![]()

1

Worlds Apart

Ann woke to a hard and persistent knock on her bedroom door. After staying in bed as long as possible, she wrapped herself into a thick bathrobe, put on warm socks, and stumbled to the bathroom to brush her teeth. She didn’t say “good morning” to her father and didn’t expect any form of greeting from him, either. If she hadn’t pushed him grumpily away from the basin to reach the faucet, one would have thought that neither was aware of the other. It was a school morning, shortly before the Christmas break. Ann was, as usual, far behind schedule and, like her father, Jim, began the new day in a state of semi-consciousness. Before Jim had school-aged children he used soap and a razor, which he thought produced a much cleaner shave, but now that he was forced into this early routine, he tolerated the noise of an electric razor, having cut himself too often. His wife, Helen, was already downstairs making breakfast together with their son, Toby.

In contrast to father and daughter, who went about their morning routines in silence, Toby and his mother were chatting with each other like a pair of canaries. Toby was telling her about his field trip to the dinosaur exhibit and got quite carried away when enumerating the different raptors he had seen. While his mother was preparing sandwiches for the children’s school breaks, Toby set the table, but soon got distracted by the back of the cereal box, which he had just placed in front of his bowl. He read all about the new dinosaur collection that would be coming out next year—one in each package. He decided to eat more cornflakes in the future, at least two bowls every morning.

Helen always put extra effort into the sandwiches for her firstborn. She wanted to make sure that her daughter would eat them because she usually left the house with nothing more than a cup of tea in her stomach. By the time Ann had crossed the threshold into puberty, she had stopped eating anything before leaving the house, and Helen had fought—and lost—endless battles about “proper breakfasts.” It was actually Jim who had put an end to this struggle: “Make her a good sandwich with her favorite stuff on it and she will eat it in school as soon as she is hungry.” Of course, no parent can ever be sure what really happens to lunches from home, but the fact that Ann uttered requests from time to time for variations in the narrow theme of her favorite foods encouraged Helen.

At around seven o’clock Jim joined the talkative pair, kissed Toby on his way through the kitchen and then Helen, who handed him a big mug of coffee. The three sat down at the breakfast table, and Helen, as usual, yelled, “Hurry up, Ann, the bus will be here in twenty minutes!” They were lucky because the bus stop was right in front of their house, and Ann made the best of this short distance by coming downstairs only a couple of minutes before it arrived. Helen’s primordial cry was a remnant of her “proper breakfasts” fight.

At last, Ann did join the others, slowly sitting down at the table to sip her tea. Toby continued his lively dinosaurial narrative, mainly addressing his mother. He only approached his sister at breakfast if he was in a mischievous mood. She was an easy victim, unable to muster resistance, although later in the day she usually did get her revenge. Helen was half listening to Toby and half concentrating on planning the day, making her to-do list, and giving Jim or Ann short instructions. The chances that Helen could have a real conversation with her husband in the morning were greater in summer, when daylight flooded the kitchen and they occasionally had breakfast on the terrace. Now that the sun came up after the children were in school, all of them were more subdued than usual—even Toby and his mother. Helen was thinking of the PTA meeting scheduled for that evening and decided to ask Jim to go—he was much more up to it at that time of day, and she could go to bed early.

Ann brooded about the school day ahead of her. Why math in the first period? Why not art or history? She was actually quite good at math, but she needed at least half a functioning brain to solve mathematical problems, and most of her brain certainly didn’t wake up before ten o’clock or even later, no matter how early or late she got up. When Ann left the room to get her coat, Jim was able to produce the first smile of the day when he read the back of his daughter’s tee shirt: “Early to rise and early to bed makes a bird healthy, wealthy, and dead.”1

This first case represents—with minor variations—the morning routine of millions of households across the globe. In that sense, it is almost trivial. But apparent trivialities will play an important role in this book. How easily do we wake up in the morning, and why? Jim, Helen, Ann, and Toby seem to be worlds apart at this early hour: Helen and Toby feel fresh, and Jim and Ann feel woolly. The case is rich in information that you might have absorbed without even noticing, but it also triggers many questions: Is this a sex or gender issue?2 Does age play a role? Does the ability to wake up depend on the time of day? Are different wake-up types also different fall-asleep types? What do eating habits have to do with these different wake-up types? Does performance in such different activities as math and art depend on the time of day? The wake-up type? Some of these questions can be answered by the story itself.

Jim, Helen, Ann, and Toby’s morning touches upon many different aspects of temporal life and biological clocks. We are told when the story takes place (an early weekday morning shortly before Christmas), but we need to know where the family lives. Our conclusions will differ radically if the family lives in South Africa, Peru, or Australia rather than Europe, Japan, or the United States. But the story gives several hints to indicate that the family lives somewhere in North America or northern Europe: if it is nearly Christmas and dark outside, the family must live in the northern hemisphere. The size of the house and family and what they eat may provide other hints.

It would also be helpful to know the approximate ages of the family members. Let’s start with an educated guess: Toby appears to be younger than Ann, and Jim is probably older than Helen. Toby must be about six or seven because he is still young enough to be fascinated by dinosaurs but old enough to read the back of the cereal box. Ann, firstborn, has entered puberty but still lives at home, so let’s put her at fourteen.3 Helen and Jim, their parents, therefore might be in their early forties. Theoretically, Helen could be much younger and Jim much older, but that is somewhat beside the point.

Now let’s turn to the central theme—the different wake-up types. Father and daughter are not exactly communicative. Is Ann mad at her father or does her grumpy behavior merely reflect her resentment of having to get up at that ungodly hour? We could ask the same questions about Jim. By contrast, Helen and Toby are in the best of moods, already fully awake and active. Is this just the normal contrast between teenagers and children, or could these behavioral differences be—at least partly—accounted for by different wake-up types? Being a certain wake-up type is obviously not a simple matter of age, sex, or gender since both Helen and Toby are more awake than either Jim or Ann.

Once again, the story answers our questions. Before Jim had children at school, he felt vigilant enough to give himself a clean shave. Ann is apparently quite good at math after ten o’clock. Different wake-up types are apparently also different fall-asleep types. Helen is fresh in the morning but feels sleepy quite early in the evening. Although Jim has to get up on weekdays at approximately the same time as Helen does, he is dead tired in the morning but still quite alert in the evening—the PTA meeting will, therefore, be his task.

We know from experience—starting in our own families—that individuals possess different timing types, or chronotypes.4 In many cultures and languages, chronotypes are often named after birds—early birds and late birds.5 The common usage of larks and owls suggests that we are dealing with two categories. A Danish researcher has recently coined them, less poetically, A and B types, supporting the notion of two categories. However, the attempt to categorize any population of living beings into two categories is rarely correct. In general, human qualities, including chronotype, almost never fall strictly into two simple categories.

My colleagues and I have investigated human chronotypes for many years by asking thousands of people about their sleep habits with the help of a questionnaire.6 We use the answers to these questions to define a person’s chronotype. Defining the timing of an event is not necessarily straightforward. “When did you hear the shot?”; “When is high tide?”; or “When did the sun rise?” are easy questions because they concern clearly definable events. “When do you usually sleep?” is more complicated because we usually sleep for seven to eight hours. We therefore ask “When do you usually fall asleep?” or “When do you usually wake up?” But the answers to even these questions are difficult to translate into a person’s chronotype. Let’s suppose that Person A sleeps from 10 P.M. to 6 A.M., Person B from 10 P.M. to 8 A.M., and Person C from midnight to 6 A.M. If chronotype were defined by sleep onset, A and B would be the same type. If one defined it by sleep end, A and C would fall into the same category. The difficulty arises because sleep has (at least) two different and independent qualities: sleep timing and sleep duration.

It turns out that the midpoint of sleep is best for defining a person’s chronotype and also solves the problems described above. The calculation of midsleep is easy: if a person usually falls asleep at midnight and usually wakes up at eight, then his usual midsleep is 4 A.M. All these sleep times should represent what is done daily, not what is the exception, such as a party or a late night at work. Midsleep of Person A would be 2 A.M., that of Person B would be an hour later at 3 A.M., and Person C would have the same midsleep as B but would sleep four fewer hours, going to bed two hours later and waking up two hours earlier.

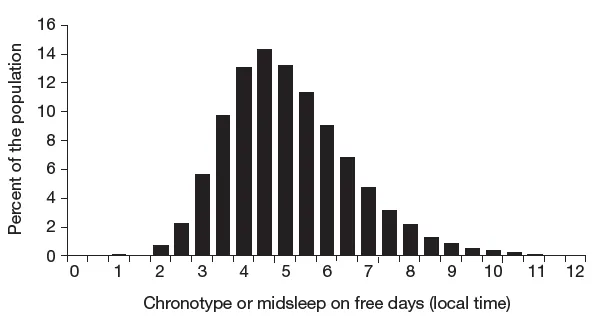

Our large database allows us to investigate the epidemiology of sleep behavior in different populations worldwide.7 The figure shows the distribution of midsleep in Central Europe (containing the answers from approximately 100,000 participants, predominantly Germans).8 The distribution is almost a perfect bell shape, although late types are slightly more numerous than early types.9 Categories like larks and owls, A and B people, misrepresent the continuous distribution of chronotypes as much as dwarves and giants misrepresent the distribution of body height. These opposites simply label the extreme types at both ends of distributions, which are extremely rare.

We base the first assessment of an individual’s chronotype on her sleep behavior on free days, when it is not dominated by work or school times but rather by individual preference, by a body clock that dictates her internal time. Slightly over 14 percent of the population (represented by our database) fall into a midsleep category of 4:30 to 5:00 A.M. Presuming a sleep duration of eight hours (to make things simple), individuals in this category go to bed on free days between half past midnight and 1:00 and wake up between 8:30 and 9:00 A.M. The midsleep times (on free days) of over 60 percent of the population fall between 3:30 and 5:30 A.M., but only less than half a percent between 1:30 and 2:00. These extreme larks begin their sleep on free days between 9:30 P.M. and 10:00 and wake up voluntarily between 5:30 A.M. and 6:00 (again assuming an eight-hour sleep duration). There are even more extreme early chronotypes, but their number is so low that the corresponding vertical bars are too small to be detectable in this graph. On the late side of the chronotype distribution, about four percent fall asleep between 3:00 and 3:30 A.M., and many more people sleep even later.

The distribution of midsleep in Central Europe.

So far, we have identified chronotypes primarily based on sleep habits, but it will become clear throughout this book that chronotype means much more. The internal timing of our body clock, of which sleep habits are just one aspect, dominates all functions in our body, ranging from genes being activated at certain times, to changes in body temperature and hormonal cocktail, right up to cognitive functions like the ability to do math. Magazine articles about the body clock often tell their readers when to do what: when to go to the dentist because the pain sensation is minimal; when to exercise because the training effect is greatest; when the best times are to do math or write poems or even when to make love. I am amazed and happy that the media pick up on the importance of our biological clock but also a bit worried that many of these articles approach this phenomenon naively. Some of them advise their readers, for example, to have sex in the morning. This advice is merely based on the fact that the male sex hormone testosterone peaks in the early morning hours. This may lead to an increased sex urge in men and may even ensure better male “performance.” But does this necessarily mean that sex is optimal for both partners at this time of day? Our biology concerns all aspects of our being, including our psychology and feelings, from pain to pleasure, and all these facets put together are more complex than the concentration of a single hormone, however important testosterone may be for sex. Thus, the media should use care when giving advice. This holds especially in light of what we have learned in this chapter: different people can have very different chronotypes with the extremes being up to twelve hours apart. So even if a piece of advice about when to go to the dentist was valid and useful, it would only be of limited help because an individual’s internal time could theoretically be as many as six hours earlier or later than the advised time.

We are capable of different things at different times of the day. Many aspects of performance show daily fluctuations, and their highs and lows depend on chronotype. Not only performance but many other aspects of life vary according to the time of day. If we wake up in the middle of the night, we don’t cook ourselves a meal—we are not hungry. So why should Ann be hungry just because she is being woken every school day at around her internal midnight? The quotation on Ann’s tee shirt questions why the early hours of the day have such a good reputation, with all those proverbs glorifying the early risers. Good question!

![]()

2

Of Early Birds and Long Sleepers

The sun had just risen above the horizon when the farmer walked along a country path toward his field. He cheerfully greeted a man he encountered halfway between the village and his destination. He thought to himself, “Must be a decent bloke to be up so early.”

The postman rang the doorbell at half past ten. If he hadn’t heard noises from within the apartment, he would have left long before. He rang the bell once more—longer and harder—a...