![]()

SEKIGAHARA

1

In 1610 Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, gave his adopted daughter a pair of eight-fold screens as part of her dowry before sending her off to be the bride of Tsugaru Nobuhira. The screens depict the battle of Sekigahara, which took place in the ninth month of 1600, and established the political foundation for two and a half centuries of Tokugawa rule. They are in the style of the court school of Tosa painters, richly detailed and splendidly colored, painted on thin sheets of hammered gold that set off the epic deeds that they record. The narrative moves from right to left, as in a page of written Japanese, and begins with the arrival of the competing hosts the day before the battle. The village of Sekigahara is set in a narrow valley between the mountains of Mino Province. The rice harvest has been gathered; fall was a favorite time for the military commanders of the day, as they could seize the peasants’ produce after the harvest and avoid the work of transporting mountains of supplies. At the top the army of Ieyasu is shown joining the battle line; the future shogun himself is splendidly mounted and surrounded by his guard. Lower on those panels is the castle of ōgaki, which served as headquarters for the coalition of feudal chiefs, the daimyo, drawn up to oppose Ieyasu. Everywhere throughout the sixteen panels there are formations of soldiers, arranged below the tall cloth banners that announce their formation and lord. The men throng to the scenes of struggle, and break in defeat and flight. The samurai, resplendent in their armor, are on horseback; larger groups of foot soldiers armed with lances and swords surround and follow them. By the time the scene shifts to the sixteenth and final screen the army at the lower part of the screen is in flight, and from the surrounding hills men equipped with firearms are adding to the carnage by picking them off. Soon the heads of those who have fallen will be stacked in orderly piles to make possible a count of enemy dead. For the losing side modern estimates range from four thousand to twice that number; in any case an awesome harvest of the defeated host will be executed a few days later, and their gibbeted heads displayed in the nearby city.

The number of fighting men arrayed against each other was formidable. There were probably over 100,000 on each side, although the nature of the terrain meant that about half that many, perhaps 110,000, were actually committed to the battle. Sekigahara came as the climax to almost a century of intermittent warfare during which commanders had gained experience in moving large numbers of troops. The night before the battle not even a driving rain kept the hosts from assembling and taking up their positions, and on the morning hostilities broke out a dense fog brought units into contact before the word to attack had been given. Battle management was difficult because there were divisions sent by feudal lords from all parts of the country on both sides. From one such, the detachment of 3,000 men contributed by Date Masamune, daimyo of the northeastern domain of Sendai, one can get some idea of the proportions of weaponry in use. Date had 420 horsemen, 200 archers, 850 men carrying long spears, and 1,200 armed with matchlock firearms. Many also carried swords, the samurai two, one long and the other short, but the other weapons were the ones that counted more.

1. The Sengoku Background

Tokugawa rule was to be praised as the “great peace,” and to understand how grateful writers in early modern Japan were for the more than two centuries without conflict—a period during which China was overrun by the Manchus, India by the Moguls, and Europe was engulfed in a series of wars that culminated in the rise and fall of the Napoleonic empire—it is necessary to explain what had gone before. Tokugawa rule was not Japan’s first experience of unity and order. In the seventh and eighth centuries the introduction of institutions of central government modeled on those of China had also been followed by several centuries of peace broken only by border conflict to the north. The early government had purchased Chinese-style centralization for its heartland at the price of continued dominance for regional leaders at the periphery, however, and by the tenth century a movement of privatization had begun to replace the institutions of central rule. Grants of tax-free land to court favorites and to temples restricted the fiscal base of central government, and additional offices for the maintenance of order and land registration began to usurp the functions that had been set aside for the institutions of the imperial state. By the twelfth century power struggles between local grandees were affecting life in the capital. At the center the great Fujiwara clan, subdivided into several houses, reached into the court through marriage alliances and patronage, and so dominated life that emperors began to seek early abdication in order to be able to arrange their own lives and manage their own estates. The court itself was becoming more a private than a governmental institution, though its members continued to function as the most important of the lineages with which it was connected. Great Buddhist temples too served as centers of a network of subsidiaries with landed interests throughout the country. Ambitious men developed personal followings in the course of accumulating and managing private estates and managing the diminished part of the once universal public realm that remained. They began to arrange themselves in leagues that claimed and sometimes had lineage connections, and as their power grew the aristocrats at court tried also to utilize them for their needs.

In the twelfth century a series of wars among these aristocratic warriors—few in number, fiercely proud of their heritage, and splendidly accoutered and horsed—ended with victory for the Minamoto clan, which installed itself in headquarters at Kamakura on the Sagami Bay in eastern Japan. The office of shogun, theretofore a temporary commission used in pacification campaigns against the Ainu to the north, now became a permanent and hereditary title used to designate the head of warrior houses. Japan entered a period of warrior rule from which it did not emerge until the fall of the Tokugawa in 1868.

That period was nevertheless one of constant development and change. The first line of Minamoto shoguns—from whom the Tokugawa were to claim descent, albeit on dubious grounds—established a line of military authority that supplemented, and in time overshadowed, that of the imperial court. It forced from the court permission to appoint stewards to private estates throughout the land, and constables or military governors in the provinces to serve as officials of the new system of justice that was established. Although the Minamoto line itself soon ended, a line of regents, hereditary in the Hōjō family, carried on its functions. At the imperial capital the wishes of emperors, who frequently abdicated to exercise greater influence from monastic establishments, counted for much less. An attempt by a retired emperor to challenge Kamakura dominance was quickly snuffed out and led to more forceful measures by the Kamakura leaders. Shadow shoguns dealt with shadow emperors, and Kamakura institutions remained an overlay on those of the court. Gradually provincial and local interests came to count for more. The tenuous balance was brought to an end by the great invasions launched by the Mongol overlords of China in 1274 and 1281. Japan emerged from this crisis with its sovereignty intact, but its leaders had conquered no new lands with which they could reward their men. By 1333 a discontented emperor was able to rally enough discontented warriors to bring the Kamakura shogunate to its final crisis.

The second shogunal line, that of the Ashikaga, chose to establish its headquarters in the imperial capital of Kyoto. The title of shogun was now formally linked with the designation of leader of the military houses (buke no tōryō), but in fact he experienced increasing difficulty asserting his primacy over the provincial warrior administrators. The discontent the emperor had exploited to bring on the crisis of 1333 extended throughout that century. At a time when rival papacies at Avignon and Rome vied for authority in the West, competing military houses in Japan maintained rival imperial lines. Three-quarters of a century of warfare were brought to an end only by a compromise under which the two lines alternated in office. Meanwhile the power of the imperial house continued to diminish. Although the Ashikaga shogun’s writ did not run far beyond the heartland of classical Japan, within it his pretensions grew until the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu styled himself “King of Japan” when he engaged in foreign policy with the Ming emperors of China.

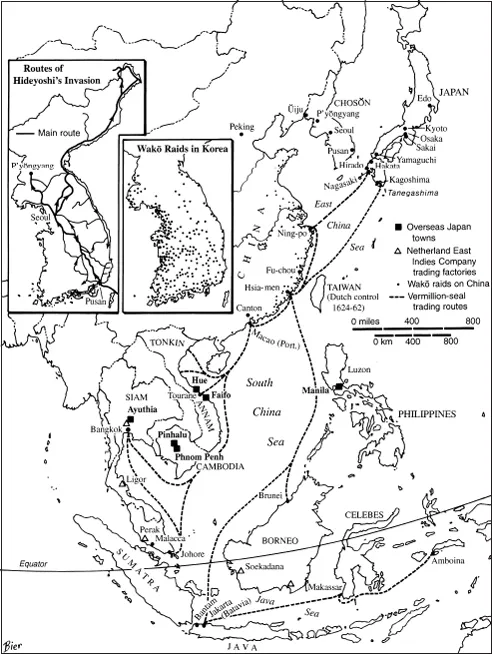

Yoshimitsu (1358–1408) was passionately eager to show himself a cultured aesthete capable of dealing with continental culture, and he was assiduous in collecting evidence of that cultivation in the form of paintings and ceramics. He had hundreds, perhaps thousands, of contemporaries who were no less eager, and much less restrained, in taking what they wanted. The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were conspicuous for the appearance of piracy that preyed on the settled civilizations of Korea and China. The wakō, as the raiders were called, were based for the most part on islands off the coast of the Japanese island of Kyushu. The weakness of central power and public order, and the high degree of commercial and military vigor that Japan’s warrior society began to generate, made Kyushu and its environs a perfect base from which Japanese buccaneers, Chinese expatriates, and Korean renegades could become a scourge for Japan’s neighbors. After the Koreans made adjustments that permitted a limited amount of trade for them at authorized ports, the brigands turned to Ming China, which brooked no compromise. In periods of relative strength, like that under Yoshimitsu, the Ashikaga shogunate was able to restrain the pirates, but after his death in 1408 the tide ran stronger than before. Within Japan political order disintegrated almost totally after a shogunal succession dispute in 1467 split the warrior leaders and led to the War of the Ōnin era. With Ming prohibitions on all trade the inhabitants of China’s coastal provinces were often willing to encourage “secret” trade that could easily degenerate into pirate raids, and in the mid-sixteenth century the situation reached crisis proportions. Flotillas of wakō ships carrying as many as several thousand armed men raided Chinese coastal areas for food supplies and anything else of value, in one case sweeping up to the very gates of Nanking. As in Elizabethan England, trade and piracy went hand in hand, but without the central authority and reward that London could contribute.

The Ōnin War began a long conflagration that effectively ended Ashikaga influence and rule. Japanese familiar with Chinese history referred to the era as “Sengoku,” the Age of Warring States that had preceded the establishment of China’s unitary empire. If the influence of the shogun was at a low ebb, so was that of the imperial court. In 1500 a new emperor, Go-Kashiwabara, had to wait twenty years for formal enthronement because funds were lacking. Not one of the Ashikaga shoguns of the sixteenth century served out his term without being driven from Kyoto at least once, and the only one to die in his capital was murdered there.1 Real power was beginning to lie with regional commanders, who were consolidating their holdings and followers while their betters fought themselves to a standstill at the center.

After the Ming rulers banned Japanese ships from their shores, trade for Chinese goods continued through the network of trading stations that was being developed by Chinese merchants throughout Southeast Asia. It was into this network that European traders and pirates, first Portuguese and then Spanish, English, and Dutch, worked their way from their bases in Macao, Manila, Indonesia, and India in the sixteenth century. The wave of Chinese commerce carried them to Japan. The Chinese privateer Wang Chih had based himself there, and the conqueror of Taiwan and chief problem for Manchu rulers (as well as for Dutch competitors), Cheng Ch’eng-kung (whom the Europeans and Japanese would refer to as Koxinga), was born on Kyushu of a Japanese mother and a Chinese father.

In 1543 two or three Portuguese traders arrived on board a Chinese junk at the island of Tanegashima, south of Kyushu. The island was, in the words of one authority, a “prolific breeding ground of pirates”;2 today it is the site of Japan’s principal rocket station. The Portuguese were carried to Japan “in the backwash of the wakō tide,”3 but they inaugurated a century of Iberian contact that included missionaries from the Society of Jesus, which had been formed a few years earlier; its disciplined, courageous, and often brilliant members were to play a remarkable role in Japan for the next half century. One of the most notorious wakō captains acted as their first interpreter, and St. Francis Xavier himself arrived from Malacca on board a pirate ship in 1549. As will be noted below, the missionaries’ courage and devotion were phenomenal; by the time Japan’s rulers turned against Christianity, expelling its missionaries and persecuting their converts, thousands had embraced the new faith. Konishi Yukinaga, a Kyushu daimyo who was on the losing side at Sekigahara, refused his followers’ entreaty to commit suicide and chose the humiliation of surrender and public execution rather than violate his Christian scruples against self-destruction.

1. Japanese raids, wars, and settlements in Asia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Wakō pirates, largely but not exclusively made up of Japanese, raided the Korean and Chinese coasts at the points indicated. In Southeast Asia Japanese trading ships led to the rise of “Japantowns” in Siam, Luzon, and other places. The left insert shows the route of Hideyoshi’s daimyo in the invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1598.

Yet the most immediate product of the first contact with the West was the introduction of firearms. The harquebus impressed the Japanese immediately, and the “Tanegashima iron rod,” as it became known from the place of its introduction, was speedily copied, improved, and produced in such numbers that, as the screen illustrations of the battle of Sekigahara show, it transformed warfare and became the instrument of the unification of Japan.

The Teppō-ki (The story of the gun) that was compiled for Hisatoki, lord of Tanegashima, gives this description of the islanders’ effort to square the new weapon with inherited philosophical ideas by describing how a Buddhist monk told about the encounter.

In their hands [the strangers] carried something two or three feet long, straight on the outside with a passage inside, and made of a heavy substance. The inner passage runs through it although it is closed at the end. At its side there is an aperture which is the passageway for fire. Its shape defied comparison with anything I know. To use it, fill it with powder and small lead pellets. Set up a small white target on a bank. Grip the object in your hand, compose your body, and closing one eye, apply fire to the aperture. Then the pellet hits the target squarely. The explosion is like lightning and the report like thunder. Bystanders must cover their ears …

Lord Tokitaka saw it and thought it was the wonder of wonders. He did not know its name at first, or the details of its use. Then someone called it “iron-arms” although it was not known whether the Chinese called it so, or whether it was so called only on our island. Thus, one day, Tokitaka spoke to the two alien leaders through an interpreter: “Incapable though I am, I should like to learn about it.” Thereupon, the chiefs answered, also through an interpreter: “If you wish to learn about it, we shall teach you its mysteries.” Tokitaka then asked, “What is its secret?” The chiefs replied: “The secret is to put your mind aright and close one eye.” Tokitaka said: “The ancient sages have often taught how to set one’s mind aright, and I have learned something of it. If the mind is not set aright, there will be no logic for what we say or do. Thus, I understand what you say about setting our minds aright. However, will it not impair our vision for objects at a distance if we close one eye? Why should we close an eye?” To which the chiefs replied: “That is because concentration is important in everything. When one concentrates, a broad vision is not necessary. To close an eye is not to dim one’s eyesight but rather to project one’s concentration further. You should know this.” Delighted, Lord Tokitaka said: “That corresponds to what Lao Tzu has said, ‘Good sight means seeing what is very small’” …

It is more than sixty years since the introduction of this weapon into our country. There are some gray-haired men who still remember the event clearly. The fact is that Tokitaka procured two pieces of the weapon and studied them, and with one volley of the weapon startled sixty provinces [i.e., all Japan] of our country. Moreover, it was he who made the iron-workers learn the method of their manufacture and made it possible for that knowledge to spread over the entire length and breadth of the country.4

2. The New Sengoku Daimyo

The early decades of sixteenth-century Japan were remarkable for the variety of patterns of control, landholding, and taxation that prevailed. In some areas the shōen, estates granted to powerful families or temples by the Heian (Kyoto) court as its power waned in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, survived, but they had become steadily more free from outside interference. Proprietors delegated administration and order to local notables; myōshu, lineage members whose names became attached to their lands, dominated lesser farming families and kept order for representatives of shogunal power who held titles like “military steward” or “provincial constable.” In areas more distant from the imperial capital local warrior families had substantially taken over from the representatives of the center, and “men of the land” (kokujin) became forces to be reckoned with. Still other local military men, who styled themselves samurai (from saburau, to serve) in evocation of the professional warriors at the capital, emerged as keepers of the peace in areas where government lands had never been transferred to the private estates. The warfare that followed the succession dispute of the Ōnin era in the fifteenth century naturally accentuated the variety and confusion, until parts of Japan became a welter of conflicting jurisdictions and procedures.

In the 1500s, however, parallel and uniform trends in major parts of the country began to bring pattern to this confusion. Quiet but significant increases in agricultural productivity were accompanied by greater commercial growth and monetization of transactions. The explosion of brigandage that swept the coasts of China and Korea was in part a reflection and in part a by-product of this economic growth. With it came institutional changes and improvements in the technology of rule. Add the changes in military technology that followed the introduction of firearms, the larger scale of control, and more effective methods of exploitation, and profound change came to most areas of central Japan. In explaining this, Japanese historians frequently refer to “Sengoku daimyo,” who differ from “shugo [constable] daimyo” of late medieval times, to illustrate the contrast between the variety and confusion of conditions in the fourteenth century chaos and the emerging order of the sixteenth century.

The new daimyo were far more powerful within their realms than the shugo daimyo had been in theirs; the latter had been appointees and subject to constraints of shogunal power and aristocratic and temple proprietors who were quick to complain about their excesses at the court, but the Sengoku daimyo, their power established through military tactics and buttressed by greater resources, were able to make greater demands of their vassals and hold their own ag...