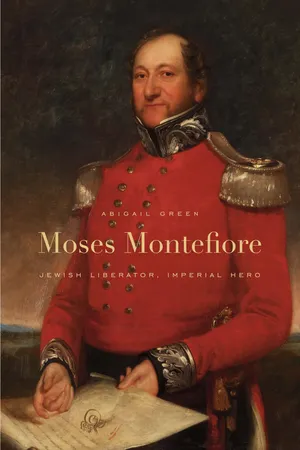

![]()

Chapter 1

Livorno and London

Livorno. 1784. A bustling, thriving port, famed throughout the mercantile world for its dominant role in trade between the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Levant. A magnet for entrepreneurs from East and West. A cosmopolitan, exotic place, where respectable European traders in breeches and wigs rubbed shoulders with their more colorful oriental counterparts, dressed in the turbans and flowing robes of contemporary cliché. The harbor a forest of masts and rigging, its parade of tall ships serviced by an armada of little boats. Sea glittering, seagulls shrieking, the stink of fish and the bleating of livestock; smartly dressed officials taking issue with shabby clerks; porters hollering, sailors shouting. European visitors never failed to comment on the clamor of a hundred tongues and costumes they encountered here: Spaniards, Italians, Germans, Greeks, Turks, Jews, Muscovites, Armenians, and Moors. They traded in everything from silk, cotton, and goat’s hair, through gold, pearls, and precious stones, to leather, tobacco, dried cod, dates, saffron, and caviar.

“How cheerfully I elbowed my way through this riot of nations,” wrote the German poet Ernst Moritz Arndt when he visited Livorno in the 1790s; “such a tumult and chaos of busy, active life as energise this little place … The tone is free and uninhibited, as it is in every lively sea town.”1 Freedom, indeed, was the attraction of Livorno. Men of all nations benefited from the port’s status as a tax haven, but, as the historian Edward Gibbon noted, the real charm of Livorno lay in the fact that “it is actually the people who enjoy complete freedom. Every nation can arrive here and live according to their religion and under the protection of their own laws … This is the veritable land of Canaan for the Jews, who experience here a mildness unknown in the rest of Italy. The interests of commerce have almost silenced the conversionist spirit of the Church of Rome.”2

Religious toleration, in other words, was the secret of Livorno’s success. In the 1590s, at the height of the Inquisition, the Medicis had issued a charter known as la Livornina, which acted as a siren call to the persecuted Jews of Italy and the Iberian Peninsula.3 Everyone in Livorno had a right to absolute freedom and security of goods and person; a right to acquire property of all kinds; and, crucially, a right to live free of inquisition even if they were Jews who had previously lived disguised as Christians in other states. By the 1780s Livorno allowed Jews a say in municipal government—not to mention a host of privileges, ranging from the right to graduate at the University of Pisa to guarantees of fair treatment at law. All this, at a time when Jews elsewhere in Italy were locked up in ghettos, banned from most trades and professions, and stigmatized by wearing the degrading Jewish badge.4 Thanks to la Livornina, the port at Livorno flourished, and Jews came flocking.

In 1752 about a fifth of the major commercial houses in Livorno belonged to Jews, who made up a third of the town’s inhabitants. The 20,000-strong community played such an important role in Livorno’s business life that the whole port reportedly observed Saturday—the Jewish Sabbath—as a day of rest.5 Yet contemporary perceptions of Jewish wealth were exaggerated.6 Roughly half the community survived on poor relief, and only about a third could afford to pay tax at all.7

By the eighteenth century Livorno boasted the largest Jewish community in Italy, and one of the most important in Europe. The Jews of Livorno even spoke their own dialect—Italian, corrupted with Hebrew and Portuguese. By all accounts this dialect was a fair reflection of the community’s mixed heritage: “vivacious, clear and precise … pure for the lowliest expressions … colorful like people’s garments and spicy like their food. It possessed the style of the Bible with something of Spanish pomposity and of Tuscan graciousness. But the use (and misuse) of imagery, proverbs, quaint sayings was still Oriental.”8 In short, the Jews of Livorno typified the mix of cultures that made up the Western Jewish diaspora, known collectively as Sephardim (from the Hebrew word for Spain).

The Sephardim were descended from the Jews of Spain and Portugal, who had flourished under Muslim rule but faced conversion or expulsion as a result of the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Even before the expulsion of 1492, some Spanish Jews converted to Christianity in the face of pogroms and socioeconomic pressures; others took refuge in Portugal, only to be confronted with mass forced conversion in 1497. “New Christians” in both countries remained a distinct social group, specializing in particular economic activities and marrying among themselves. Some were genuine converts; many remained secret Jews. The Inquisition, instituted in the Iberian Peninsula to root out their heresies, only isolated these so-called conversos further. It promoted the growth of a subculture based on secret, family-centered transmission of Judaism, and fostered a strong sense of group identity among those who—tellingly—called themselves “men of the Nation.” Conversos fled all over western Europe and the New World in search of religious freedom and economic opportunity.9 Whenever they felt safe to do so, they jettisoned their “Christian” identity and reentered the Jewish community. Their Iberian background and international connections left them well placed to take advantage of the transformation of the European economy that followed the discovery of the Americas. The thriving western Italian port of Livorno was an obvious destination.

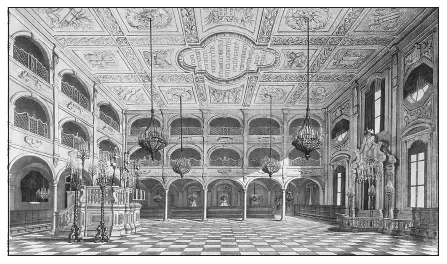

The interior of the synagogue at Livorno around the time of Montefiore’s birth: hand-colored engraving by Ferdinando Fambrino, after Ornabano Roselli, 1793. (By permission of Nicolas Sapieha/Art Resource, New York)

In due course the “men of the Nation” in Livorno were joined by Jews from elsewhere in Italy and by Sephardim from North Africa and the Levant. The latter were also descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain, many of whom took refuge in Morocco and the Ottoman Empire, where they enjoyed the relative toleration of Islam. At first the Iberian exiles looked down on indigenous Jews in these places and established their own communities. With time a rich fusion of the two cultures emerged, in which the Sephardim retained the upper hand. Once again, their Iberian background and connections stood them in good stead, enabling them to mediate both diplomatically and commercially between Christian and Muslim worlds. The Sephardim of the Ottoman Empire played a key role in Mediterranean commerce, while their counterparts in Morocco dominated trade with the West. In the eighteenth century they, too, began to settle in the ports of northwestern Europe, the western Mediterranean, and the Atlantic seaboard. Like the conversos of an earlier generation, they were attracted to Livorno—now a respected center of Jewish learning, a magnet for famous rabbis, and home to one of the most influential Hebrew printing presses in the world.

In Livorno the Jewish “nation” operated to some extent as an autonomous community, but it was also integrated into the life of the town. Jewish merchants thronged the coffeehouses of the elegant Via Ferdinanda, with their gaily painted walls and dazzling display of mirrors.10 Mingling with traders and businessmen of every description, they loitered around the marble-topped tables, making contacts and cutting deals amid the tinkle of silver on fine porcelain. Wealthy Jews were even free to buy villas in the suburbs and surrounding countryside. Most still chose to live among their own in the ten streets that made up the town’s Jewish quarter. Here, as elsewhere in Livorno, the buildings were tall and cheerfully painted. “Four, five, yes some even six, seven stories high,” they blocked out the bright Tuscan sunlight so that the narrow streets below remained cool and shady. In just such a house opposite the synagogue in the Via Reale, a son was born to a young Jewish couple from England on October 24, 1784. Joseph Elias and Rachel Montefiore had been married for barely a year. The boy was their first child, and, in keeping with Sephardi custom, they called him Moses Haim after his paternal grandfather, Moses Vita (Haim) Montefiore—a native of Livorno who had left for England some thirty years earlier.11

The Montefiores were an old Italian Jewish family who had married into the Sephardi diaspora.12 Italian Jews customarily took the name of the town from which they came, and the Montefiores were no exception. Probably they lived at some point in the northern Italian hill town of Montefiore Conca, whence they took the rampant lion and palm tree (fiore) that figure in an early coat of arms.13 They may even have passed through Montefiore dell’Asso, with its charming views of the Adriatic. Either way, by the mid-fifteenth century they had moved on, via Ravenna, to Pesaro, acting as bankers to the dukes of Malatesta in the 1460s. When the popes took over, the Montefiores resettled in Rimini, where they stayed for nearly 150 years. Some then moved to Ancona, where in 1630 one Leone Montefiore gave a curtain, embroidered by his wife Rachel, to hang before the ark in the synagogue.14 By the late seventeenth century, members of the Ancona branch of the Montefiore family had already settled in Livorno.15 In about 1690 a prosperous merchant, Isaac Vita Montefiore, took his nephew Judah from Ancona into business with him. Judah married a member of the wealthy Medina family, and they had four children. The eldest, Moses Vita Montefiore, was born in Livorno in 1712.

After 1715 Livorno faced growing competition from other Mediterranean ports. By the middle years of the century, it was experiencing a structural crisis.16 It is hardly surprising, then, that a young, enterprising Jewish merchant like Moses Vita Montefiore contemplated moving elsewhere. At a time when between half and two-thirds of all ships arriving in Livorno were British, London was the obvious place for him to go.17

Like Livorno, London was a major center for the Sephardi diaspora. Just as la Livornina had attracted the secret Jews of Spain and Portugal, so the readmission of Jews to England in 1656 encouraged conversos to settle in London. Here they could live undisturbed by the discriminatory legal and social structures established in most European countries to constrain and control the Jewish community. But though free, they were not necessarily welcome. In 1753 attempts to facilitate the naturalization process for foreign-born Jewish merchants like Moses Vita provoked loud opposition and revealed deep-rooted fears about the Jewish presence. The motives behind this outcry may have been political and economic, but the prejudices it revealed were religious.18

Perhaps as a result, the Sephardim remained cosmopolitan, with relatives in ports throughout the Mediterranean and even across the Atlantic. Jewish family ties were, quite literally, the lifeblood of early capitalism, and the Western Sephardi diaspora became pioneers of international trade. In an age without a developed banking system, Jewish merchants knew they could rely on their relatives, friends, and business partners overseas. If necessary, they could even appeal for justice in Jewish courts. And so Jewish businessmen played a central role in commerce between London and Livorno, dominating the trade in coral and diamonds that ran between Livorno, London, and India.19

This network made life easier for Moses Vita when he arrived in London. In the early 1740s he began to establish contacts there—no doubt building on his relationship with the fabulously wealthy financier, Sir Solomon de Medina.20 By 1744 Moses Vita had already joined the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue at Bevis Marks. But it is not until 1754 that we find him permanently established in Philpot Lane, Fenchurch Street.21 He had married Esther Racah, the daughter of a Moorish merchant, before leaving Livorno. In 1760 Moses Vita was prosperous enough to be included among the 800 merchants who presented loyal addresses to George III on his accession, on which glorious occasion he was allowed to kiss the king’s hand.

It is likely that Moses Vita’s move to London was part of a wider family strategy. His brother Joseph already lived there, and two more brothers, David and Eliezer, subsequently followed.22 Another cousin, Jeuda di Moise Montefiore, settled briefly in London.23 Almost certainly, the Montefiores of London continued to work closely with the Montefiores of Livorno. In 1755 Moses Vita was active in the coral-diamond trade—possibly in partnership with his brother-in-law Moise Haim Racah, a coral merchant based in Livorno.24 Moses Vita also imported other Italian commodities. Conversely, by 1790 trade with London dominated the affairs of Lazzero Montefiore of Livorno, although he retained business interests in Dublin, Tripoli, Smyrna (Izmir), Sicily, Genoa, and Ancona.25

The two branches of the Montefiore family kept in regular contact. In the next generation their business ties were cemented by several marriages—designed, among other things, to keep the money in the family. Judah Montefiore, the eldest of Moses Vita’s seventeen children, was born and bred in Li...