![]()

1

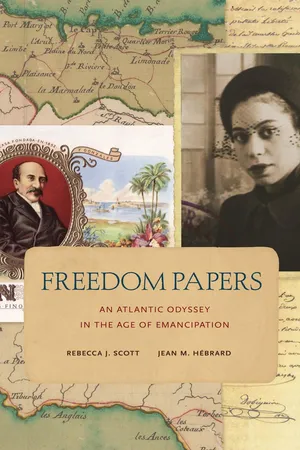

“Rosalie, Black Woman of the Poulard Nation”

When Édouard Tinchant, writing to General Máximo Gómez in 1899, referred to himself as “of Haïtian descent,” he linked his own history to the era during which his parents had felt the shock waves of three great revolutions—those that gave rise to the United States of America, the French Republic, and the nation of Haiti. When he spoke of himself as a “son of Africa,” he further signaled his ancestors’ place among those in the Caribbean whose status was that of slaves, or whose status balanced precariously somewhere between slavery and freedom.1

For a number of the African men and women brought as captives to the Caribbean, these had not been the first revolutions that they had encountered. In the valley of the Senegal River in West Africa, in the region called Fuuta Tooro, a sector of the Islamic clerical elite led a movement that overturned the warrior aristocracy in the mid-1770s and forced into public debate the question of the legitimacy of selling fellow Muslims to Europeans as slaves. The Almamy (or imam) who ruled Fuuta Tooro after that revolution obliged the French to sign a treaty in which they agreed to refrain from transporting any of his subjects into the trade. Neighbors and rivals who refused the authority of the Almamy nonetheless continued to raid into his territory and seize captives to be sold for deportation to the Americas.2

The people of Fuuta Tooro, along with others who spoke the Pulaar language, were referred to by the French as the “Foules” or the “Poules,” terms that in the Americas were often rendered as “Poulard.” When a young woman being held as a slave in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue was referred to as “Rosalie, négresse de nation Poulard,” it was thus an origin in Senegambia that was implied. The paper trail linking Édouard Tinchant to this woman called Rosalie involves two documents, each brought into being in a moment of struggle, and later deposited with local officials in an effort to secure a fragile status.

In order to prove that she could by rights adopt her father’s surname, despite having been born out of wedlock, Édouard Tinchant’s mother Élisabeth Dieudonné went to a public notary in New Orleans in 1835 with a copy of her baptismal record. According to this document, she had been born in 1799 in the colony of Saint-Domingue, in the midst of the Haitian Revolution. A free black woman named Marie Françoise, called Rosalie, was Élisabeth’s mother. A Frenchman named Michel Vincent acknowledged in the baptismal act that he was Élisabeth’s father. Having examined the document, the New Orleans notary authorized Élisabeth to take on the surname Vincent, and, as was standard practice, he saved a copy of the act in his bound volume of notarized records for the year.3

The names of Michel Vincent and Rosalie appear a second time in documents that they deposited in 1804 with French officials in Santiago, Cuba. They had fled to Cuba not as a result of the uprising of slaves in the northern plain of Saint-Domingue in 1791, but instead to escape the warfare that engulfed the countryside in 1802 when Napoléon Bonaparte sent a French expeditionary force to try to destroy the power of the black and brown generals who ruled the colony in the name of France, first among them Toussaint Louverture. Michel and Rosalie carried with them in their flight a set of freedom papers that identified her more fully as “Marie Françoise, dite Rosalie, négresse de nation Poulard”—Marie Françoise, called Rosalie, black woman of the Poulard nation. Together these documents confirm that Édouard Tinchant’s grandmother Rosalie was a survivor of captivity, enslavement, and the Middle Passage from West Africa to the Caribbean.4

The words “of the Poulard nation” are suggestive, but they are not geographically or chronologically precise. As ship captains made their purchases on the coast of Senegambia, they rarely categorized individual captives with any precision. For the buyer and the seller in a West African port, the exchange of captives for goods was usually characterized by a generic phrase like “captifs jeunes pièces d’Inde sans aucun défaut” (young captives pièces d’Inde without any flaws). Pièce d’Inde was a unit based on the exchange value of a bolt of printed cloth from India, the cost of a healthy male captive between the ages of fourteen and thirty-five. Individual names and ethnic affiliations generally went unrecorded.5

It was instead on arrival in the Antilles that ship captains began to vaunt the “nationalities” of those whom they would sell. The ship La Valeur, for example, left the French port of Nantes on June 22, 1786, for Saint-Louis du Sénégal, where in February it loaded some seventy-four captives. Two months later, the Affiches Américaines described the cargo of La Valeur offered for sale in the port of Cap-Français, Saint-Domingue, as “a handsome load of blacks of the Yolof, Poulard, and Bambara nations.”6

In some cases, such “national” markers were simply a rough-and-ready indicator of the African ports of call of a slaving vessel. The word “Sénégal,” for example, was often used to refer generically to those purchased in the port of Saint-Louis du Sénégal, near the mouth of the Senegal River. But in many cases sellers used a label that attributed not simply a place of acquisition but a place of origin, designating a people by reference to a region, a language group, or a political entity. This system of designation rested on a flexible and to some extent imaginary European geography of Africa, one that assigned specific characteristics to particular groups, who were in turn associated with loosely defined places. Ship captains and traders often drew on these associations to describe Africans in terms that might evoke favorable images of skills, robustness, strength, beauty, or tractability. The colonist Moreau de Saint-Méry, for example, waxed enthusiastic about captives he referred to broadly as “Senegalese,” evoking both the port of Saint-Louis du Sénégal and the valley of the Senegal River more broadly. They were “superior” slaves, he wrote, “intelligent, good, faithful, even in love, grateful, excellent domestic servants.”7

Moreau de Saint-Méry identified a closely related set of captives with the term “Poulard,” a word that he viewed as a popular deformation of the proper noun “Foule.” The term “Foule,” derived from the vernacular “Pullo” (plural: Fulbe), was used by French-speaking traders, administrators, and explorers to refer to a people, many of them cattle herders, often living in the middle valley of the Senegal River. Moreau distinguished the Foules, for example, from the Jolof (his term was “Yoloffes”) who dominated the lower valley as well as much of the inland and coastal area farther to the south.8

Although in theory derived from places of origin, these designations also reflected conventional slaveholder wisdom about appearance: Moreau and others believed the Poulard to be characteristically tall, thin, and “copper-colored.”9 Ethnographers and historians have adopted a broader usage of the modern terms “Peul,” “Fulani,” or “Fulbe,” distinguishing among many now far-dispersed populations who may speak variants of the language called Pulaar. Scholars generally eschew the attribution of timeless cultural attributes and specific physical features to the group, concentrating instead on the linguistic, cultural, and economic variability among those who migrated at different moments, and on the transformations that took place as they came into contact with other groups.10

For the eighteenth-century traders and planters who assigned “nations” to those in the human cargoes they sought to sell or buy, however, these subtleties were rarely to be seen. In Saint-Domingue the label “Poulard” seems simply to have carried a positive tone, signifying a group in which the men were expected to be good at handling animals, and the women characterized by domestic skills and beauty. For those thus labeled, of course, it might also correspond to some degree of shared history and language.11

Although a significant proportion of the captives during the very early years of the trade to Saint-Domingue had come from Senegambia, by the end of the eighteenth century most came from farther south in Africa. Even among the men and women who were from Senegambia, those denominated Poulard were outweighed by others designated Bambara, Sénégal, Soso, and Mandingo. The relative uncommonness of the designation “Poulard” makes it likely that when variants of the phrase “Rosalie de nation Poulard” were used in records from the district of Jérémie in Saint-Domingue to identify a relatively young woman, they do indeed refer to the same person.12

The designation “of the Poulard nation” may have been reinforced by Rosalie herself. To call oneself a member of the Poulard nation could, by the end of the eighteenth century, be a politically resonant act. The French who controlled the island of Saint-Louis du Sénégal were locked in conflict with a new régime in the middle valley whose policies posed obstacles to the deportation of Muslim captives for the Atlantic trade. Word had reached metropolitan France and England that there was a polity among the Poules now ruled by a man called the Almamy, who claimed the right to block the passage of slave traders through his territory. The English antislavery activist Thomas Clarkson, after interviewing a French botanist who had traveled in the region, wrote in praise of what he saw as the Almamy’s forthright actions against the trade, contrasting them with the hesitations of European rulers.13

One French adventurer, M. Saugnier, who had abandoned the life of a grocer to try his luck as a trader in Africa, provided a meticulous account of his voyage along the Senegal River in 1785—almost an advertisement to those who might wish to follow in his footsteps. Describing the nation of the Poules as extending from below the town of Podor upriver to Matam, a fortified village occupied by both Poules and Saltinguets, Saugnier gave his readers a bitter description that reflected his own frustration as a slave trader with the uncooperativeness of their leaders, particularly the cleric named Abdulkaadir Kan: “Although the Poule nation lives in one of the most beautiful parts of Africa, it is however a very miserable one.… They are ruled by a chief of their religion—a miserable mixture of Mohammedism and Paganism—called the Almamy.”14

Abdulkaadir Kan was a highly educated Muslim leader who had joined a movement denouncing religious laxity and the prevalence of slaving raids that took captive even the dependents of the most respected clerics. After victory in what would come to be known as the Revolution of the Toorobe, Abdulkaadir Kan took on the title of the Almamy and ruled over the area designated Fuuta Tooro, extending many hundreds of miles along the river and across the narrow band of rich lands on either side.15 The subjects of the Almamy generally spoke or learned to speak the Pulaar language, and those who were not already Muslims converted to Islam. For the French traders and administrators on the island of Saint-Louis these people—on whom they depended both for food supplies and safe passage on the river—would be known as the “Nègres Poules du pays de Toro” (Poulard blacks of the land of Tooro), or simply as the Poules.16

Historically, the people of the middle valley had long participated in raids and battles in which they took captives, who in turn could either be ransomed by their communities of origin, or sold into the domestic, the trans-Saharan, or the Atlantic trade. The Almamy introduced a new policy, based on a more demanding reading of the Qur’an, and prohibited the selling of fellow Muslims into the Atlantic trade. Although domestic slavery continued to be practiced within his realm, by 1785 he was able to impose a treaty on the French that prohibited them from acquiring captives from his domain. The Almamy’s control of a key segment of the river enabled him to inspect convoys, and he would not allow captives he judged to be his subjects to be sold to the traders on the island of Saint-Louis who supplied the European slavers. Given the difficulties of navigating the river, and the vulnerability of the convoy during the long voyage, traders had little choice but to observe the ban.17

After Abdulkaadir Kan’s ascent to power it became less likely that the inhabitants of Fuuta Tooro would be transported to the Americas as slaves. There were, however, various paths to captivity, even during the time of the treaty between the Almamy and the French. Reversals in the Almamy’s wars of expansion put captives in the hands of his neighbors; his rivals did not hesitate to attempt incursions into his territory; and he himself could use sale as a means of internal control. Armed groups of various kinds raided into Fuuta for captives, aiming to sell them to the Europeans at Saint-Louis, Gorée, or elsewhere. If not ransomed in time, Pulaar-speaking men and women among these captives would thus end up in the long-distance slave trade.18

The trader Saugnier provided his French readers with a picture of a sequence of events that could lead to such captivity. Describing the people he called the Saltinguets, the author wrote:

They are commanded by a prince who by right of birth should have been the king of the Poules; but the priests who despoiled him chased him out of his land. This prince is courageous and makes frequent incursions into the lands of the Poules, and sells all of his captives to his neighbors the Moors, who take them to [Saint-Louis du] Sénégal.19

In effect, the Almamy’s protection was effective only where and when he could impose his will, and there were plenty of competitors eager to circumvent his scruples on seeing his ...