both were suitable for hunting, and no doubt both were used for combat. Bone and horn were as effective as chipped stone for producing a weapon capable of penetrating flesh. Knives, spears and arrows could be produced from them. Even earlier must have been the discovery that sharpened wood, hardened by fire, could effectively be used as a weapon.

From such weapons arises the idea of penetration of the body of an enemy, as a means of destroying him. But even earlier must have been the discovery of the susceptibility of a body to heavy blows, the idea not of penetration with a point but of crushing or cutting – an idea that produced the club and the first crude axes. Both these ideas – of penetration and crushing – run side by side through the history of personal combat.

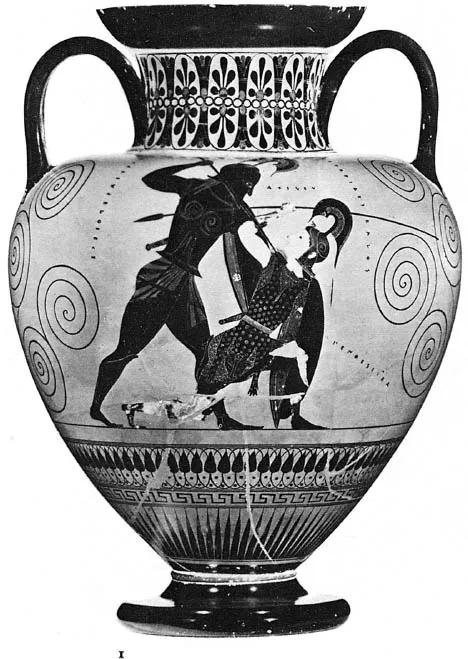

And there is a third idea, that of defence. Goliath had his shield-bearer ‘that went before him’, and ‘he had an helmet of brass upon his head, and he was clad with a coat of mail . . . and he had greaves of brass upon his legs’. The purpose of all this defensive equipment was to place it between his otherwise defenceless body and his opponent’s weapon. By contrast, David carried no defensive equipment. His only technique of defence was to make sure that no blow fell on him, by getting out of the way of it. He would defend himself when necessary by avoiding his opponent’s weapon. So we see in the dawn of history the two principles of personal combat – each subdivided – already established: the principle of attack, either by stabbing or crushing, and the principle of defence, either by interposing some object between the attacker’s weapon and one’s own body or by dodging the attacker’s weapon.

These principles are apparent in the murderous activities of Achilles before Troy. His fighting technique relied on great speed of movement, uncontrolled aggression and tremendous physical strength. The same qualities are present – together with the principles of attack and defence – in his fight with Hector:

‘With this Achilles poised and hurled his long-shadowed spear. But illustrious Hector was looking out and managed to avoid it. He crouched, with his eye on the weapon; and it flew over his head and stuck in the ground. But Pallas Athene snatched it up and brought it back to Achilles.

1 Achilles slaying Penthesilea the Queen of the Amazons. From a vase of 540–530 BC in the British Museum.

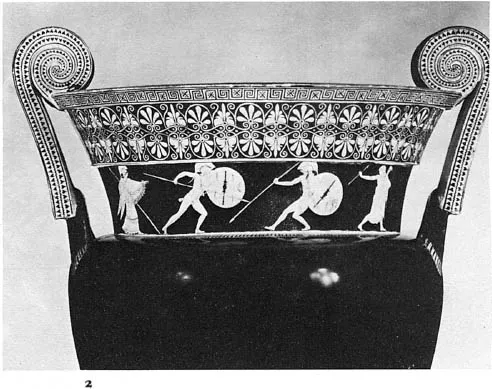

2 The fight between Achilles and Hector. From a vase illustration of about 490 BC in the British Museum.

‘Hector the great captain, who had not seen this move, called across to the peerless son of Peleus: “A miss for the god-like Achilles! It seems that Zeus gave you the wrong date for my death! You were too cocksure. But then you’re so glib, so clever with your tongue – trying to frighten me and drain me of my strength. Nevertheless, you will not make me run, or catch me in the back with your spear. Drive it through my breast as I charge – if you get the chance. But first you will have to dodge this one of mine. And Heaven grant that all its bronze may be buried in your flesh! This war would be an easier business for the Trojans, if you, their greatest scourge, were dead.”

‘With that he swung up his long-shadowed spear and cast. And sure enough he hit the centre of Achilles’ shield, but his spear rebounded from it. Hector was angry at having made so fine a throw for nothing, and he stood there discomfited, for he had no second lance. He shouted aloud to Deiphobus of the white shield, asking him for a long spear. But Deiphobus was nowhere near him; and Hector, realising what had happened, cried: “Alas! So the gods did beckon me to my death! I thought the good Deiphobus was at my side; but he is in the town, and Athene has fooled me. Death is no longer far away; he is staring me in the face and there is no escaping him. Zeus and his Archer Son must long have been resolved on this, for all their goodwill and the help they gave me. So now I meet my doom. Let me at least sell my life dearly and have a not inglorious end, after some feat of arms that shall come to the ears of generations still unborn.”

‘Hanging down at his side, Hector had a sharp, long and weighty sword. He drew this now, braced himself, and swooped like a high-flying eagle that drops to earth through the black clouds to pounce on a tender lamb or a crouching hare. Thus Hector charged, brandishing his sharp sword. Achilles sprang to meet him, inflamed with savage passion. He kept his front covered with his decorated shield; his glittering helmet with its four plates swayed as he moved his head and made the splendid golden plumes that Hephaestus had lavished on the crest dance round the top; and bright as the loveliest jewel in the sky, the Evening Star when he comes out at nightfall with the rest, the sharp point scintillated on the spear he balanced in his right hand, intent on killing Hector, and searching him for the likeliest place to reach his flesh.

‘Achilles saw that Hector’s body was completely covered by the fine bronze armour he had taken from the great Patroclus when he killed him, except for an opening at the gullet where the collar bones lead over from the shoulders to the neck, the easiest place to kill a man. As Hector charged him, Prince Achilles drove at this spot with his lance; and the point went right through the tender flesh of Hector’s neck, though the heavy bronze head did not cut his windpipe, and left him able to address his conqueror. Hector came down in the dust and the great Achilles triumphed over him. “Hector,” he said, “no doubt you fancied as you stripped Patroclus that you would be safe. You never thought of me: I was too far away. You were a fool. Down by the hollow ships there was a man far better than Patroclus in reserve, the man who has brought you low. So now the dogs and birds of prey are going to maul and mangle you, while we Achaeans hold Patroclus’ funeral.”

‘“I beseech you,” said Hector of the glittering helmet in a failing voice, “by your knees, by your own life and by your parents, not to throw my body to the dogs at the Achaean ships, but to take a ransom for me. My father and my lady mother will pay you bronze and gold in plenty. Give up my body to be taken home, so that the Trojans and their wives may honour me in death with the ritual of fire.”

‘The swift Achilles scowled at him. “You cur,” he said, “don’t talk to me of knees or name my parents in your prayers. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One: In the Beginning: Early Attitudes

- Chapter Two: The Individualists

- Chapter Three: The Ascendancy of the Sword

- Chapter Four: Cut or Thrust?

- Chapter Five: The Supremacy of the Point

- Chapter Six: Transition

- Chapter Seven: The Perfection of Theory and Practice

- Chapter Eight: The Decline of the Sword

- Chapter Nine: Gun Fighters

- Chapter Ten: Other Ways to Kill a Man

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index