![]()

ONE

Granted the Law

Alfred Russel Wallace’s Evolutionary Travels

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE’S road to accepting the idea of transmutation of species was short: one reading of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1845 was sufficient to convince him of the essential correctness of the idea. His journey to deep insight into the phenomenon, however—his intellectual journey adducing the evidence in support of the idea and figuring out the mechanism behind it—was rather longer, but not exceedingly so: his Sarawak Law paper was published just ten years later, and the Ternate essay announcing his discovery of the mechanism of species change three years after that. When Wallace wrote to his friend Henry Walter Bates in December 1845 that the “development hypothesis” was “an incitement to the collection of facts, and an object to which they can be applied when collected,” what he had primarily in mind was facts pertaining to his “favourite subject,” namely, “the variations, arrangements, distribution, etc., of species” (Wallace Correspondence Project [WCP] 346)—in essence, facts of geographical distribution of species. In this chapter I trace Wallace’s “evolutionary” thinking, to use a modern term, from his initial conviction of the reality of transmutation to the triumphant announcement of its mechanism in his Ternate essay. His evolutionary travels began in earnest in Leicester, but the road took him to Amazonia and then Southeast Asia—an intellectual journey that can be traced through Wallace’s papers, journals, and notebooks in this period, with special emphasis on the “Species Notebook” (Linnean Society MS 180, Linnean Society of London). In this most important of his field notebooks, kept between 1855 and 1860 or so, Wallace reveals his far-ranging and creative insights into the species question (Costa 2013a).

Inspiration and Context

Beyond mere species variation, the geographical distribution of species and varieties lay at the heart, Wallace felt sure, of the species problem. This had long been recognized in a botanical context through the efforts of the polymath Prussian explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), whose writings Wallace eagerly consumed in his teens. Humboldt had devised the technique of “botanical arithmetic” to sleuth geographical patterns in species richness relative to genera and levels of endemism (Browne 1980). He urged comparative analysis of biota, such as new-world versus old-world species, to gain insight into the big philosophical question of the “creative power” behind species. The Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle (1778–1841), an admirer of Humboldt, famously declared in his Essai élémentaire de géographie botanique of 1820 that “all of the theory of geographical botany rests on the particular idea one holds about the origin of living things and the permanence of species.” Wallace had a taste for botany since about 1838, when, at the age of fifteen, he purchased his first botanical manual: the fourth (1841) edition of John Lindley’s Elements of Botany. The book proved to be disappointing since it was more a treatise on principles of plant anatomy and classification than identification manual, but Wallace annotated it heavily with, among other things, notes from John Claudius Loudon’s Encyclopedia of Plants and Humboldt’s Personal Narrative of Travels in South America; he even copied out passages from Charles Darwin’s Journal of Researches—passages that celebrated the “gorgeous beauty” and “luxuriant verdure” of tropical forests (McKinney 1972, 3–5). What better place to hunt for clues than in what seemed the very manufactory of species: the teeming tropics, with species richness dizzyingly far beyond anything that a denizen of the north-temperate zone could imagine?

Two other authors read by Wallace by the mid-1840s left a powerful impression on him: “Mr. Vestiges,” the then-anonymous author of the above-mentioned sensational Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (first published in 1844), and geologist Charles Lyell (1797–1875), author of the landmark Principles of Geology (first published 1830–1833). In some ways antithetical to one another, these two works nonetheless presented to Wallace new and exciting insights into the nature of the earth and its inhabitants. Vestiges presented a sweeping view of cosmological, planetary, and organic transmutation that extended even to people and social institutions—more than scandalous, some saw it as seditious. But the book was nothing if not a sensation, as meticulously documented in James Secord’s aptly titled history of the book’s reception, Victorian Sensation (Secord 2000). Vestiges also had the beneficial effect of airing the tainted subject, bringing discussions of transmutation into drawing rooms and parlors across a broad social cross section of the country (Secord 2000, 1–6). Edinburgh writer and publisher Robert Chambers, the anonymous author, was wise to keep his identity a secret, judging from the vehement condemnation of the book from pulpits to Parliament and the scientific salons of England.

Why such vehemence? In the first half of the nineteenth century, the doctrine of transmutation had become repugnant to the scientific and clerical establishment (often one and the same) owing to its connection with the radical French “transformists” of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with atheistic implications. Zoologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (1744–1829) was the best-known exponent of French transformism, and his ideas found currency in some thinkers across the channel—two prominent examples being Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802) and Scottish zoologist Robert Edmond Grant (1793–1874) (Corsi 1978, 2–5; Sloan 1985, 73–80). Erasmus, grandfather of Charles Darwin, was a famous physician and poet who put his ideas about the origin of life and organic transmutation into verse; Grant was Charles’s first scientific mentor when Charles was a medical student at Edinburgh (and surely provided the young Darwin’s second exposure to transmutationist thinking after his grandfather’s writings). Charles Darwin was no transmutationist at Edinburgh or Cambridge in the years that followed (1828–1831), however; the respectable naturalist-clerics who taught Darwin at Cambridge were strictly orthodox on this count, and some vehemently denounced Vestiges. But by the time Vestiges came out in 1844, Darwin had long since changed his mind and secretly embraced a view of species change. Like Wallace he agreed with the basic transmutational premise of Vestiges, though he deplored its lack of philosophical or scientific rigor.

Not so the twenty-two-year-old Wallace, who was more broadly enthusiastic. Victorian England was abuzz with the discreditable Vestiges, and Wallace eagerly devoured the book. In a November 1845 letter to Bates, he wrote, “Have you read ‘Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation,’ or is it out of your line?” Bates evidently was not as impressed as Wallace was, provoking Wallace to write a month later:

I have rather a more favorable opinion of the “Vestiges” than you appear to have—I do not consider it as a hasty generalisation, but rather as an ingenious hypothesis strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies but which remains to be proved by more facts & the additional light which future researches may throw upon the subject.—it at all events furnishes a subject for every observer of nature to turn his attention to; every fact he observes must make either for or against it, and it thus furnishes both an incitement to the collection of facts & an object to which to apply them when collected—I would observe that many eminent writers gave great support to the theory of the progressive development of species in Animals & plants. (WCP346)

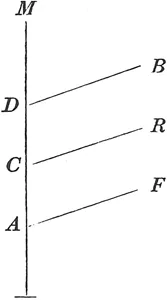

The genealogical model of descent that Wallace came to embrace was likely inspired by the treelike diagram of relationships in Vestiges, a diagram that represented embryological development but with transmutational implications (Figure 1.1). The author was careful to point out that the diagram “shews only the main ramifications; but the reader must suppose minor ones, representing the subordinate differences of orders, tribes, families, genera, &c.” (Chambers 1844, 212).

This process of differentiation set up an inquiry into how changes in embryological development can lead to transmutation: “it is apparent that the only thing required for an advance from one type to another in the generative process is that, for example, the fish embryo should not diverge at A, but go on to C before it diverges, in which case the progeny will be, not a fish, but a reptile” (Chambers 1844, 213). Geographical distribution also figured prominently in the Vestiges, as holding essential clues to the process of progressive development. Mr. Vestiges provided a set of “general conclusions regarding the geography of organic nature” in his chapter discussing the “Progress of Organic Creation”:

(1.) There are numerous distinct foci of organic production throughout the earth. (2.) These have everywhere advanced in accordance with the local conditions of climate &c., as far as at least the class and order are concerned, a diversity taking place in the lower gradations. No physical or geographical reason appearing for this diversity, we are led to infer that, (3.) it is the result of minute and inappreciable causes giving the law of organic development a particular direction in the lower subdivisions of the two kingdoms. (4.) Development has not gone on to equal results in the various continents, being most advanced in the eastern continent, next in the western, and least in Australia, this inequality being perhaps the result of the comparative antiquity of the various regions, geologically and geographically. (Chambers 1844, 190–191)

About the same time as reading Vestiges, Wallace read Lyell’s Principles of Geology. Principles was already in its sixth edition when Vestiges came out, so the transmutationist foil for Lyell was Lamarck. Still, the near-contemporaneous reading of Vestiges and Principles by Wallace is important. Mr. Vestiges and Lyell disagreed on many things, but they seemed to agree on the critical importance of geographical distribution for understanding the nature of species. Lyell opened his chapter on “Laws which Regulate the Geographical Distribution of Species” in volume 2 of Principles declaring:

Next to determining the question whether species have real existence, the consideration of the laws which regulate their geographical distribution is a subject of primary importance to the geologist. It is only by studying these laws with attention, by observing the position which groups of species occupy at present, and inquiring how these may be varied in the course of time by migrations, by changes in physical geography, and other causes, that we can hope to learn whether the duration of species be limited, or in what manner the state of the animate world is affected by the endless vicissitudes of the inanimate. (Lyell 1832, 66)

Figure 1.1. Tree of embryological differentiation of four vertebrate classes (F = fish, R = reptiles, B = birds, and M = mammals) from Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, inspired by William Carpenter’s concept of successive differentiation of vertebrate embryos (Carpenter 1841, 196–197). “The foetus of all the four classes may be supposed to advance in an identical condition to point A. The fish there diverges and passes along a line apart, and peculiar to itself, to its mature state at F. The reptile, bird, and mammal, go on together to C, where the reptile diverges in like manner, and advances by itself to R. The bird diverges at D, and goes on to B. The mammal then goes forward in a straight line to the highest point of organization at M” (Chambers 1844, 212). Courtesy of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Lyell’s influence on Wallace went far beyond an incitement to study the laws of distribution, however. The Principles also articulated powerful statements on the history of the earth and its inhabitants. Earth history was seen in terms of slow, steady change, a product of the long-continued action of natural forces still seen in action today—a principle called “actualism” in Wallace’s day, and “uniformity” today. Wallace wholly embraced this exciting new view of the planet’s transformations, but the other great statement articulated by the Principles had the opposite effect: Lyell’s strong anti-transmutationism. Lyell went to great lengths to argue against the doctrine point by point, and Wallace’s answers to many of these points are first articulated in the Species Notebook.

Collectors in Paradise

Such reading clearly had an effect on Wallace, and he began to think big—geographically and philosophically speaking. In the fall of 1847 he visited the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris in the company of his francophone sister Fanny, and soon afterward the insect room of the British Museum. Not long after his visit to the “fair city of Paris” he wrote to Bates: “I begin to feel rather dissatisfied with a mere local collection; little is to be learnt by it. I [should] like to take some one family, to study thoroughly—principally with a view to the theory of the origin of species. By that means I am strongly of [the] opinion that some definite results might be arrived at.” Wallace then asked Bates to help “in choosing one that it will be not difficult to obtain the greater number of the known species” (WCP348). Wallace might have become a “museum-man,” as they were called in those days, poring over pinned specimens from far-flung regions housed in row upon row of orderly cabinets in the great museums. But he no doubt realized early on that the breathtaking riches of the museum were in large measure unsuitable for the kind of analysis he had in mind. They boasted rich diversity, yes, and in some taxonomic groups perhaps even complete sets of species, but knowledge of many groups and regions was spotty. Then, too, the specimens often bore imprecise information on the locality in which they had been collected. He was to later exhort his fellow naturalists to pay closer attention to precisely where specimens came from, as he realized that only with such information could the long-sought patterns underlying geographical distribution of species and varieties be divined.

No, mere museum work would not do, and it was around this time Wallace determined to gather such information himself, hatching with kindred spirit Bates an audacious plan (Bates 1863, iii; Wallace 1905, 1:254). Over the subsequent autumn and winter of 1847–48 their plans to become collector-naturalists in some exotic locale took shape. Where to go? W. H. Edwards’s effusively romantic book A Voyage Up the River Amazon (1847) was the deciding factor—by chance they met Edwards, who was encouraging and even wrote them letters of recommendation. Despite what they must have soon realized were the many inaccuracies of Edwards’s book once they arrived in Amazonia, the choice was a fruitful one in many respects. Wallace and Bates were fortunate to be taken on by the able agent Samuel Stevens of Bloomsbury Street, London (Stevenson 2009), who helped them get outfitted and provided all manner of advice. The two met in London that March, booked passage on a trans-Atlantic ship, and departed from Liverpool in April. They soon arrived in the New World, literally and figuratively, landing at Pará, Brazil, on 26 May 1848, eager to explore “some of the vast and unexamined regions of the province … said to be so rich and varied in its productions of natural history” (Wallace and Bates 1849, 74).

Of the duo Wallace at that time was perhaps the more philosophically inclined, and he seems to have been especially keen on the question of species origins. He took to heart the pronouncements of Humboldt, Lyell, and others about the importance of geographical distribution in his pursuit of the species question—indeed, there is perhaps no clearer statement of this than Wallace’s declaration in his 1853 travel memoir A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro: “There is no part of natural history more interesting than the study of the geographical distribution of animals” (Wallace 1853, 469). But it is important to bear in mind that Wallace’s starting point was a conviction that the idea of species change was fundamentally correct—that is, he started with the working assumption of transmutation, and proceeded to collect data and observations in the area he thought most likely to yield insights. Lewis McKinney put it well when he commented that “zoogeography did not lead Wallace to evolution; on the contrary, evolution led him to the phenomena of the geographical distribution of organisms” (McKinney 1966, 357). And observe he did. In Wallace’s most important writings from his four years in Amazonia we see him circling around the species question, putting his finger on fundamental problems of variation and distribution in his attempt to ferret out the underlying patterns he thought must be there, and would once elucidated throw open a window on the mystery of species origins.

Though by necessity a working collector, Wallace sold only his duplicate specimens to finance his expeditions, saving most of the fruits of his labors for his personal scientific studies. His collecting efforts over four years in Amazonia were directed at problems of species distribution in one form or another (George 1964; Brooks 1984). He was fascinated by species that appeared to be restricted to particular locales, as seen in his pursuit of the Guianan cock-of-the-rock Rupicola rupicola (Cotingidae), which is restricted to a small area of granitic highlands occurring in the mountains of Guiana (Figure 1.2). Yet it was groups of species that held the greatest potential for shedding light on the species problem, by potentially providing a series that might map onto geography in illuminating ways. His working hypothesis while collecting in South America had an important geological component: geologically younger, newer, dynamically changing areas may, he thought, be inhabited by more recently derived species transmutated from related older species that occupy older geological formations. The great Amazon basin was a testing-ground for this idea, since the vast valley largely cons...