- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

`A very impressive and comprehensive story on terrorism . . . enormously valuable.`—Brian Crozier, former director of the Institute for the Study of Conflict, London

A compulsively readable analysis of modern terrorism, this brilliant, vital work by a noted expert on terrorism and guerrilla warfare describes the nature of terrorist organizations and events and analyzes the changing nature and evolution of unconventional political warfare.

From the genesis of the Great Terror initiated by Robespierre over 200 years ago, to the Black Panthers, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the mass terrorism of Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, this absorbing work offers unsurpassed insight into seemingly irrational acts of violence and murder. The author, who was born in Russia and as a youth only narrowly escaped being a victim of terrorism, does a superb job of helping readers to understand the causes and nature of terrorism, and how terrorists use intimidation, violence, and bloodshed to threaten the stability of society.

A compulsively readable analysis of modern terrorism, this brilliant, vital work by a noted expert on terrorism and guerrilla warfare describes the nature of terrorist organizations and events and analyzes the changing nature and evolution of unconventional political warfare.

From the genesis of the Great Terror initiated by Robespierre over 200 years ago, to the Black Panthers, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the mass terrorism of Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, this absorbing work offers unsurpassed insight into seemingly irrational acts of violence and murder. The author, who was born in Russia and as a youth only narrowly escaped being a victim of terrorism, does a superb job of helping readers to understand the causes and nature of terrorism, and how terrorists use intimidation, violence, and bloodshed to threaten the stability of society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Terrorism by Albert Parry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Nature of Terrorism

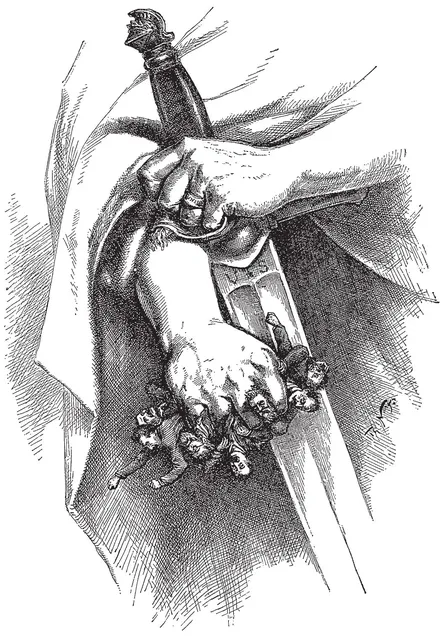

“Liberty is not Anarchy”

(Cartoon by Thomas Nast—Public Affairs Press)

1

Violence: Genesis of Terror

Not every violence is political terror, but every political terror is violence. Be it caused by Robespierre or Bakunin or the old West European anarchists or Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Hitler, or today’s urban guerrillas the world over, terror is essentially a ferocious violence of humans against humans.

As the inhumanity of man to man, violence has woven its fearsome thread from caveman to technological man. “Homo homini lupus est” (Man to man is wolf), declared Titus Maccius Plautus, the Roman playwright (c. 254-184 B.C.) in his comedy Asinaria (The Asses). Violence seethes in many a person, family, clan, tribe, nation, state—even though, according to Thomas Hobbes, writing in The Leviathan (1651), the state was evolved by man to check his savageness.

For thousands of years in the West, where Robespierre, Marx, and Hitler would be born and where modern terrorism would have its beginnings, torture as a form of violence was part of the legal codes of many states, sometimes as a technique used in forcing confessions, sometimes as sheer punishment. Ancient Greek law and notably Roman law prescribed torture in detail, stipulating when, how, and on whom it was to be used. The very word “torture” comes from the Latin torquere, to twist. Since, in later centuries, Roman law was the source of the codes of so many European nations, the legal framework of those nations included torture as both logical and necessary. But even those national codes that did not owe much, if any, historical debt to Roman law had their own indigenous practices of torture and harsh death. Certainly neither the English phrase, “rack and ruin,” nor the Russian word pytka—interrogation by torture—came from Rome.

In Western lands, torture for God’s greater glory was widespread and lasted for centuries under the Inquisition. In 1252, Pope Innocent IV, by his bull Ad extirpanda, authorized torture of the accused to obtain the victims’ confessions and the names of additional heretics. Unable to bear the horrible pain, many shrieked their confessions, and—guilty or innocent—were executed publicly. Many were burned at the stake, among them John Huss in 1415 and Joan of Arc in 1431. In the late fifteenth century, under Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada, brutalities were ingenious and numerous—some 2,000 humans were put to the torch. In later times, as both state and Church mitigated certain forms of violence, torture was officially limited and at last nominally abolished.

But in fact, officially or not, torture persisted. The alleged enlightenment of the eighteenth century did not stop the West European, American, and Arab traders and owners of African slaves from inflicting pain and injury on their human property. Ostensibly it was a required form of discipline, usually involving whipping and starving, or a function of necessity, involving suffocation in dungeons or in the holds of ships or drowning at sea—in storms captains would lighten their vessels by casting their slaves overboard. But actually the blacks were often the victims of sheer sadism. In Latin America the Spanish grandees and soldiers intimidated reluctant Indians into submission by pulling their rebel leaders apart: their limbs were tied to two horses that were then prodded in different directions.

The progressive nineteenth century saw the King of the Belgians introduce Western culture into the Congo with the aid of unspeakable atrocities visited upon the natives. Our own twentieth century has brought two significant changes in the methods of torture: the use of electrical and other technological advances, and the development of various forms of psychological torment—devised by the secret police of Communist Russia, Nazi Germany, and other assorted totalitarian regimes of several continents.

The geographical area in which Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin would institute and maintain slave camps and make their own contributions to the evolution of political terrorism also has a singular heritage of violence.

The Scythians, warlike nomads who spoke an Indo-Iranian language and roamed the plains north and east of the Black and Caspian Seas from the ninth to the third centuries B.C. had as their main deity the god of war. Represented by a sword struck into the ground, it was wetted by the blood of prisoners. The Scythians also drank this blood. Like American Indians, they scalped their captives and attached the scalps to their bridle reins as signs of prowess. They often skinned their prisoners alive, believing that human skin collected in this manner was superior to animal hide.

Yet in time the Scythians were paid in their own coin. In the thirteenth century A.D., the Mongols of Genghis Khan overran the last remaining domains of the descendants of the Scythians in Central Asia. They hauled the conquered populace into the fields, where they placed the captives on the ground face down—men, women, and children in separate neat rows. The Mongols then marched along the rows, methodically cutting off all heads. After a few days they would suddenly return to flush out and kill the survivors who had escaped the first roundup.

In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, Tamerlane, who claimed descent from Genghis Khan, assembled pyramids of human heads, each pyramid containing skulls by the scores of thousands. Although such pyramids had been piled up before by the Maliks of Herat and other conquerors of earlier centuries, Tamerlane’s were on a far vaster scale. Yet these and other victors on occasion did keep at least some of their captives as live property—a dubious form of mercy that took man thousands of years to evolve.

Conquerors sweeping out of the East to plague and plunder the West also displayed this questionable progress. In the fourth and fifth centuries the Huns, in their invasions of Central and Western Europe, not only massacred men and their families but also took slaves. The Vandals in the fifth century, in addition to murdering multitudes and destroying precious works of art, kept captives, if not statues, as their property.

When, early in his career, Temuchin, the future Genghis Khan, led his Mongols against the neighboring Tatars, he consolidated his victory by destroying nearly all of that people’s males, but spared boys if they were no taller than a cartwheel’s linchpin. All women and surviving children were enslaved, and even the name of the victim people was adopted by the victors, who were from then on known as both Mongols and Tatars .

After the initial butchery of the conquered Russians in the mid-thirteenth century, the Mongol-Tatars made prisoner-taking a form of taxation. As the era’s doleful song lamented:

If a man has no money,

The Tatar takes his child;

Should there be no child,

The Tatar takes the wife;

If there is no wife to lose,

The Tatar takes the man himself.

The Tatar takes his child;

Should there be no child,

The Tatar takes the wife;

If there is no wife to lose,

The Tatar takes the man himself.

During ensuing wars and raids the Tatars would return with many roped and chained Russians. Once safely out of the reach of Muscovite troops, the raiders would sort out their human booty. A French witness of one such episode in the depredations by the Crimean Tatars in 1664 recorded that before their departure for their Crimean homes the victors went through their 20,000 captives and “cut the throats of all those who were over 60 years of age and thus unfit for labor. Men of 40 were spared for the galleys, young boys for delights, and girls and women for procreation and eventual sale.”1

It has been thought by some historians that until the Mongol-Tatar invasion the Russians were a mild folk, not given to cruelty against one another or even toward foes, that they must have learned their atrocious ways from those Tatar intruders and usurpers. Yet we know that long before the hordes from Asia struck at them, the Russians used savage and unusual punishment of their own during both peace and war. Their slaves, serfs, and freedmen were subject to ingenious, blood-chilling cruelties. One method was to bury prisoners and criminals (among the latter, women accused of adultery) up to their heads. This left the bodies to unbearable pressures of the earth and the heads exposed to sun or frost as well as to the gnawing by hungry dogs.

But the oppressed, when rising, were also cruel. When serfs and Cossacks rebelled against the Tsar and his nobles, terrible vengeance was theirs. In 1670, Stenka (Stephen) Razin’s capture of Astrakhan and his “great slaughter and robbery” of many noblemen, foreign officers, and mariners was observed by an English chronicler:

[Prince Ivan Prozorovsky, Astrakhan’s governor] was... made to goe up that high square Steeple, which stands in the midst of the Castle of Astracan, for a Beacon to direct those that Navigate the Caspian Sea... From this Steeple the said Governor was cast down head-long.... The Brother of the Governor, and many Noblemen and others, that would not come to him [Razin], he put to the sword, as also many Dutch and other Officers, and some Holland Mariners.... The Churches, Cloisters, and the Houses of the richest Citizens were plunder’d; the Writings of the Chancery burnt, the Czar’s Treasure of the Kingdom of Astracan carried away, many Merchants strangers, being there at that time, as Persians, Indians, Turks, Arminians, and others, were put to death... both the Sons of the Governour he caused to be hung by the Legs upon the Walls of the Town, and to be taken down again, putting one of them, after much torture, to death, and causing the other to be beaten half dead.... His [the governor’s] Lady and Daughters he delivered to the Soldiers, his Companions, to take them for their wives, or, if they pleased, to abuse them.2

As Razin marched west and north to take other cities along the Volga, peasants’ uprisings preceded his army; serfs killed off their landlords with their entire families, putting their severed heads in sacks and bringing them to Razin, flinging the bloody bags at the leader’s feet as they petitioned to join him.

One hundred years later, in the revolt of 1773-75 led by another Cossack of the Don, Yemelian Pugachev, as one after another Tsarist fortress in the steppes fell, officers, along with landlords and priests and visiting foreigners, were tortured and slain. Anyone wearing Western clothes was doomed. A German botanist was captured near one estate as he was peacefully gathering flowers and grasses. The gleeful rebels stripped off his clothes and impaled him. Whole families of nobles were hanged on their mansion gates. Parents and children were suspended in rows according to age. Decades later, in The Captain’s Daughter, a tale of those times, Russia’s great writer Alexander Pushkin, while delineating Pugachev’s character in faintly sympathetic strokes but harshly deploring the atrocities for which he was responsible, presented a thought to be remembered and repeated for generations: “God save us from witnessing a Russian rebellion, senseless and ruthless!”

Each of the rebel leaders was defeated: Razin in the 1670s by the troops of Tsar Alexis, and Pugachev in the 1770s by the army of Empress Catherine II. After being apprehended, both Razin and Pugachev were tortured and executed. Their followers were knouted and branded, many tongues and ears were cut off, and thousands were hanged. Rafts filled with limp bodies dangling from gallows were sent down the Volga and other rivers. These, as intended, left a lasting impression on the miserable masses.

From the heritage of the Mongol-Tatar enslavers and torturers, carried on and improved upon by such native insurgents as Razin and Pugachev, derives much of the terror of that giant bloody upheaval, the Russian Revolution. And from that Revolution stems much of the political terror in the world today.

II

East or West, what is the cause of violence, of the destructiveness of human beings?

Hannah Arendt remarks that given “the enormous role violence has always placed in human affairs” it may seem surprising that writers on history and politics have devoted to it so little of the close study it surely deserves. But on second thought it is not so surprising. As Arendt says, “This shows to what an extent violence and its arbitrariness were taken for granted and therefore neglected; no one questions or examines what is obvious to all.”3 Yet if writers on history and politics have not pondered it sufficiently, novelists and psychologists have.

While declaring that his fellow Russians were pure and would yet bring their light from the East to the benighted Western world, Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote of the universal violence in man’s nature. In 1866, in The Gambler, he reflected: “Savage, limitless power—even over a fly—this is a kind of enjoyment. Man is a despot by nature; he loves to be the torturer.” In 1879, two years before his death, after a tumultuous life of suffering and of witnessing the torment of others, he said: “There is much good in man, but also so much evil that, were it to surface, we would find it difficult to breathe anywhere in the world.” In part this was so because man was not only a sadist but also a masochist. Man wanted to be tortured, he derived a keen delight from being whipped. Man’s joy is in the whip (we read in The Gambler), “when the knout scourges his back and tears his flesh to pieces.”

In more recent times Sigmund Freud wrote and taught that aggression was a basic instinct that could be destructive not only of others, but also of the self. It was, he declared, part of a pattern of man’s natural instincts, some positive and others not. To Eros, or the life instinct, Freud counterpoised Thanatos, or the death drive. In this dichotomy Freud saw the principal drama of man’s subconscious, of man’s whole being.

In an elaboration of Freud’s theory, Carl Jung believed that even if aggressiveness does not emerge in us as individuals, it is still an inborn part of us that can and does surface when we form a collective, particularly when we form a mob. Jung states:

We are blissfully unconscious of those forces because they never, or almost never, appear in our personal dealings and under ordinary circumstances. But if, on the other hand, people crowd together and form a mob, then the dynamics of the collective man are set free—beasts or demons which lie dormant in every person till he is part of a mob. Man in the crowd is unconsciously lowered to an inferior moral and intellectual level, to that level which is always there, below the threshold of consciousness, ready to break forth as soon as it is stimulated through the formation of a crowd.4

In her brief but meaningful book On Violence, Arendt pays particular heed to the interconnection of violence and power. She convincingly argues that power—the gaining and the exercise of it—is all-important in the many kinds of violence we know, including those of greed, passion, crime, riots, revolution, and terrorism. Violence: to many, its other name is power.

Often, however, it is the very realization of a person’s powerlessness that leads him to violence. If a human cannot be powerful enough to be creative, he becomes destructive. In The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, Erich Fromm writes: “If man cannot create anything or make a dent in anything or anybody, if he cannot break out of the prison of his total narcissism, he can escape the unbearable sense of powerlessness and nothingness only by affirming himself in the act of destruction of the life that he is unable to create.”5

Then, paradoxically, violence itself can become creative, or, in Fromm’s words, “Destruction is the creative, self-transcending act of the hopeless and crippled, the revenge of unlived life upon itself.”

But this elevation of violence into something creative or otherwise positive is surely subject to doubt. Such praise causes damage to mankind. Whether or not political violence has been manifested as a lust for power or as a reaction to the fear and frustration of powerlessness, it has, while being clearly excessive, been unduly—and harmfully—glorified, romanticized, and legalized. This worship and legalization of violence is a tradition that has inspired terrorists and enabled them in part to justify their actions undeservedly.

III

Is all aggressiveness, be it individual or collective, necessarily bad? Konrad Lorenz argues that aggression, although definitely something we are born with, need not be all negative. (Here, to an extent, he agrees with Fromm.) Lorenz says that humans, unlike animals, manifest their aggression too indiscriminately. Animals fight to kill in order to preserve their specific group’s territory and thus their food and females, to survive and reproduce. Humans kill not only for these goals but also for many counterproductive reasons.

For this failing, Lorenz blames thousands of years of inventive, human civilization, which have derailed man’s natural instinct of moderate aggression and have caused him to become a mass murderer. As being particularly pernicious, Lorenz cites technological developments that are increasing the power and the remoteness of the slayer. It is the evolution of human ingenuity, so terrifyingly represented by the nuclear bomb, that debases the survival value of aggression, that has brought the hatred and mutual destruction so characteristic of our era.6

But B. F. Skinner, the behaviorist, asserts there is no such phenomenon as man’s inherent nature, bad or good. He believ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Epigraph

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- PART I - The Nature of Terrorism

- PART II - History

- PART III - Modern Times

- PART IV - Terror with a Difference

- APPENDIX - The Lethal Record

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index