![]()

PART ONE

B+ Could Try Harder

![]()

1

DIARY OF A SCANDAL

The first hint of trouble came in the form of an e-mail message. It reached me on Friday, March 17, 2000, at 4:09 pm. The message was from a guy named Jeff in Erie, Pennsylvania, who was otherwise unknown to me. (He readily provided his full name and e-mail address, but I have suppressed them here, as a courtesy to him.)

At first, I couldn’t figure out why Jeff was writing to me. He kept referring to some college course, and he seemed to be very exercised over it. He wanted to know what it was really about. He went on to suggest that I tell the Executive Committee of the English Department to include in the curriculum, for balance, another course, entitled “How To Be a Heartless Conservative.” There was surely at least one Republican in the department, he supposed, who was qualified to teach such a course. But then Jeff made a show of coming to his senses. A conservative allowed in the English Department? The very idea was ridiculous. And on that note of hilarity, his message ended.

This was all very witty, to be sure. So far, though, it was not especially enlightening.

But soon it turned out that Jeff was not alone. A dozen e-mail messages, most of them abusive and some of them obscene, followed in quick succession. The subsequent days and weeks brought many more.

You may wonder, as I did myself, what I had done to deserve all this attention. Eventually, I realized that earlier on the same day, Friday, March 17, 2000, the Registrar’s Office at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where in fact I do teach English, had activated its course information website, listing the classes to be offered during the fall term of the 2000–2001 academic year. At virtually the same moment, unbeknownst to me, the website of the National Review, a conservative magazine of political commentary founded by William F. Buckley, Jr., had run a story in its series NR Wire called “How To Be Gay 101.” Except for the heading, the story consisted entirely of one page from the University of Michigan’s newly published course listings.

Staffers at the National Review may well be on a constant lookout for new material, but they are surely not so desperate as to make a habit of scanning the University of Michigan’s website in eager anticipation of the exact moment each term when the registrar announces the courses to be taught the following semester.

Someone must have tipped them off.

It later emerged that there had indeed been a mole at work in the University of Michigan Registrar’s Office. At least, someone with access to the relevant information had e-mailed it in early March to the Michigan Review, the conservative campus newspaper associated with the National Review and its nationwide network of right-wing campus publications. The Michigan Review had apparently passed the information on to its parent organization. Matthew S. Schwartz, a student at the University of Michigan who for two years had been editor-in-chief of the Michigan Review, coyly revealed in an article in the MR the next month that “a U-M conservative newspaper tipped off a National Review reporter” about the breaking story. After that, as Schwartz put it, “the wheels of dissemination were in motion. Word . . . trickled down through conservative circles, and the story was well on its way to mainstream media.”1

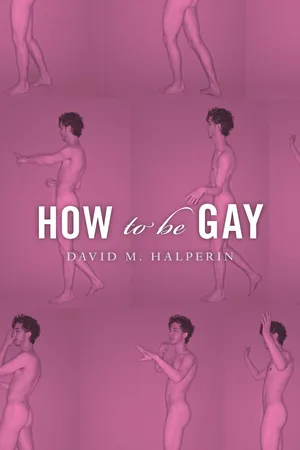

So what was this story that was just too good for the National Review to keep under wraps for a single day? It had to do with an undergraduate English course I had just invented, called “How To Be Gay: Male Homosexuality and Initiation.” The course description had been made public that morning, along with the rest of the information about the class. The National Review website withheld all commentary, introducing the story thus: “What follows is the verbatim description from the University of Michigan’s Fall 2000 course catalog. U. Michigan was ranked as the 25th best University in the United States in the most recent ratings by US News and World Report.”

The next year, our national ranking went up.

Here is the course description, as it appeared (correctly, except for the omission of paragraph breaks) on the National Review’s website.

Just because you happen to be a gay man doesn’t mean that you don’t have to learn how to become one. Gay men do some of that learning on their own, but often we learn how to be gay from others, either because we look to them for instruction or because they simply tell us what they think we need to know, whether we ask for their advice or not. This course will examine the general topic of the role that initiation plays in the formation of gay identity. We will approach it from three angles: (1) as a sub-cultural practice—subtle, complex, and difficult to theorize—which a small but significant body of work in queer studies has begun to explore; (2) as a theme in gay male writing; (3) as a class project, since the course itself will constitute an experiment in the very process of initiation that it hopes to understand. In particular, we’ll examine a number of cultural artifacts and activities that seem to play a prominent role in learning how to be gay: Hollywood movies, grand opera, Broadway musicals, and other works of classical and popular music, as well as camp, diva-worship, drag, muscle culture, style, fashion, and interior design. Are there a number of classically “gay” works such that, despite changing tastes and generations, ALL gay men, of whatever class, race, or ethnicity, need to know them, in order to be gay? What roles do such works play in learning how to be gay? What is there about these works that makes them essential parts of a gay male curriculum? Conversely, what is there about gay identity that explains the gay appropriation of these works? One aim of exploring these questions is to approach gay identity from the perspective of social practices and cultural identifications rather than from the perspective of gay sexuality itself. What can such an approach tell us about the sentimental, affective, or aesthetic dimensions of gay identity, including gay sexuality, that an exclusive focus on gay sexuality cannot? At the core of gay experience, there is not only identification but disidentification. Almost as soon as I learn how to be gay, or perhaps even before, I also learn how not to be gay. I say to myself, “Well, I may be gay, but at least I’m not like THAT!” Rather than attempting to promote one version of gay identity at the expense of others, this course will investigate the stakes in gay identifications and disidentifications, seeking ultimately to create the basis for a wider acceptance of the plurality of ways in which people determine how to be gay. Work for the class will include short essays, projects, and a mandatory weekly three-hour screening (or other cultural workshop) on Thursday evenings.

The National Review was right to think that no commentary would be needed. From the messages and letters I received, it was clear that a number of readers understood my class to be an overt attempt to recruit straight students to the gay lifestyle. Some conservatives, like Jeff from Erie, already believe that universities, and especially English Departments, are bastions of left-wing radicalism; others have long suspected that institutions of higher education indoctrinate students into extremist ideologies, argue them out of their religious faith, corrupt them with alcohol and drugs, and turn them into homosexuals. Now conservatives had proof positive of the last of those intuitions—the blueprint for homosexual world domination, the actual game plan—right there in plain English.

Well, at least the title was in plain English.

The course description for my class actually said nothing at all about converting heterosexual students to homosexuality.2 It emphasized, from its very first line, that the topic to be studied had to do with how men who already are gay acquire a conscious identity, a common culture, a particular outlook on the world, a shared sense of self, an awareness of belonging to a specific social group, and a distinctive sensibility or subjectivity. It was designed to explore a basic paradox: How do you become who you are?

In particular, the class set out to explore gay men’s characteristic relation to mainstream culture for what it might reveal about certain structures of feeling distinctive to gay men.3 The goal of such an inquiry was to shed light on the nature and formation of gay male subjectivity. Accordingly, the class approached homosexuality as a social rather than an individual condition and as a cultural practice rather than a sexual one. It took up the initiatory process internal to gay male communities whereby gay men teach other gay men how to be gay—not by introducing them to gay sex, let alone by seducing them into it (gay men are likely to have had plentiful exposure to sex by the time they take up residence in a gay male social world), but rather by showing them how to transform a number of heterosexual cultural objects and discourses into vehicles of gay meaning.

The course’s aim, in other words, was to examine how cultural transmission operates in the case of sexual minorities. Unlike the members of minority groups defined by race or ethnicity or religion, gay men cannot rely on their birth families to teach them about their history or their culture. They must discover their roots through contact with the larger society and the larger world.4

As the course evolved over the years, it grew less concerned with adult initiation and became more focused on the kind of gay acculturation that begins in early childhood, without the conscious participation of the immediate family and against the grain of social expectations. The course’s goal was to understand how this counter-acculturation operates, the exact logic by which gay male subjects resist the summons to experience the world in heterosexual and heteronormative ways.

That is also the goal of this book.

The course description indicated plainly that the particular topic to be studied would be gay male cultural practices and gay male subjectivity. The stated purpose of the course was to describe a gay male perspective on the world and to explore, to analyze, and to understand gay male culture in its specificity. Male homosexuality often gives rise to distinctive ways of relating to the larger society—to forms of cultural resistance all its own—so there is good reason to treat gay male culture as a topic in its own right. That is what I will do here.

Women have written brilliantly about gay male culture. (So have a few straight men.) Their insights played a central role in my class; they also figure prominently in this book. Studying a gay male perspective on the world does not entail studying it, then, from a gay male perspective. Nor does it entail excluding the perspectives of women and others. Nonetheless, describing how gay men relate to sex and gender roles, how they see women, and the place of femininity in gay male cultural practices does mean focusing on gay male attitudes toward women, not on women themselves, their outlook or their interests. It is the gendered subjectivity of gay men—both gay male masculinity and gay male femininity—that is the topic of this book. The fact that most of the women whose work I have depended on in order to understand gay male culture turn out to be gay themselves does not diminish the usefulness of considering male homosexuality apart from female homosexuality. (Since my topic is gay men, male homosexuality, and gay male culture, the word “gay,” as I use it here, generally refers to males, as it did in the title of my course. When I intend my statements to apply to gay people as a whole, to lesbians and gay men, or to queers more generally, I adjust my wording.)

The project of studying gay male culture encounters an initial, daunting obstacle. Some people don’t believe there is such a thing as gay culture. Although the existence of gay male culture is routinely acknowledged as a fact, it is just as routinely denied as a truth.

To say that gay men have a particular, distinctive, characteristic relation to the culture of the larger society in which they live is to do nothing more than to state the obvious. But despite how obvious such a statement may be—and despite how often, how commonly it is made—it is liable to become controversial as soon as it is asserted as a claim. That is especially the case if the statement, instead of being casually tossed off with a knowing wink, is put forward in all seriousness as a sweeping generalization about gay men.

That gay men have a specific, non-standard attachment to certain cultural objects and cultural forms is the widespread, unquestioned assumption behind a lot of American popular humor.5 No one will look at you aghast, or cry out in protest, or stop you in mid-sentence, if you dare to imply that a guy who worships divas, who loves torch songs or show tunes, who knows all of Bette Davis’s best lines by heart, or who attaches supreme importance to fine points of style or interior design—no one will be horrified if you imply that such a man might, just possibly, not turn out to be completely straight. When a satirical student newspaper at the University of Michigan wanted to mock the panic of one alumnus over the election of an openly gay student body president, it wrote that the new president “has finally succeeded in his quest to turn Michigan’s entire student body homosexual. . . . Within minutes . . . , European techno music began blaring throughout Central and North Campus. . . . The many changes . . . already implemented include requiring all incoming freshmen to take a mandatory three-credit course in post-modern interior design. . . . 94 percent of the school’s curriculum now involves showtunes.”6

Similarly, when a British tabloid wanted to dramatize the shocking case of a “typical, laddish, beer-swilling, sport-mad 20-something smitten with his fiancée” who became gay overnight as a result of an athletic...