![]()

1

In 1775 Thomas Reid, a leading light of Scottish philosophy, wrote to the distinguished judge Lord Kames: “I would be glad to know your Lordship’s opinion whether when my brain has lost its original structure, and when some hundred years after the same materials are fabricated so curiously as to become an intelligent being, whether, I say, that being will be me; or, if, two or three such beings should be formed out of my brain; whether they will all be me, and consequently one and the same intelligent being.”1

In 2003 Joe King, an American country and western singer, wrote to me by email: “Hello, my name is Joe King. I am severely disabled, 20 years old. I am 33 inches tall, 40 lbs, 47 broken bones and 6 surgeries. I have been concerned lately that when I die this crippled body might be all I have. My question is. Do u believe consciousness can survive the death of the brain? Is there good scientific evidence for this?”2

We do not know Lord Kames’s answer to Thomas Reid, and I will not tell you, as yet, mine to Joe King. But these questions, even without answers, reveal something of great significance about the role of consciousness in human lives. People are greatly interested in their own personal survival, which they see very much in terms of the continuity of their own consciousness. Consciousness matters. Arguably, it matters more than anything.

The purpose of this book is to build towards an explanation of just what the matter is.

The British psychologist Stuart Sutherland, in his Dictionary of Psychology in 1989, gave a curiously sardonic definition of consciousness. “Consciousness is a fascinating but elusive phenomenon; it is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written about it.”3

You may be surprised—or maybe not—to hear how well this definition has gone down with pundits. A glance at the web (Google, March 2005) shows forty-eight current sites still quoting it with approval. It is clearly a definition that is calculatedly unhelpful. Yet I would say there could be three related reasons why people like it. And each has some bearing on the ways in which personal consciousness contributes to human self-esteem.

One, the definition taps straight into people’s sense of their own metaphysical importance. Consciousness may indeed be an enigma, but at least it is our enigma. If there is something so special and even other-worldly about consciousness, then there is surely something special and other-worldly about us who possess it.

Two, the definition allows people the satisfaction of being insiders with secret knowledge. It may be difficult for us to describe the nature of consciousness to someone else, but it is not at all difficult for us to observe how it works in our own case. Even if we cannot say what it is, nonetheless each of us in the privacy of our own minds knows what it is.

Three, the definition puts scientific inquiry in its place. While people are generally happy enough to have science try to explain the way the material world works, many actually do not want science to explain the workings of the human mind—at any rate not this part of the mind. We fear perhaps that consciousness-explained would be consciousness-diminished. So, when a distinguished psychologist pronounces that there is nothing worth reading on the subject, we can rest assured that consciousness is safe for the time being.

You may find you have a sneaking sympathy with each of these opinions. As to the last, I admit that, although I have been engaged in “consciousness studies” for thirty years, I too feel some perverse pride in the fact that consciousness has held out so far against all attempts to treat it as just one more biological phenomenon. I take comfort in the thought that if and when we do finally get a scientific explanation, it will have at least to be an explanation unlike any other.

“A fascinating but elusive phenomenon.” You can say that again! But do we perhaps mean fascinating because elusive? Would we want it otherwise?

The philosopher Tom Nagel has written, “Certain forms of perplexity—for example, about freedom, knowledge, and the meaning of life—seem to me to embody more insight than any of the supposed solutions to those problems.”4 In a field where so little is agreed or understood, we should expect surprises—and perhaps they will come from the blind-side or even from right behind our backs. Could it be that our very perplexity about consciousness holds the key to why it matters?

It is not always a good idea, in telling a mystery story, to reveal the answer on page four. But I dare say I can tell you just enough to whet your appetite. I shall be arguing that Sutherland’s definition of consciousness, born of perplexity, is actually much closer to the mark than ever he intended. If I am right, the last laugh is going to be on Sutherland himself.

Let’s look at it again. Sutherland suggests it is impossible to specify what consciousness is. But in fact he himself has just alluded to two features that perhaps lie at the very core of what it is: precisely that it is elusive and fascinating.

He suggests it is impossible to specify what consciousness does. But in fact he has just provided a perfect example of what is perhaps one of the things it does best: it challenges people to define and make sense of it and brings them face to face with mystery.

He suggests it is impossible to say why consciousness evolved. But in fact he has just pointed to something that, as it has played out in history, may perhaps have had a major impact on the way in which human life, as the host to consciousness, is valued.

Then, last, he says that nothing worth reading has been written about consciousness. But perhaps he himself, if only he knew it, has just written something quite unexpectedly worth reading about it: namely, this definition.

All these perhapses are tantalizing. But I am going to put them on hold for the time being. There is some other more mundane business (only slightly more mundane) that I want to attend to first. This is to take the generic questions—“What is consciousness? What does it do? Why did it evolve?”—lay them out in good order, and propose a radically new approach to answering them.

There is surely no reason to suppose that answers are impossible. But I would certainly agree with Sutherland that there have been a lot of bad answers, and not enough worth reading has been written. So I want to work—rework—this ground with particular care. What I aim to do is to develop a concept of consciousness which we, as theorists, can do business with, so that we can see more clearly which problems admit of relatively easy solution and which remain hard.

I should warn you that this reworking of basic issues will take most of the pages (if not the idea space) of the book, with the discussion of the value of consciousness coming only at the end. But you need not worry that this means there will not be much of interest in the lead-up.

This book is based on some guest lectures I gave at Harvard University in spring 2004.5 At the start of the first lecture I put up a screen of plain red light and informed the audience I would spend the next three hours discussing what was going on in their minds as they looked at the red screen. This might indeed have seemed to indicate a rather narrow focus. In fact, my host at Harvard, when I explained in advance what I was planning, wrote back suggesting that perhaps I should attempt something a bit “grander.” But, as I hope to show, the discussion that can be raised around a single example of consciousness, “seeing red,” goes naturally from grand to grander.

Let me say something about the style in which the book is written. I would like the experience of reading it to be the next best thing to attending a live lecture. Sadly, I shall not be able to draw you into the argument with interactive color images. But I still want it to sound like a live lecture. So I shall address you as if we were intimates. And, against all the rules of contemporary editing, I shall make free use of capital letters, italics, and irregular punctuation. A reversion to the grammatical manners of the eighteenth century, perhaps. But no bad thing.

![]()

2

The lecture theater has been darkened. And now the projection screen is bathed in bright red light. Something is happening to us as we look at it. The experience of Seeing Red!

What is it like for each of us to be here?

I want to talk you through this, step by step. Phenomenologists, following Husserl, sometimes use the term epoché, to mean an attitude where the subject tries to cast aside all ordinary knowledge and preconceptions so as to focus only on what is. I am not going to attempt a full-scale phenomenological reduction (I have neither the skill nor the ambition). But I do want to discuss a familiar experience in ways that will certainly not be quite the ways that you are used to.

You may think I am putting things the wrong way round. You may think I am being unnecessarily pedantic. But let’s see how it goes, when we approach things from an unusual direction, and on foot.

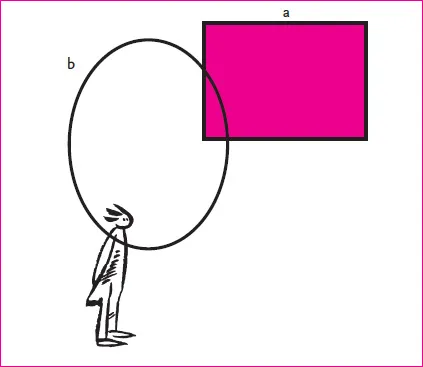

So, here we are looking at the red screen—at any rate, here one of us is [Figure 1]. Let’s call him S. But you should imagine S to be yourself, as I shall imagine him to be me. What are the basic facts about this situation?

To start with, there is a fact about the screen [Figure 1:a]. The screen, illuminated by the projector, is reflecting what we all agree to call “red light”: light with a wavelength around 760 nm, similar to the light that gets reflected from a red object such as a ripe tomato. The screen, in short, is colored red. This, we can say, is an objective fact, which could be confirmed by a physical measuring instrument such as a photometer. It is also an impersonal fact. It does not depend on any person’s interest or involvement with it. Indeed, this fact about the screen would be the same if we all left the room.

But neither you nor I have left the room. S is here, looking at the screen. And, because S is here, there is now an interesting fact about him [Figure 1:b]. S is doing whatever it amounts to for a person to “see red”—doing it, presumably, somewhere in his brain. This fact about S is also an objective fact. There is every reason to suppose it too could be confirmed by a physical measuring instrument—if not with present technology, then soon enough. What is happening in S’s brain is presumably similar to what happens in the brain of any other person who sees red, and its particular signature should be detectable in a high resolution brain scan.

1

However, this fact about S is a personal fact, because it does of course depend on his being here, with his eyes open. It is his seeing red. But being personal is only the beginning of what makes this fact remarkable. Far more important is that this fact belongs, among all the facts of the world, to a very special class: namely the class of objective facts that are also subjective facts.

S is indeed the subject of the experience of seeing red. Which means to say S is the what of what exactly? Being the subject of a visual experience is a complex, layered phenomenon, whose components are not easy to sort out.

There is the story told of an Oxford philosopher who gave lectures one term on “What do we see?” He began hopefully with the idea that we see colors, but he abandoned it in the third week and argued that we see things. But that would not do either, and by the end of term he admitted ruefully, “I’m damned if I know what we do see.”1

Many theorists, before and since, have tried to get a better fix on things than this. In the last hundred years there have been huge advances in the technical sophistication with which psychologists and neuroscientists approach the study of “seeing.” Yet the fa...