![]()

PART I

Fluid Mechanics Review

![]()

Chapter 1

Rotating Fluid Phenomena

Many areas of engineering and science involve the rotation of various objects; in science the object sometimes is the earth; in engineering it might be a turbine rotor or a space vehicle. In most cases the object also involves the rotation of internal or external fluids. Sometimes a rotating fluid is the principal phenomena of interest; at other times the fluid is merely an unwanted participant in the motion. In either event, success or failure of the analysis can depend critically on understanding and predicting rotating fluid phenomena.

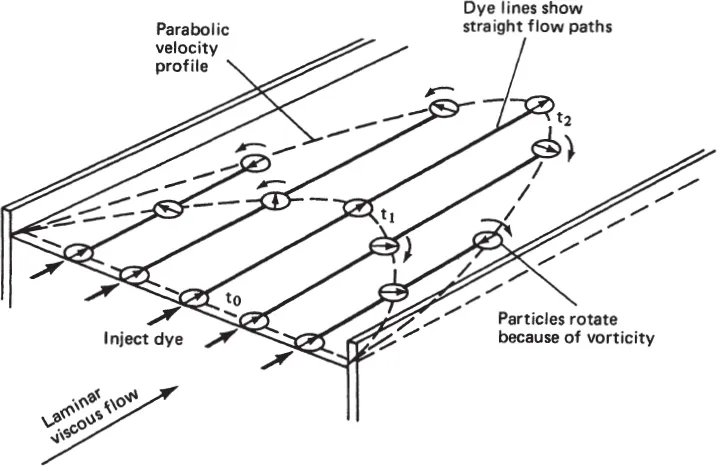

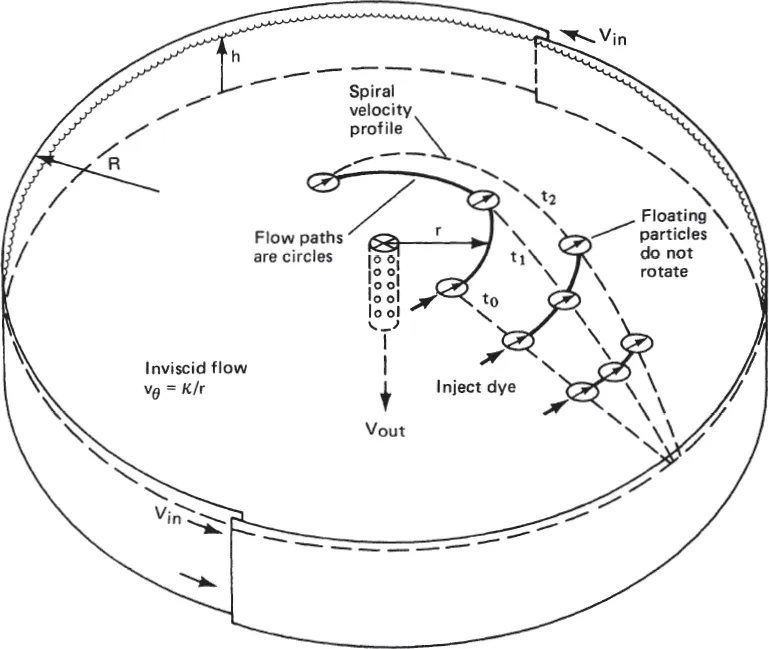

The basic theory of fluid rotation and vorticity distinguishes between vorticity and curved (e.g., circular) translation of fluid elements. Figure 1.1 illustrates smooth uniform flow of a viscous liquid in a channel. This laminar flow, when fully developed, has a parabolic velocity distribution. Ink or dye slowly injected in the flow would move in straight lines indicating straight streamlines (fluid motion). However, small objects placed in the flow would also rotate as they move, indicating that the flow has vorticity, i.e., the infinitesimal fluid elements rotate as they translate along straight lines. Figure 1.2 illustrates a flow field called an inviscid vortex where all fluid elements move in circular paths. However, small objects here would not rotate, indicating a fluid that is not rotating, merely translating in circular paths. The two flows illustrate two extremes, one that has straight pathlines but fluid element rotation, and the second that has circular pathlines but fluid elements which do not rotate. Viscosity in the first flow produces the fluid element rotation called vorticity, which is absent in the second flow. Rotation, vorticity, and circulation are described and quantified in Chapter 8. Figure 1.3 shows a smoke ring. Its motion is often modelled as a toroidal inviscid vortex. Any cross section through the toroid is approximately an inviscid vortex as in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.4 shows water in a cylinder. In the left photograph, both the cylinder and the water are stationary, and all the colored water, slightly less dense than the clear water, is in the top one-eighth of the cylinder. In the right photograph, the cylinder has been impulsively accelerated to a constant angular velocity, and the water is gradually being "spun up" to the angular velocity of the cylinder. Liquid spin-up is achieved about 1% by viscous interaction at the cylinder side walls and about 99% by a viscous secondary flow at the cylinder bottom. Centrifugal force inside this very thin (almost invisible) spinning bottom boundary layer moves clear water outward and then up along the outside cylinder wall. Colored water in the interior is drawn downward until all the water will be pumped outward through the very thin, bottom boundary layer. In this experiment, a 2% buoyancy of the colored water is opposing the pumping action and causes the boundary between the clear and colored water to be tapered rather than cylindrical. More complex rotating fluid phenomena, such as internal waves and vortex stretching, are involved during a reverse spin-down process.

Figure 1.1: Laminar flow of a viscous fluid in a straight channel moves along straight streamlines. The fluid elements rotate, however, because of viscosity. The streamlines can be observed by injecting ink into the flow, and the rotation (vorticity) can be observed by the rotation of small corks placed in the flow.

Rotating masses of fluid exhibit other unusual properties. Figure 1.5 shows the difference between flow patterns created by suddenly dumping a quantity of similar density colored water into nonrotating water, (top two photographs), and flow patterns created by the same act, but using rotating water as shown in the bottom two photographs. Typical turbulent eddies are generated in the nonrotating water. Such random motions are not possible in a rotating liquid; instead, permissible flows have a distinctly two-dimensional property as shown in the photographs.

Figure 1.2: An inviscid vortex flow has circular streamlines. In a perfect such flow, corks would move in circular paths but would not rotate, exactly the reverse of Figure 1.1. This experiment can only be approximated in the laboratory because fluid viscosity will introduce some vorticity, the fluid surface will not be flat, and a secondary flow along the bottom will pump liquid radially inward. A very small Vin and Vout is needed in the laboratory to maintain the flow.

Rotating fluid theory helps explain important application areas in engineering and science. These include many subtle fluid-structure interactions that produce vorticity and secondary flows. For example, when a viscous fluid moves through a bend in a pipe or channel, differences in velocity and pressure between the central portion and the boundary layers near solid surfaces induce secondary flows similar to those on the bottom surface of the cylinder in Figure 1.4. These secondary flows cause energy losses in engineering applications and erosion when the channel is a river bed. Figure 1.6 shows a typical result. Bottom secondary flows and sediment move transversely from the outside of a bend toward the inside of that bend. Any slight departure from straight line motion becomes more and more pronounced, gradually reaching the condition shown in Figure 1.6. If a flood condition occurs, the river may overflow the meandering channel and erode a nearly straight channel to...