![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Congo of the Belgians

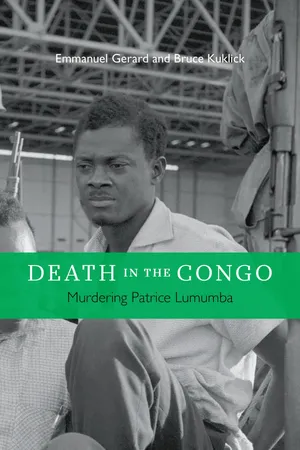

IT IS JANUARY 17, 1961, in the bush of Katanga, almost 10 P.M. Frans Verscheure, the thirty-five-year-old Belgian inspector of police, counsels the local force. In giving orders to muscle Patrice Lumumba’s body into a shallow trench, he has just made himself an accessory to the murder of the prime minister of the Congo. Through force of habit, this trained law enforcement officer glances at his watch to record the moment of the shooting, 9:43 P.M. Then, briefly, the headlights from the automobiles that have lit up the gruesome scene blink out. In the utter darkness, Verscheure hears the wilderness breathing. He feels himself shivering. He is drenched with sweat, and suddenly afraid. His hands are wet and sticky, and although he cannot see, he knows that it is blood. The idea grips him that he is not in his own country. How did he end up with the blood of the Congo’s leading politician on his hands?

Leopold’s Congo

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Portugal divided up much of Africa, but could not figure out how to parcel out the great landmass in the middle of the continent. To prevent significant squabbles, the Europeans awarded the Congo to Leopold II, king of the Belgians, in his own person as head of “the Congo Free State.” It was eventually divided into six immense provinces—Leopoldville on the west coast; Équateur to the north and Orientale to the northeast; Kivu to the east; Kasai in the middle of the country; and Katanga, with a more complex administration, in the far southeast.

Leopold thought that this magnificent land might increase Belgium’s leverage and his prestige. Through this colony, he would unite his tiny nation, divided between Catholics and secularists, haves and have-nots, and speakers of French and of Flemish, a language virtually identical to Dutch. In contrast to a Belgian elite that wanted common ground on the edge of northwest Europe, the Belgian people had little interest in empire, and oversight of this private kingdom—a little less than one-third the size of the present-day United States and almost eighty times larger than Belgium—cost even more than Leopold possessed. The king signed agreements with private shareholders and corporations outside of Belgium, with other Western nations, with wealthy entrepreneurs in Belgium, and with the Belgian government. The Congo was not a domain where rulers somehow linked up with the ruled. Leopold discounted the interests of the Africans and ran the immense area to generate revenue for investors.

The Europeans made the Congo, as they made other African countries, with little regard for prior social or governmental boundaries. The Great Powers swaggered around the continent with no idea of its history or natural features. They ignored ethnic and linguistic frontiers, as well as previous political conditions. In part, attempts to secure advantage over other Europeans, or to conciliate them, determined the new lands. An immense Congo Free State came into being but did not exhibit nationhood as conceived by Europeans and Americans—a single people, a communal sense, a public history, geographical homogeneity, a common culture, shared customs, one language, or unifying military expeditions. It would be wrong to argue that the Congo had an image of its past that Leopold erased in order to dominate. Colonialism instead invented the Belgian Congo, and Leopold discovered the “Congolese” for the benefit of Europeans primarily located in the Belgian capital of Brussels.

Two examples of a lack of cohesion deserve mention. On the Atlantic shore of Africa, the territory known as the Bas-Congo formed a fragment of the old Kongo kingdom. The Europeans partitioned this ancient coastal empire among the French Congo to the north, Leopold’s Congo, and Portuguese Angola to the south. The Congo’s capital city of Leopoldville would grow up here in the 1920s, as well as the province of the same name. But the people in this region often saw their future in a restored Kongo state, and not in the larger but different sort of entity of the whites. From the Congo River on the coast, Leopoldville gave Europe access to the interior. If the Belgians thought of nation building, however, they would not have chosen this headquarters, which lay distant from the heart of Africa.

A different sort of anti-centralism existed in the southeast. There, in Katanga, around what would be the mining center of Elisabethville, Leopold fought off the English. British Rhodesia abutted this portion of the Congo. The English and Belgians scuffled over its mineral wealth. Leopold won a narrow victory in Katanga but yielded a substantial say in the businesses to English interests. Katanga was allocated to the Congo but had a large measure of autonomy and a different status from other areas of Belgian-run Africa. Katanga generated most of the Congo’s profits, and its influential companies—among them the huge mining enterprise Union Minière du Haut Katanga—made their owners rich. These men often looked to nearby English power in the south; they also wanted a direct line to Brussels, not an administration from Leopoldville. As one Belgian diplomat put it, Leopoldville and Elisabethville were as far apart as Paris and Istanbul.1

Over the past century Leopold II has been condemned for twenty years of abominable rule in his “outpost of progress.”2 A series of scandals, an international investigation of atrocities, and growing opposition of the Belgian establishment to the king’s policies concluded in 1908 when he relinquished his fiefdom to the Belgian government. Reformers and politicians reasoned that a colonial government might still engage the populace and assist in lifting it up.

The Belgian Congo

When Belgium took over, the pact between the state and the capitalists persisted, though Brussels made the improvements of an honest shopkeeper. The Europeans had undermined traditional rural existence, although Africans who lived in villages or the inland likely identified only with their ethnic group, and still paid homage to indigenous chiefs. Blacks by the thousands, however, disappeared from the homes of their families, either because of Belgium’s economic demands or because of the attraction of a wider sphere of life. Africans streamed to the cities that were the creation of Europeans—Leopoldville and Elisabethville, at either end of the country; Coquilhatville, Stanleyville, and Luluabourg in the interior; and other municipalities of any size. Workers received living quarters, medical attention, and a social environment conducive, the Belgians thought, to African life. The Europeans built elementary schools to guide the locals to their place in a colony and to low-level jobs. A peculiar protective rule flowered in the middle of the continent, though Belgium ignored political rights and higher education.3 It did not, moreover, encourage European immigration. Although particularly in Katanga and Kivu a few white settlers, colons, called the Congo home, both the official and unofficial masters usually stayed only a number of years, and returned to Belgium for long vacations before a permanent departure.4 Later on, when civic interest glimmered among the Africans, everyone thought of a black polity. In any event, Belgium treated neither blacks nor whites as citizens, if citizenship has anything to do with claims individuals can make on a regime, or with participation in it, or obligations they might owe it. In this sense, the Congo still had no government, only a form of supervision.

Nonetheless, by the early twentieth century, pride in the Congo helped overcome differences in Belgium itself, where the cultural divide had enlarged between a Francophone Walloon south and a mainly Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north. French, an international language, easily predominated in Belgium, but by the first decades of the twentieth century Dutch gained more credibility through a Flemish national movement. The imperialists all had fluent French, the official language in the Congo, although the majority of the Belgians there had spoken Flemish at birth. Yet those whose mother tongue was Flemish rarely had the better jobs and sometimes projected their own feelings of a sort of inferiority onto the locals. The Africans, however, helped to make for a cultural peace among the colonialists. The tensions between the Flemish and the Walloons in the Congo diminished because, as whites (and French speaking), they occupied a different moral space from that of the blacks.5

Social Change

Colonies had evoked distrust from the end of World War I in 1918, but after 1945 the democratic struggle of World War II put the European empires on the ropes, and corroded the Belgian order that had developed from 1910 to 1940. Africans continued to move to the cities, where they lived in ghettos known as cités. These town dwellers felt every day the differences between the lives of the colonizer and colonized, and the intrinsic discrimination of color. The Africans may have traveled from place to place, so they knew about the similar features of cities, and about the large world beyond the villages. In the cités men had conversations about who ran things, although their discussions did not extend beyond municipal boundaries. Certainly Leopoldville’s intrigues and gossip would not tell us much about the rest of the Congo.

In urban areas a new class grew up, the évolués. Education is one key to understanding them. The Roman Catholic Church was one of the few unifying institutions, and delivered widespread primary lessons, as did Protestant missions. The Africans rarely went beyond such classes because colonial authorities structured education to prevent the birth of a privileged group. In theory all the native inhabitants would prosper together; in practice the Europeans afforded only basic tuition, concentrating on the rote observance of rules. The schools trained pupils for bottom-level participation in the workforce, and transmitted values of subservience. The Africans were supposed to acknowledge the guardianship of Belgium and unquestionably accept inferiority. The imperialists discouraged studies that did not fit into their economic needs, and argued that the Africans had no capacity for higher learning.6

In the second quarter of the twentieth century, missions began to offer secondary education. Teachers in the early grades gave more substantial lessons to promising scholars, who gained stature after the war. The Africans spoke many languages, and had some commercial lingua francas, including Kituba, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba. Spoken French inevitably signaled one’s status as an évolué, and ambitious Africans learned the language. They picked up Franco-Belgian culture and made fun of Flemish. The worst thing to call a Belgian in the Congo was Flamand, the French for Fleming. Commentators believed, truly or not, that disaffected Africans would only attack native Flemish-speakers among the whites.7 For more educated blacks, Flemish equated with a secondary language like Lingala. Évolués compared black status in the Congo to Flemish inferiority in Belgium. They also saw the differences between themselves and Africans unschooled in Western ideas as akin to those between French and Flemish speakers in Belgium.

Only exceptional Africans graduated from high school, and only a pitiful few went beyond. In the 1950s a tiny number made it to Belgian universities. Leopoldville and Elisabethville set up their own universities, but they had no rank and hardly any native students. Some Africans, however, had the opportunity for advanced study in religious institutions, and many Africans also had medical training, although the profession of physician was naturally denied them. Yet those who learned French in the upper grades, or spoke French because of religious or technical study, could move in different spheres; so too could those Africans who received just basic lessons but gained expertise in French.

Some Belgians encouraged this new class to believe that if it, for example, gave up polygamy and adopted Western mores, Belgium would grant concessions that would eventuate in equality. This “immatriculation” exemplified the ambiguity of the experience of the évolués, living between two worlds. At home, with knives and forks, they sometimes ate apart from their wives, who sat on the floor using their fingers in a communal bowl. At formal dinners with whites, African men appeared with only one woman, although they might have had multiple wives. Because the women usually did not speak French, they did not understand the denigrating remarks the Belgians made about Africa to their husbands. As a white female put it, the wives lagged “hundreds of years behind … [their husbands] in evolution.”8

In this curious world, where they were both native and foreign, the husbands somehow associated with the oppressor, although they hoped for a time of their own autonomy. They were not entirely comfortable in their own skins. Only the évolués among the Africans had an intellectual understanding of colonialism. They also accepted the supremacy and preeminent worth of Europe. The wealth; the technological ascendancy; the civility; and the globe-spanning bureaucracies convinced these French-speaking natives of the superiority of the West. Perhaps most important, they believed in their status. These Frenchified Africans conceived that they had come up from an inferior way of life. In comparison to Belgium, the Congo lay far down a scale of existence; the évolués must elevate the Congo to the Belgian level. Their conventionality has struck all academics, who have made this kind of analysis standard in appraisals of native elites in colonies.9 Its validity in the Congo needs to be underscored.

Because these Africans also hated the injustice apparent in their lives, they did not just want a country fashioned in a Western model. They must drill the ordinary future citizen into civilization. Critics have called the évolués “bourgeois.” After independence these Africans wanted to replicate the social structure of the Belgian Congo, but with a more generous commitment to a nonsegregated society that they instead of Belgians would administer.

African Nationalism

In the 1950s, the French faced revolutions against their rule in Indochina and Algeria; the English had to deal with the embarrassing apartheid of Rhodesia and a rebellion in Kenya. Soon Britain and France were giving up their colonies, and by the late 1950s Belgium suddenly reckoned with its own loss. From 1958 to 1960, Brussels, in disarray, made concession after concession to the Africans in the Congo. The European view that Africans might take over but would look to the old colonial powers for money and governance had a certain plausibility. The Belgian administration would remain intact, as would political and economic affairs. Brussels hoped more than planned for this outcome. The province of Katanga had for a time just such an agenda: the Africans there obliged Brussels. Such leaky bargains floundered because once independence filled the air, loathing of the Europeans could immediately well up. Moreover, the Europeans panicked about their safety as soon as Belgium admitted the possibility of independence. For everyone, empire lost its legitimacy and Europe its unassailability.

While Belgium’s conception of independence had an unreal aspect, the expectations of the Congo’s youthful politicians had a touch of fantasy. They had not had to fight for their liberty. Political leaders in Brussels barely contested the issue, and seemed simply to throw up their hands in surrender. The Africans perhaps would have had a better chance if they had waged and won a bitter ten-year war. Then they would have forged bonds that prompted cooperation, run an army, outlined political structures, and trained lieutenants in administration.10 Instead, prominent men from various regions of the Congo first met one another in Brussels in 1958, when they traveled to the World’s Fair.

As Africa clamored for an end to empire, the seeds of misfortune were planted. Westerners held up their democracies as the only worthwhile model for civilization, although their practices in the colonies failed to live up to that model. The imper...