![]()

CHAPTER 1

COLLECTING BODIES for SCIENCE

Starting in the 1870s, whispers about fantastic discoveries in the American West began attracting attention. As settlers and explorers roamed the continent, some parties uncovered unusual and remarkably well-preserved human bodies previously unknown to science. Tucked deep into caves, buried near elaborate ruins, or frozen in arctic permafrost, naturally mummified corpses stupefied early observers. Unbeknownst to many of the people uncovering remains, the bodies were becoming critical in shaping emerging fields, including archaeology and anthropology in North America. At issue was not just what to do with ancient remains when found but also how best to interpret their significance. Despite the potential importance of mummies for understanding prehistoric history in the Americas, many people viewed these ancient corpses through the same lens driving the collection of skeletons of the more recent dead—scientific theories about race. When new bodies were discovered, the first questions usually focused on the racial origin of the mysterious bodies and their relationship to the modern races of the Americas. While the age of these mummies made them an important rarity, the primary purpose for collecting and permanently preserving new skeletons was to fit them into the puzzle that was the taxonomy of races. Nineteenth-century scientific publications and debate about racial divisions seemed only to fuel popular desires to collect human skeletons and mummies. Museums in the United States, aiming to catch up with their older European counterparts, began collecting bodies in North America with heretofore unseen zeal.

Naturally mummified remains fascinated scholars yet were also recognized as more than mere tools for archaeological science. In the late nineteenth century, American mummies captured popular imagination in a manner parallel to the prevailing Victorian-era obsession with Egypt in Britain. Certainly, the colonialist mania for collecting Egyptian antiquities took root in North America at the same time, but the puzzle of mummies from an ancient civilization in the American Southwest diverted attention to the mystery of the so-called cliff dwellers.

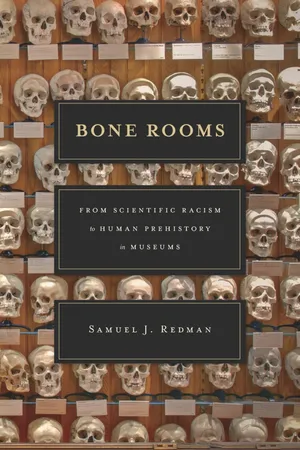

Following the Civil War, the number of museums collecting skeletons and mummies with the intention of studying racial science grew at a slow but steady pace. Major museums in the United States gradually built human remains collections around the expanding sciences of physical anthropology and comparative anatomy. Museum leaders came to view acquiring skeletons as a wise investment in emerging scientific disciplines. Natural history museums, in particular, began collecting skulls of nonwhite individuals, hoping to build on the work of people like the professor and physician Samuel George Morton, who had earlier amassed a collection of several hundred skulls and published a series of highly influential books based on his observations. Now considered inconsistent, pseudoscientific, ethically flawed, and marred by racism, Morton’s work was nevertheless highly regarded at the time. The influence of his work helped frame future debates in physical anthropology.1

Like Morton, early museum collectors opportunistically collected skulls from distant contacts and acquaintances. Many also fashioned racial taxonomies after Morton’s theories of the existence of particular racial groups. Private physicians and early amateur collectors, too, established skull collecting as a popular tradition in the United States. Mysterious packages would arrive at museums—sometimes accompanied by vague, handwritten notes with brief descriptions of the bones inside. Medical officers working as agents for the Army Medical Museum (AMM) were among the first to systematically collect skeletons for a major museum collection in the United States. Where army medical officers first trod, postal carriers soon followed, making it possible for amateur collectors to ship skeletons from far-flung locales to museums in Chicago, New York, or Washington, DC. As professional archaeologists began their work in the American West, amateurs chose to collect skulls and artifacts on their own. For many museums, knowing the racial origin of the specimen was enough to assign it a catalogue number and carefully place it into a drawer in a bone room.2

In 1875, when mummies were discovered in the Aleutian Islands, the New York Times referred to them as “a discovery of momentous interest to the scientific world.”3 Archaeologists, anthropologists, and even private corporations that had been collecting in Alaska for decades recognized the discovery as a useful human-interest story for promoting scientific work and collecting.4 Naturally mummified remains of human corpses discovered in the dry, high-altitude caves of the American Southwest, the skin on their faces pulled tightly back by centuries of quiet preservation, made for especially captivating stories in the print media. Mummies discovered in the Southwest were often wrapped in blankets or adorned with other sacred burial goods. The hair of the mummies, either peeking out from the blankets wrapping their bodies or flowing down from their heads, ranged from dark black to various shades of red and blond—discolored after centuries of solitude in caves or other dry locations that allowed for the preservation of the body. Americans alternatively viewed the mummies with fascination, wonder, and revulsion. Newly scrutinized when collected and placed on public display, the ancient dead discovered in the American West were transformed from curiosity to antiquity and scientific specimen. Despite their apparent utility in understanding history, mummies discovered in North America in the late nineteenth century were most commonly viewed through the lens of the ultimate American qualifier: race. These naturally mummified corpses might have the ability to teach about ancient civilizations, to be sure, but most people who viewed the mummies in this era hoped they might reveal secrets about the racial origin of the modern American Indian. Mummies dramatically captured newspaper headlines and were the subject of important popular museum exhibitions, but their collection was merely one component of a larger project to collect and classify human bones from around the world.

The lengthy New York Times article following the discovery of a new group of mummies from Alaska details the condition of the remains and informs readers that the bodies were scheduled for shipment to Philadelphia, where they were prominently exhibited at the centennial fair the following year.5 The display of the Alaskan mummies at the 1876 world’s fair built on precedents of displaying human remains, but research into nonwhite, ancient, or otherwise unusual bodies was to assume a heretofore unseen centrality; developing alongside the public’s burgeoning understanding of what was represented by human remains was the scientific community’s organized inquiries into comparative racial anatomy and prehistory.

Presented as scientific commodities and tools for solving riddles connected to race and time, human remains briefly assumed great prominence in the American consciousness. Collecting, displaying, and researching human remains became professionalized in several different contexts. Bodies were a significant attraction to popular audiences attending fairs and private museums in the United States in the late nineteenth century. The public read about their discovery in newspapers and works of fiction, and they became eager to view them firsthand. As significant, however, were the growth and organization of collections of human remains in museums—institutions conducting significant amounts of scientific activity—during the same period. Between the 1870s and the end of the century, theories surrounding the notion of race and racial difference came to dominate studies of human remains in the United States. The Alaskan mummies on display in Philadelphia were no exception. These mummies were but a small part of a growing project to define humankind through systematically collecting rare corpses.

When it came to ancient history and, in particular, mummified remains, the Old World seemed to possess vastly superior and more significant relics (for some people, this was read as evidence that underscored notions of cultural and racial superiority). Attempting to satisfy a thirst for the valued relics of the Old World, Americans collected large quantities of both objects and remains through both professional archaeology and private patronage in Europe, Africa, and Asia.6 As the nineteenth century came to a close, discoveries in the American West offered new spaces for professionals and amateurs to hunt for ancient remains. The remains found within or near cliff dwellings came to be defined as distinctly American—set apart from the ancient history of the Old World. Prevailing racism and popular notions of savage, static, and simple American Indians contradicted simultaneous efforts to preserve sophisticated ancient ruins, but most observers were either blind to or willing to accept this incongruity.

Only one year before the lauded mummy discovery by the Alaska Commercial Company, another New York Times piece articulated the popular antipathy toward the antiquities found in North America: “Our people are not much inclined to think of a great antiquity as belonging to the inhabitants of this continent, or to value highly the relics of our extinct human races. The popular contempt for the red Indian, and the knowledge that all which can be preserved of his tools, implements, and weapons, and works of art, form but a poor collection of antiquities, are in part the explanation of this indifference.”7 Running counter to this prevailing racial and cultural bias, however, were impressive new discoveries of previously unknown archaeological treasures. These finds gave rise to an almost frantic race to collect them for museums in the United States. Archaeologists and their sponsoring institutions engaged in political maneuvering and rapid collecting throughout the American Southwest in a complex competition for artifacts.8 Museums sought ancient pottery and baskets from around the world, just as they sought ancient human bodies. Anthropologists, archaeologists, and physical anthropologists often viewed themselves as competing against both time and each other—but looters represented the main threat to building bone collections. Museums feared that the best specimens—those perceived as valuable for unlocking racial secrets through science—were rapidly vanishing. They were willing to take steps to protect them (at least so as to preserve them for future collecting by professionals). The race to collect human remains was on. In the course of the competition, museums variously became rivals, trading partners, and collaborators in efforts to fill bone rooms with remains from around the world.

A CRITICAL JUNCTURE

Events converging in 1879 critically shaped both archaeology and anthropology in the United States. Breakthroughs fueled continued growth in the desire to collect, study, and display bodies over the ensuing decades. Congress authorized the founding of the Bureau of Ethnology (later called the Bureau of American Ethnology, or BAE), and Frederic Putnam published a major volume on the archaeology and ethnology of the American Indians of the American West. At about the same time, Lewis Henry Morgan, then the nation’s best-known anthropologist, was elected president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Morgan’s election to the head of a major scientific organization was a bellwether for anthropology’s growing stature within the broader scientific community. During the same year, the Anthropological Society of Washington and the Archaeological Institute of America both came into existence.9 The confluences marked 1879 as a critical juncture for professional anthropology in the United States.

One year following the election of Lewis Henry Morgan to head the AAAS, he appointed a Swiss explorer and writer named Adolph F. Bandelier to explore the ruins in the American Southwest. Before the expedition, Bandelier briefly visited John Wesley Powell, an internationally recognized scholar and explorer who was familiar with the region following his famed Colorado River expeditions. Powell, who lost an arm in the Civil War, encouraged Bandelier in their meeting to carefully examine the state of newly discovered archaeological monuments in the American West and report back to scientists in Washington, DC. By August 1880, Bandelier traveled west to begin a study of a series of ruins at Pecos, New Mexico. What he found at Pecos was unsettling. Describing his initial reaction to viewing the ancient dwellings, he wrote, “Most … was taken away, chipped into uncouth boxes, and sold, to be scattered everywhere. Not content with this, treasure hunters … have recklessly and ruthlessly disturbed the abodes of the dead.”10 The bones, mummified flesh, and burial goods, naturally preserved over many centuries, now faced haphazard theft and abusive destruction.

The newly founded Archaeological Institute of America expressed concern to officials in Washington, DC, about ancient sites, but such concern resulted in little action. Many people within the federal government simply cast doubt on the idea that all such sites could be protected under federal law.11 Despite a slow start, newly formed professional organizations concerned with promoting archaeological research and protecting antiquities proved to be significant in the movement to preserve archaeological sites in the United States. Central to the growing concern over preserving antiquities was the desire to collect the bodies for science.

By the time the AMM began collecting bodies for studies in comparative anatomy, Samuel George Morton had already amassed sizable personal collections in Philadelphia.12 Morton’s skull collection, obtained through contacts spread around the globe, provided a clear example on which the physicians at the AMM could base their own collections and research.13 Indeed, when the AMM published a catalogue of crania collections, the work was modeled after Morton’s widely read book Crania Americana. The AMM hoped to expand on this research by making its own catalogue available to an even larger number of students and scholars studying comparative racial anatomy around the country. Buttressing ideas with detailed measurements of all aspects of the human skull, scholars were discussing race in what appeared to be an increasingly complex and sophisticated manner.14 The combined work of scholars like Morton and those at the AMM laid the foundation for the rapid expansion of museum collections of human remains in the United States.

Morton was a leading figure in American science during his lifetime. Considered by some scholars to be the intellectual father of physical anthropology, his human crania collections, by 1849, contained the skulls of eight hundred individuals.15 The skulls varied in age, completeness, and origin. Some were stained white due to prolonged exposure in the hot sun, others a deep mahogany brown from the earth they rested in before being disinterred. Morton’s collection, initially organized for pedagogical purposes, eventually enabled him to produce studies supporting the idea that the measurement of cranial capacities helped identify particular races. Each skull, upon its acquisition, was carefully measured, labeled, and delicately placed on a shelf for preservation. In the words of archaeologist David Hurst Thomas, “To Morton, the human skull provided a highway back in time, a way to trace racial differences to their beginning.”16 For Morton, races were unchanging and arose as a result...