- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

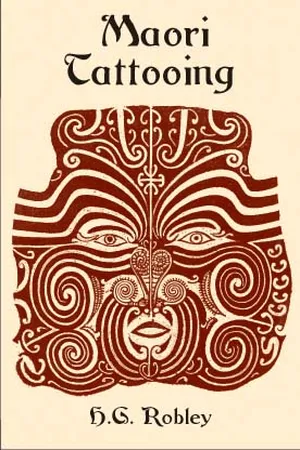

Maori Tattooing

About this book

Originally published in 1896, this classic of ethnography was assembled by a skilled illustrator who first encountered Maori tattoo art during his military service in New Zealand. Maori tattooing (moko) consists of a complex design of marks, made in ink and incised into the skin, that communicate the bearer's genealogy, tribal affiliation, and spirituality. This well-illustrated volume summarizes all previous accounts of moko and encompasses many of Robley's own observations. He relates how moko first became known to Europeans and discusses the distinctions between men and women's moko, patterns and designs, moko in legend and song, and the practice of mokomokai: the preservation of the heads of Maori ancestors. Features 180 black-and-white illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Maori Tattooing by H. G. Robley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

MOKO

MOKO AND MOKOMOKAI

CHAPTER I

HOW MOKO FIRST BECAME KNOWN TO EUROPEANS

HISTORY may yet have more to tell us about the Maoris, but the earliest record of them we have is in the journal of the celebrated traveller Abel Tasman. His visit to New Zealand in December, 1642, was very short, and it ended in bloodshed. But Tasman and the artist who accompanied him, though they record much of the personal appearance of the Maori, make no mention of tattooing. We can hardly suppose that this remarkable feature escaped their observation, since the figure, complexion, hair, and dress are all described; and the conclusion is that in Tasman’s days moko or tattooing did not exist. The Maori has only legends and oral traditions to account for his presence in New Zealand and for his customs such as moko. Maori tradition sheds little light on the origin of this custom. There is no reference in song or chant to help the investigator; and the most that can be done is to compare the observations of navigators with the latest knowledge. In this way we learn something of its rudiments, of its early simplicity, of its later richness and more perfect design, and ultimately of its decay. After a long gap of one hundred and twenty-seven years, we come upon the next mention of the Maori in history; and during that space of time nothing is known of New Zealand. Not until Captain Cook, the great navigator, visited these Islands in 1769 was anything more known. Captain Cook and the Endeavour returned to England in June, 1771, and then it was that the subject of this book became known. The treasures he brought back from the Southern Hemisphere and the drawings and journals he made will be referred to presently. In his time moko was much used in New Zealand. Native tradition has it that their first settlers used to mark their faces for battle with charcoal, and that the lines on the face thus made were the beginnings of the tattoo. To save the trouble of this constantly painting their warlike decorations on the face, the lines were made permanent. Hence arose the practice of carving the face, and the body with dyed incisions. The Reverend Mr. Taylor (an accepted authority on matters relating to the natives of New Zealand) is of opinion that moko or tattooing originated otherwise; and he assumes that the chiefs being of a lighter race and having to fight side by side with slaves of darker hues darkened their faces in order to appear of the same race. These two methods of accounting for the origin of moko are not inconsistent, and both may have had their share in bringing about the results which it is proposed to consider. No reliable evidence whatever exists as to the nature, meaning, extent, or elaboration of primitive moko. But the fact need not diminish its interest.

The term tattoo is not known in New Zealand; and the name given to the decorative marks in question, though elsewhere so called, is in New Zealand moko. The subject, it is true, exercised almost a fascination for the great navigator Captain Cook, who practically rediscovered New Zealand after it had first been visited (as already narrated) in 1642 by Tasman; and to Captain Cook we owe the first full and faithful description of moko, for he gave to it the full force of his unrivalled powers of observation. So important are his comments and notes on the subject that I shall refer to them at some length in the course of this chapter. For the moment I will digress to deal with early historical mention of markings of this nature. Herodotus appears to refer to it as being customary among the Thracians, where he says: “ To have punctures on their skin is with them a mark of nobility ; to be without these is a testimony of mean descent.” This remark suggests a curious analogy between the ancient Thracian noble and the modern Maori chief. Plutarch says that the Thracians of his time made tattoo marks on their wives to avenge the death of Orpheus whom they had murdered in Mœnad fury while celebrating the mysteries of Bacchus. And it is not a little remarkable that a custom should be at one time a punishment to the female sex, when it was or had been an ornament to the other.

There are other references to the custom, and these all tend to show how widely diffused it was. It is, for instance, evidently alluded to (together with the practice of wounding the body to show mourning) in Leviticus (chap. xix). At the twenty-eighth verse we read: “ Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you.” It is reasonable to suppose that both injunctions were directed against a practice common amongst neighbouring nations, which the chosen people according to their usual propensity showed a tendency to imitate. Pliny too states that the dye with which the Britons stained themselves was that of a herb glecstum ; that they introduced the juice with punctures previously made in the skin so as to form permanent delineations of various animals and other objects.

I will now deal with Captain Cook’s remarks.

On Sunday, October 8th, 1769, Captain Cook records that the first native with moko was shot, and notes that one side of the face was tattooed in spiral lines of a regular pattern. The navigator calls the tattooing “ amoco.” In recounting his first voyage, Captain Cook says each separate tribe seemed to have a different custom in regard to tattooing; for those in some canoes seemed to be covered with the marking ; while those in other canoes showed scarcely a stain except on the lips, which were black in all cases. He says : “ The bodies and faces are marked with black stains they call amoco—broad spirals on each buttock —the thighs of many were almost entirely black, the faces of the old men are almost covered. By adding to the tattooing they grow old and honourable at the same time.”

And again : “ The marks in general are spirals drawn with great nicety and even elegance. One side corresponds with the other. The marks in the body resemble the foliage in old chased ornaments, convolutions of filigree work, but in these they have such a luxury of forms that of a hundred which at first appeared exactly the same no two were formed alike on close examination,”

And in the course of his first voyage he describes some of the New Zealanders as having their thighs stained entirely black, with the exception only of a few narrow lines, “ so that at first sight they appeared to wear striped breeches.“ He observes that the quantity and form of these marks differ widely in different parts of the coast and islands; and that the older men appeared...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- TWO LETTERS.

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- PART I - MOKO

- PART II - MOKOMOKAI

- AUTHORITIES CONSULTED

- INDEX