![]()

PART ONE

The Count, Context, and Conditions

![]()

1

THE SCOPE AND PATTERN OF OVERSEAS TRAINED TEACHERS IN U.S. SCHOOLS

Overseas trained teachers (OTTs) are a growing source of U.S. teacher labor, particularly in the math, science, and special education departments of high-poverty urban centers. Urban school districts seek OTTs when the domestic American market fails them. They draw on the overseas market to staff the highest-need subject areas in low-income schools with teachers who meet the qualified teacher policy requirements.

The scope and pattern of OTTs in the United States is discernible through the collective analysis of immigration visa data and California state teacher credentialing data as well as through interviews with teachers, recruiters, and school leaders. In particular, data regarding the two most common OTT visas—H1B labor shortage visas and J-1 cultural exchange visas—highlight national trends. California state teacher credentialing data offers a window into the employment patterns of OTTs over a longer period of time and reveals each teacher’s country of origin. From this analysis we can see the special case of the Philippines as a significant source of teachers for California schools.

Difficult to Discern

It is difficult to discern the scope and pattern of overseas teachers in the United States. Although schools and states report teacher ethnicity, gender, age, years teaching, credential status, and more—they are not required to report nationality or visa status. For one thing, teachers are recruited on multiple types of visas and the information available on those visas is minimal and variable. Many states collect data on country of teacher education in the credentialing process; however, that information is generally internal, unreported, and disconnected from place of employment and visa type. Furthermore, many teachers are recruited by agencies and placed in schools throughout the United States. These agencies do not need to report their placement patterns.

There is no clear and simple visa for guest teachers as there was for farm workers during the U.S. Braceros program of the 1940s through 1960s, or as there is currently for foreign nurses today.1 Instead, OTTs are mixed into a sea of labor-shortage visas—a pattern that is obscured through the use of cultural exchange visas. Finding the scope and pattern of OTTs using standard immigration or education reporting systems is like using a satellite map to try to identify the colors and styles of individual houses—you can, but it is time consuming and prone to error, and it requires further verification. Determining the scope and pattern of OTTs is thus a time-consuming process that requires multiple data sources in order to minimize error and ensure accuracy.

Documenting the distribution of OTTs requires accounting for teachers working on both H1B labor shortage visas and J-1 cultural exchange visas—neither of which is readily documented, though for different reasons.

The J-1 Visa

The J-1 visa is issued through the U.S. Department of State, which has this to say on its website about the exchange visitor program:

The Exchange Visitor Program promotes mutual understanding between the people of the United States (U.S.) and the people of other countries by educational and cultural exchanges, under the provisions of U.S. law. Exchange Programs provide an extremely valuable opportunity to experience the U.S. and our way of life, thereby developing lasting and meaningful relationships.2

Designed to allow for cultural exchange, J-1 visas are generally issued for one year and are renewable up to two times for a maximum of three years. Only authorized agencies can host J-1 visas and they typically require evidence of a two-way cultural exchange. Many live-in nannies are recruited on J-1 visas: Their host agencies must ensure they attend classes that will enrich their experience in the United States, and the nannies must document how they share their home culture with the children in their care. Universities also often rely on J-1s for international scholars. The visa recipient, not the employer, pays the costs associated with a J-1 visa, which is predicated on the assumption and requirement that visa holders will return to their home countries to complete the circle of exchange. There is no annual cap on J-1 visas and the numbers and distribution of them is not readily available to the public. They are seen as a cultural exchange visa rather than a work visa and, therefore, they are not an issue related to the labor market or economy.

It was only through teacher interviews conducted for this book that it became apparent that many overseas teachers are recruited on J-1 visas and that these teachers and their visas are under the radar of any reporting mechanism. There is no current way to approximate the number of teachers working on J-1 visas in the United States or to determine their distribution. Most of the case study teachers in this book started on J-1 visas with the idea of converting to an H1B. The J1 visa must be sponsored by an agency with an established visitor exchange program as designated by the U.S. Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. These agencies are responsible for ensuring that the visa conditions are met—including a two-year mandatory repatriation clause intended to ensure teachers return to their home countries to complete the circle of exchange and their time as a visitor. In order to be considered a visitor, a teacher must at some point go home—thus fulfilling the temporary status J-1 visa requirements.

There are a few exceptions, and some school districts have become known among the teachers as employers that offer longer-term H1B labor shortage visas. In California, however, J-1 visas are the most common initial teacher visas among teachers interviewed for this book.

The H-1B Visa

The U.S. Department of Labor offers this explanation for its H-1B program:

The H-1B program allows employers to temporarily employ foreign workers in the U.S. on a nonimmigrant basis in specialty occupations or as fashion models of distinguished merit and ability. A specialty occupation requires the theoretical and practical application of a body of specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent in the specific specialty (e.g., sciences, medicine, health care, education, biotechnology, and business specialties, etc . . .).3

Unlike J-1s, H1B visas are designed to enable employers to fill labor shortages by recruiting overseas. Many people are familiar with the H1B visa—but most think of it as a high tech or science oriented visa—one that employers such as Microsoft lobby to protect and increase in order to help ensure U.S. competitiveness in computer engineering. Congress does, however, designate approved labor shortage areas: education is an approved field and schoolteacher is an approved profession, though these regulations do not specify certain subject or grade level designations.

An H1B visa allows three years of employment and is renewable for a second three-year cycle. Although it is not an immigration visa, it is considered convertible because a visa holder can apply for a green card while working on an H1B visa. Subject to an annual cap set by Congress, H-1B visas are distributed in most years through a lottery process in April for October work start dates. The lottery is a competitive process, so receiving a visa is by no means a certain outcome. Renewals are exempt from the annual cap, as are employees affiliated with a university or other research institution. Actual H1B recipients, both employers and employees, are not reported publicly, making H1B scope and pattern difficult to definitively discern.

Although the number of teachers in the United States on an H1B visa is difficult to discern, this number can be approximated by analyzing the employer applications for U.S. Department of Labor condition certifications for positions they seek to fill with overseas employees. The Labor Condition Application (LCA) is the precursor to the H1B visa and has been required by law since January 2001. Seeking to certify a position with the Department of Labor signals interest and intent to seek an overseas trained teacher on an H1B visa. Getting the position certified authorizes the employer to seek the overseas employee and the H1B visa. It does not guarantee that the employer will find a suitable candidate, nor does it ensure that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security will issue an H1B visa. The visa is, of course, subject to the lottery. Because Congress requires this DOL labor condition certification process to be reported publicly, the data generated permit an approximation of the scope and pattern of overseas trained teachers in the United States. While not a perfect measure, it is the only current means of perceiving national patterns.

The national scope and pattern analysis that follows here is based on the Labor Condition Applications made for teachers and certified by the Department of Labor between 2002 and 2008. These numbers represent employer intent and interest to employ overseas trained teachers. They do not include teachers hired on J-1 visas, nor do they exclude LCAs that did not result in a successful hire with an H1B visa. Therefore, these numbers can be seen to both underreport and overreport the scope of OTTs in the United States, although they are most useful as a way of revealing patterns. Consequently, they are discussed here as “effort to employ” OTTs rather than as hires or actual teachers. The LCA numbers allow a look at which employers in what regions of the country and demographic communities sought to employ overseas trained teachers, and they reveal patterns clearly. Interest in overseas trained teachers is concentrated in high-poverty urban communities with schools that primarily serve low-income, nonwhite students for whom English is not their first language.

High Poverty Urban Concentrations

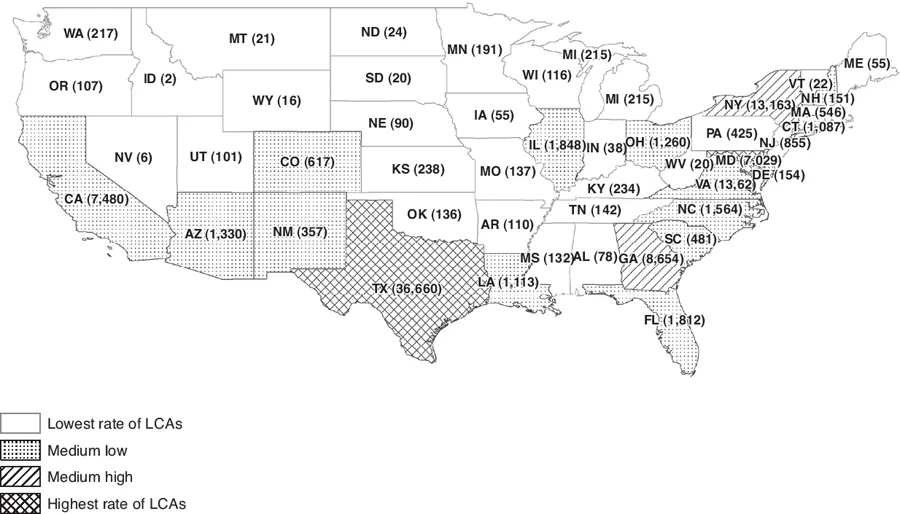

Between 2002 and 2008, U.S. public schools sought to employ 91,126 OTTs with labor shortage visas (H1Bs). Ten states captured 78,073 of those, and just three states—Texas, New York, and California—account for 57,187, nearly two-thirds of all OTTs sought nationwide. State population alone does not account for these concentrations. Even when teacher employment efforts are looked at in relation to the numbers of public school students per state, Texas, New York, and California still lead the nation. Although we would expect states with higher numbers of students to seek higher numbers of teachers, these states, even when normalized for student population size, still lead the nation in seeking to employ overseas trained teachers, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

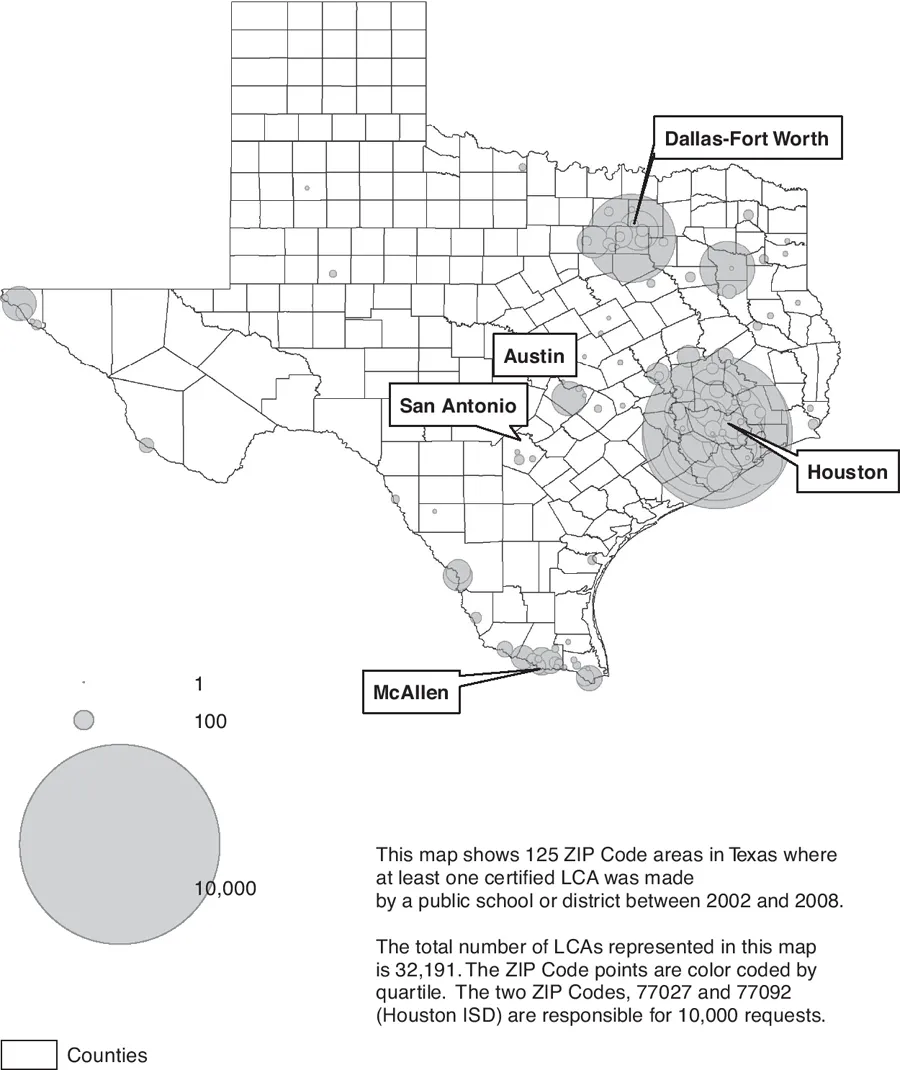

Texas leads the nation with 36,330 OTT searches initiated between 2002 and 2008—one-third of all searches nationwide, although it would be more accurate to say that Houston, rather than all of Texas, leads the nation in the number of OTT searches. Ten thousand such searches were initiated in just two central Houston zip codes, and the greater Houston area accounts for a third of all Texas searches. When Dallas, Austin, Waco, and the Mexican border area of McAllen are included, most efforts to employ OTTs in Texas are captured in these areas, as shown in Figure 1.2).

In New York state, the concentration of OTTs in impoverished urban areas is even clearer. If you are an OTT in this state, then you probably teach in New York City. While New York state school employers sought 13,131 OTTs between 2002 and 2008, New York City initiated 94 percent (12,374) of the searches. Ranking overseas teacher searches by state puts Texas as the leader, but ranking by urban centers puts Houston and New York City on equal ground.

Figure 1.1 Number of teacher LCA applications by state, 2002–2008, normalized by public school student population.

The story is similar in California. The state has almost a thousand school districts but OTTs are not evenly distributed among them, being concentrated instead in just twelve high-poverty, low-achieving urban school districts. Twelve school districts account for 68 percent of the 7,438 H1B visas sought for OTTs in California between 2000 and 2006. These twelve school districts serve more than a million K–12 students, including about a quarter of the state’s recipients of free and reduced lunches. Their student populations are predominantly nonwhite English language learners. In fact, in 2006, all twelve of the school districts where H1B visa requests were concentrated had fewer white students and more English language learners than the state average and, in ten of the twelve, free and reduced lunches were higher than the state average. The only area in which these school districts fell below the state average was in the percentages of fully qualified teachers employed. All twelve have historically depended on underqualified teachers to ensure adequate staffing numbers. These districts have had success in increasing their percentages of fully qualified teachers between 2001 and 2006—and OTTs are one way they have achieved this increase.

Figure 1.2 Within-state concentrations of teacher LCA applications in Texas (locations of major cities on this map are approximate).

California’s District A, while an extreme case in terms of the sheer number of teachers it sought, is typical of employing districts in terms of its student demographics. Set in a city with a population of just fewer than 100,000, District A is home to roughly 30,000 K–12 students. In 2001, 99 percent were nonwhite, with one-third of those students African American and two-thirds Latino. Sixty-one percent were English language learners and 71 percent lived below the poverty level. District A served these students with 1,367 teachers—66 percent of whom were not fully qualified. While District A’s student population changed little between 2001 and 2006, its teacher population altered significantly. The district reduced its percentage of unqualified teachers from the 2001 high of 66 percent to a 2006 low of just 27 percent. During that same time period, District A had 1,379 teaching positions certified by the U.S. Department of Labor as meeting the conditions for an H1B labor shortage visa. If each of these job certifications resulted in a person with a visa, District A could have replaced every one of its teachers with an OTT who met the state credentialing standards. In fact, interview data bears out that District A did draw heavily on the overseas labor market in altering its workforce composition. According to Eduardo Ferraro, one of the many overseas teachers recruited to District A from Spain, “District A hired hundreds of Spanish teachers . . . and then they switched for a time to Mexico, and now they are probably recruiting Filipino teachers.”

Eduardo’s exchange was facilit...