- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Instructions for His Generals

About this book

The king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, Frederick the Great ranks among eighteenth-century Europe's most enlightened rulers. In addition to abolishing serfdom in his domains and promoting religious tolerance, he was an ardent patron of the arts and an accomplished musician. "Diplomacy without arms," he observed, "is like music without instruments." Frederick's expertise at military matters is reflected in his successful defense of his territory during the Seven Years' War, in which he fought all the great powers of Europe. His brilliant theories on strategy, tactics, and discipline are all explained in this vital text.

"War is not an affair of chance," Frederick asserted, adding that "a great deal of knowledge, study, and meditation is necessary to conduct it well." In this book, he presents the fundamentals of warfare, discussing such timeless considerations as leadership qualities, the value of surprise, and ways to conquer an enemy who possesses superior forces. The soundness of his advice was endorsed by Napoleon himself, who once advised, "Read and re-read the campaigns of Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar . . . and Frederick. This is the only way to become a great captain and to master the secrets of the art of war."

"War is not an affair of chance," Frederick asserted, adding that "a great deal of knowledge, study, and meditation is necessary to conduct it well." In this book, he presents the fundamentals of warfare, discussing such timeless considerations as leadership qualities, the value of surprise, and ways to conquer an enemy who possesses superior forces. The soundness of his advice was endorsed by Napoleon himself, who once advised, "Read and re-read the campaigns of Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar . . . and Frederick. This is the only way to become a great captain and to master the secrets of the art of war."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

FREDERICK the Great, King of Prussia, was the founder of modern Germany. When he became King of Prussia it was a small state, in two parts, and of minor importance among the great powers of Europe. During his reign the population increased from 2,240,000 to 6,000,000, and the territory was increased by nearly thirty thousand square miles.

He fought all the great powers of Europe in the Seven Years’ War and successfully defended the national territory.

Although he gained no new lands during this war his success against the overwhelming coalition of his enemies made him a great man of his time and the soldier whom all other soldiers in Europe were to imitate. Frederick’s upbuilding of Prussia determined whether the many small German states eventually were to group themselves around Prussia or around Austria. The expansion of Prussia was continued by Bismarck.

Frederick the Great, or Frederick II, was the grandson of Frederick I, the first King of Prussia. His family The Hohenzollcrns of Brandenburg, was founded by the Margrave Frederick, who began to rule in Brandenburg in 1415.

Successively the monarchs of the line and the years of their reigns and lives were:

1701-13, Frederick I; 1657-1713.

1713-40, Frederick William I, son of the above; 1688-1740.

1740-86, Frederick II, the Great; son of the above; 1712-1786.

1786-97, Frederick William II, nephew of the above; 1744-1797-

1797-1840, Frederick William III, son of above; 1770-1840.

1840-61, Frederick William IV, son of above; 1795-1861.

1861-1888, William I, brother of above; 1797-1888.

1888, March-June, Frederick III, son of above; 1831-1888.

1888-1918, William II, brother of above; 1859-1941.

Judgments of Frederick’s qualities and merits, aside from those which bear upon his firmly-based renown as a military genius, differ widely amongst historians. The range of opinion runs from the extreme provided by Carlyle’s unstinted praise and admiration, which he found it impossible to express adequately in less than the seven volumes of his Frederick the Great, and which consumed thirteen years of his study and time, to that of another critic who roundly condemned the Prussian monarch as “a canonized scoundrel.”

Washington, Franklin and other American patriots of the Revolutionary era openly admired him. When he died Jefferson commented upon his death as an “European disaster” and as an event that “affected the whole world.” Washington welcomed Baron Steuben, and his assistance as drillmaster and tactician, as one of Frederick’s soldiers.

These Americans had reason to feel kindly toward Frederick on score of the service which he undoubtedly rendered the rebellious colonies during the dark winter of Valley Forge, 1777-8. German soldiers from Hesse and Ansbach had been hired by the British for service in America. Frederick who was outspoken against Germans being sent from their native states to fight across seas, refused permission for a considerable body of German mercenaries to pass through Prussian territory to ports of embarkation. Troops that left Anspach in September, 1777, did not reach New York until October, 1778.

Frederick Hampered Howe

To quote from Frederick Kapp’s Frederick the Great and the United States, Leipsic, 1871: “Washington was suffering all the hardships of his winter quarters at Valley Forge from December, 1777 to June, 1778. His weak force could not withstand a vigorous attack by Howe, but when Howe It irned of Frederick’s prohibition of the passage of troops through Prussian territory he knew that that meant cutting off the prospects of any reinforcements. It was not the few men delayed in their journey that hampered Howe as much as the uncertainty about the coming of future German reinforcements. Frederick’s policy was worth to Washington as much as an alliance, for it gave him time and helped to change the fortunes of war.”

But, as Kapp explains, here “without really wishing to do so, Frederick rendered a real service to the young republic.” Frederick was playing a double game. For the time, he was at odds with England. But later, when he needed England’s help against Austria in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778-9) he did authorize George the Third’s hired soldiers to proceed to America, by way of Prussia. He refused to recognize, in advance of the complete triumph of the colonists, the government of the rebels or to receive officially any of its representatives.

After the Revolution the popularity in America of Frederick was attested by number of inns with signs bearing the legend “The King of Prussia.” In Puritan New England and among the Germans of Pennsylvania and New York he was highly regarded as leader of Protestant resistance to Catholic aggression. Evidence is that Frederick never thought of anything but the interest of Prussia in the struggle between England and the American colonies.

One exploded legend is that, in token of his respect and admiration for Washington, he sent the American commander-in-chief a sword fashioned by a Prussian armorer. What happened was that a presentation sword was made by a German who commissioned his son to deliver it to Washington. The son left it in pawn to a Philadelphia tavern for thirty dollars. Friends of Washington redeemed it and it finally reached the General’s hands.

Frederick’s father, Frederick William, brought him up with extreme rigor in the hope that he would become a hardy soldier and “acquire thrift and frugality.” To his father’s disgust he showed no interest in military affairs and devoted his time to literature and music. He was so harshly treated by his father that he resolved to escape to England and take refuge there. He was helped by two friends, Lieutenant Katte and Lieutenant Keith. The plan was discovered, and the Crown Prince was arrested, deprived of his rank, tried by court-martial and imprisoned in the fortress of Kustrin. Keith escaped, but Katte was captured, tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. The King changed the sentence and Frederick was forced to watch his friend beheaded.

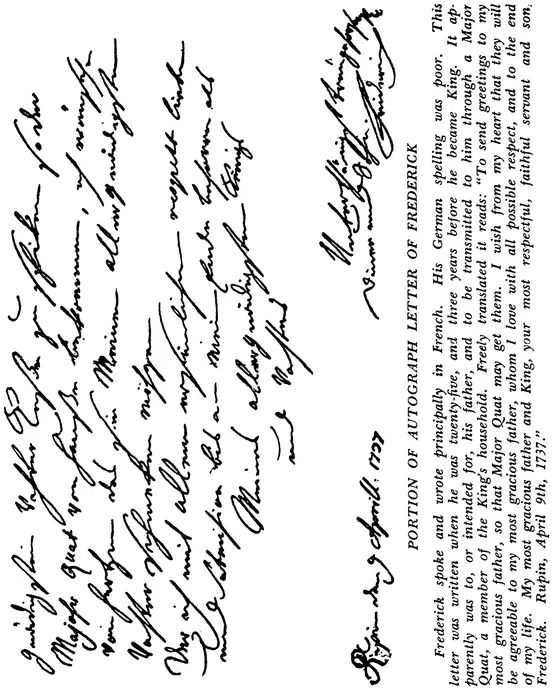

PORTION OF AUTOGRAPH LETTER OF FREDERICK

Frederick spohe and wrote principally in French. His Greman spelling was poor This letter was written when he was twenty-five, and three years before he became king. It apparently was to ,or intended for, his father, and to be transmitted to him through a Major Q uat, a member of the king’s household. Freely trnaslated it reads: "To send greetings they will be agreeable to my most gracious father, whom I love with all possibe respect, and to the end of my life. My most gracious father and King, your most respectful, faithful servant and son, Frederick. Rupin, April 9th, 1737."

Early Victories

While still restricted he was put to work in the auditing office of the war department checking invoices, payrolls, etc. He was allowed to appear in uniform a year later. He became King May 31, 1740, on the death of his father. He seized Silesia from Austria and gained a victory at Mollwitz, April 10, 1741. At this battle he fled from the field under the impression that it had been lost as a result of a furious charge of Austrian cavalry—a mistake which gave rise to a reputation that he lacked of personal courage.

He gained a second victory at Caslau on May 17, 1742, the war ending in the peace of Breslau and the cession of Silesia by Austria. He captured Prague in 1744, but was forced to retreat. In 1745 he won a series of victories and concluded the peace of Dresden, which for a second time assured him possession of Silesia.

Between this time and the commencement of the Seven Years War in 1756, he devoted himself to building up his kingdom. He restored the Academy of Sciences, encouraged agriculture, extended the canal system, drained and dyked the marshes of Oderbruch, stimulated manufactures and increased his army to 160,000 men. He worked arduously all his life, rising habitually at four or five o’clock in the morning and busying himself until midnight. He was economical in the conduct of his personal and state affairs and was scorned and lampooned for this. His economy was not understood in that age of glittering and useless royalty.

The Seven Years’ War ended with the status quo established, but it was, in effect, a great victory. From this time on he devoted his energies to reconstitution of the devastated kingdom. Taxes were remitted for a time to the provinces that had suffered most. Army horses were distributed among the farmers and treasury funds were used to rebuild devastated cities. When he died August 17, 1786, he left an army of 200,000 men and 70,000,000 thalers in the treasury.

Frederick for his time, was a liberal, allowing freedom of press and speech and permitting publication of books and cartoons that derided and lampooned him. Riding along the Jäger Strasse one day he saw a crowd. “See what it is,” he said to his groom. “They have something posted up about Your Majesty,” said the groom, returning. Riding forward, Frederick saw a caricature of himself: “The King in very melancholy guise,” (Preuss as translated by Carlyle), “seated on a stool, a coffee mill between his knees, diligently grinding with one hand and with the other picking up any bean that might have fallen. ‘Hang it lower,’ said the King, ‘lower that they may not hurt their necks about it.’ ” The crowd cheered him as he rode slowly away.

He was deeply interested in the administration of justice and called himself “the advocate of the poor.” It has been a fashion among recent writers to judge Frederick the Great harshly on the grounds of his diplomatic duplicity and the severity of his punishments in the army. But there is something to be said on the other side of that situation. He successfully played the game of deception common to all monarchs in his time. Like all the rest of them, he was intent on adding to his domain. Punishment was severe in the Prussian army, but so was it in all other armies. In the French army pillaging and desertion were punishable by death, whereas in the Prussian army flogging was the prescribed penalty for these crimes. Flogging was given up in the French revolutionary army, but it continued longer in the English army than it did in Germany. It was not until 1813 that flogging was abolished in the American army.

Saxe Gave Guidance

Saxe1, the French marshal, gained his successes in battles of position; he did not live long enough to take advantage of the mobility which his cadence gave to armies. Frederick was to profit by use of the new mobility of masses as Napoleon did later. He was the peer in this respect before Napoleon. He regularly marched his armies at a rate of twenty kilometers a day during periods of two, three and four weeks.

Armies of his time were more numerous, but not so well coordinated as formerly. Increases in numbers attenuated the personal tie between men and their commanders. Lines were thinner and fronts were extended, reducing control. This was the state in which Frederick found European tactics. At the same time his army was more perfect in details, thanks to the work of his father, and he spent more time on strategy.

Prussian soldiers, through constant drill, were able to load and fire their muskets twice as rapidly as their opponents. At the same time, they charged much more rapidly than the enemy and thus gained a further advantage in avoiding the enemy’s fire. Until his enemies learned from him, these advantages helped greatly in his victories.

Frederick’s tactics were based on mobility. This was especially favorable to him because the heavy, slow-moving battalions of his enemies lacked it. In his early years Frederick agreed with Saxe in his belief on the uselessness of fire in attack. Initially, and renewed from year to year, he ordered the soldiers to carry their guns on their shoulders in the attack and to fire as little as possible. But in 1758, he commenced to write that “to attack the enemy without procuring oneself the advantage of superior, or at least equal fire, is to fight against an armed troop with clubs, and this is impossible.” Ten years later, in his Military Testament, he wrote: “Battles are won by superiority of fire.” A decisive word, remarks Captain J. Colin, which marks a new era of combat.

Frederick was a sincere admirer of Saxe in his lifetime and his true testamentary executor. His writings advocate only the offensive, always, in every situation, in the whole of the operations as well as on the field of battle, even in the presence of a superior enemy.

“With such ardor,” writes Capt. Colin, “how does he operate when he makes contact with the adversary? Not an immediate battle, but a long, drawn out jockeying for position. This was a characteristic of operations from ancient times until Frederick. Far from the enemy they forced the pace, but as soon as they approached they beat about, using days, weeks, and months before deciding to fight. Either side could refuse battle because they could get away while the other was arranging his lines.” Frederick carried the operations of ancient war to the highest degree of perfection they ever attained.

Drill Not War

Among the innovations to be attributed to Frederick are: The division of armies so that they could march in a number of columns with less fatigue; the use of flank marches; the oblique order, a practical method of envelopment with the armies of his time; the lightening of the cavalry; increased mobility of artillery and the development of horse artillery; increase in the number of howitzers.

It has been one of the misfortunes of armies that Frederick’s great reputation led to slavish imitation of the forms of the Prussian military system. Young officers from England and France attended the reviews at Potsdam and thought all the secrets of Frederick’s success lay in Prussian drill, Prussian uniforms, and the spit-and-polish tradition. They were unable to distinguish the symbol from the substance in the Prussian army.

Drill was mistaken for the art of war although Frederick never so interpreted it. He “laughed in his sleeve,” says Napoleon, “at the parades of Potsdam when he perceived young officers, French, English, and Austrian, so infatuated with the maneuver of the oblique order, which was fit for nothing except to gain a few adjutant-majors a reputation.” (Quoted by Col. E. M. Lloyd, A Reviezu of the History of Infantry.)

Napoleon ranked Frederick the Great with Caesar, Hannibal, Turenne, and Prince Eugene. What distinguished him above all other generals, Napoleon thought, was his extraordinary audacity. Frederick’s fame was quickly eclipsed by that of Napoleon himself. The result has been that his battles have not been truly appreciated nor is there even in English any good analytical account of them. Guibert, in his Essai General de Tactique, was an admitted expounder of Frederick the Great’s methods, just as Jomini later was to be of Napoleon’s. Guibert influenced Napoleon profoundly. The introduction of a permanent divisional organization into the French army by the Duke of Broglie in 1759 made possible the new advances in mobility and rapid deployment of which Napoleon was to take such great advantage.

The Instruction of Frederick the Great for his Generals was written in 1747 following an illness. It is a remarkable book for a Prince, aged 35. It was revised in 1748 under the title of General Principles of War. One copy of it was sent to his successor to the throne in 1748 with a request enclosed that it should be shown to no one. In January, 1753, an edition of fifty copies was printed and sent to a list of officers whom the King considered models of their profession. A cabinet order enjo...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- I - Frederick’s Instructions, 1747

- II - Projects of Campaign

- III - Defense To Offense

- IV - Subsistence and Commissary

- V - Importance of Camps

- VI - Study of Enemy Country

- VII - Detachments; How and Why Made

- VIII - Talents of a General

- IX - Ruses, Strategems, Spies

- X - Different Countries; Precautions

- XI - Kinds of Marches

- XII - River Crossings

- XIII - Surprise of Cities

- XIV - Attack and Defense; Fortified Places

- XV - Battles and Surprises

- XVI - Attack on Entrenchments

- XVII - Defeating Enemy With Unequal Force

- XVIII - Defense of Positions

- XIX - Battle in Open Field

- XX - Pursuit and After Battle

- XXI - How and Why to Accept Battle

- XXII - Hazards and Misfortunes of War

- XXIII - Cavalry and Infantry Maneuvers

- XXIV - Winter Quarters

- XXV - Winter Campaigns

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Instructions for His Generals by Frederick the Great, Thomas R. Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.