![]()

1

No Center, No Object, Just Networks: Expanded Internet Art

People aren’t sure about what an image or object is anymore. They’re not sure how things are fixed or where they belong. If something can be a jpeg online, what is it when you print it out and put it up in a gallery? … For me, the only way out of this research problem is to proliferate those nodes, to extend them further and further out, so that what you get is a dispersed work. There is no center, and there is no object to look at as such; there’s just this nodal network that you’re in the midst of. You’re in this expanded field of sculpture that exists between the material and immaterial realms. That possibility for producing work seems really exciting.

Mark Leckey from “Art Stigmergy”

Kaleidoscope, Summer 2011

Artist Mark Leckey reveals a situation that is becoming commonplace in contemporary art practice. Internet-based art practices seem to be particularly responsive to the decentered quality Leckey describes, especially as the internet drifts far beyond the screen and filters into every aspect of our lives with this process accelerated by advances such as faster bandwidth, smartphones, and social media. Contemporary internet art is no longer determined solely by its existence online; rather, contemporary artists are making more art about informational culture using various methods of both online and offline means, which results in a type of expanded internet art. For artworks that volley between networked data files and physical materials, the internet is not seen as the sole platform for the production of a work but instead as a crucial nexus around which to research, assemble, transmit, and present data, both online and offline. Art in this manifestation is not viewed as hermetic but instead as a continuously multiple element that exists within a distributed system. In this sense, there is a keen attention to the dispersion and parcelization of the art object over a network. In artist interviews, essays, conference panels, and artist statements, several terms have come up in an attempt to describe this move—“internet aware,” “post-internet,” “dispersion,” to name a few. This chapter reviews these conversations in an effort to capture and contextualize this shift within contemporary art.

The concept of expansion will be a recurring theme throughout all of these discussions. Expansion is described not as an outward movement from a fixed essence but rather, in light of data’s dispersed nature, a continual becoming. Internet art can be viewed as the ultimate form of an expanded artwork, drawing from the definition of expansion as “the action or process of spreading out or unfolding; the state of being spread out or unfolded.”1 This quality is not accidental but rather a product of informational dynamics or what theorist Tiziana Terranova calls an “informational milieu,” which guides the movement and flow of information. The production and transmission of digital information is progressively reorienting our environment, a fact that is apparent all around, in everything from car design to ATM machines. This chapter argues that artists are creating work that is intentionally diffuse, distributed, and “expanded” as a product of an informational milieu. Through this method of working, artists are not just internalizing these conditions but thematizing them.

Defining internet art

The logical first step in this conversation is to address the question, what is internet art? The term has its origins in the 1990s with the term “net.art,” which has been used to categorize the practice of the first wave of artists working online in the mid-1990s. Artist Alexei Shulgin recalls on a post to the mailing list, nettime, which was an important forum for artists experimenting with work online in the 1990s, that the term originated with another artist Vuk Cosic in 1995. Receiving a message from an anonymous mailer containing a file that could not be opened by Cosic’s software, Cosic found the message turned up scrambled ASCII characters that contained the term “net.art” among the garbled letters. Shulgin sees the term “net.art” as itself a readymade, enabled by the unique conditions of the internet.2

Shulgin and Cosic were part of a global scene of artists experimenting with the internet, a conversation and community fostered by online discussion forums and exhibition venues like the mailing list nettime (1995), the BBS service THE THING (1991), the mailing list, website, and platform Rhizome (1996), the mailing list Syndicate (1995), the e-mail-based performance art mailing list 7–11 (1998) and the online art platform äda’web (1994). Early net.art evolved outside of the framework of the traditional art world, which provided a sense of unfiltered, fresh experimentation to the projects and conversations that occurred on these platforms and around them. As art historian and media theorist Dieter Daniels has noted, one thing that was very unique to artists working online in the 1990s as opposed to other eras of media art, like video art in the 1970s, was that it was not an intervention into an already existent form but rather a “simultaneous development and testing of a new medium and its mutual influence on technological, social and aesthetic functions of electronic networks.”3 As the internet became a widespread, globalized network and more readily accessible in the 1990s to a broader public, the websites and projects created by net.artists explored the political and cultural significance of that arena, helping shape net culture itself.

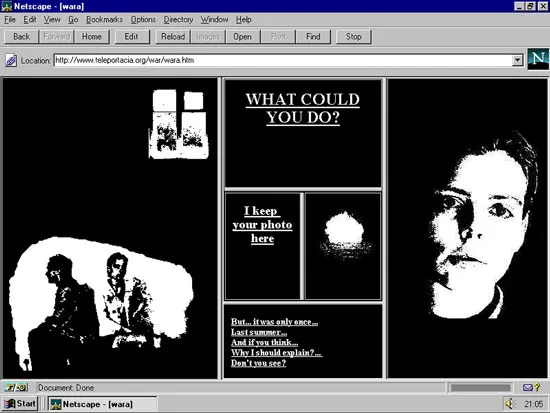

Art historian and curator Rachel Greene identified six main net art formats between 1993 and 1996: e-mail, websites, graphics, audio, video, and animation. All of these often appeared in combination with one another, pushing the capacity of the browser as a space for artistic expression.4 For example, one of the most celebrated works of net.art from this period is Olia Lialina’s My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (1996). The work follows the story of two lovers who reunite after a war through a nonlinear narrative followed through nested frames containing animated gifs, hyperlinks, and linked images. Realizing an emotionally powerful narrative through html and gifs, the story unravels through the links selected by the visitor, and eventually ending on a mosaic of empty black frames. The work was very much native to the web, but its use of narrative and image adopted an almost cinematic quality (see Figure 1.1).5

Figure 1.1 Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, 1996.

http://www.teleportacia.org/war.

One of the most well-known exhibitions exploring net.art during this period was net_condition curated by Peter Weibel for ZKM Center for Art and Media in Germany. The exhibition was one part of a larger project titled Art and Global Media, which was a “networked, multimedia and multilocal” event involving many iterations from October 1998 through February 2000 in collaboration with several partners in Barcelona, Graz, Karlsruhe, and Tokyo. This umbrella project aimed to bring greater awareness to contemporary new media’s ability to “change and construct reality” and took place primarily in the media space in which they commented on, whether that space was a billboard, or on television, or in a newspaper, or online.6 The net_condition portion of Art and Global Media was also distributed, presented online as well as in the ZKM galleries and partner sites located at the steirischer herbst in Graz, the ICC Intercommunication Center in Tokyo, and the MECAD Media Centre d’Art i Disseny in Barcelona during the fall of 1999. The net_condition exhibition, which included over 100 individual artworks, was the first comprehensive overview of international net art and, in some respects, served as a capstone to many years of art production online. In addition, Weibel was very clear that he hoped the artworks in exhibition would bring attention to the social conditions enabled by the internet. In his accompanying essay, he specifically identifies “dislocation,” “nonlocality,” and interactivity as key aspects that differentiated net.art from previous forms of media art. Freed from the gallery or the museum context, online artworks can be viewed by the visitor anywhere at anytime. According to Weibel, this flexibility in both time and space for the artwork was something quite novel. Furthermore, net.art is interactive in nature and requires the viewer to engage by scrolling, clicking, etc. This enacts a feedback system between the image within the virtual space of the computer and the real space of the viewer.7 Through Weibel’s framing of the net_condition exhibition, we see that net.art is a practice-based online in a “virtual” space, whose flexibility, dislocation, and interactivity relate a new means of socially impactful communication and connection.

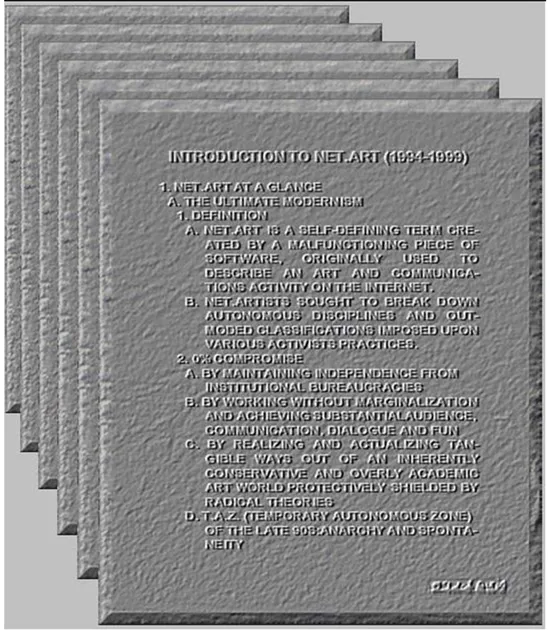

net_condition was staged in a time when the term “net.art” seemed to be on the wane. One project included in the exhibition, Alexei Shulgin and Natalie Bookchin’s Introduction to net.art (1997), humorously captures the ennui surrounding the term at this moment (See Figure 1.2). As a text document online, and later realized in chiseled stone slabs in the gallery, the work is directed to the uninitiated viewer, and it presents in an outline format what net.art is, how it is made, how a net.artist can be successful, and what the world will look like after net.art. Although the tone is at times tongue in cheek, where the authors provide details such as the exact amount of memory on a computer necessary to become a net.artist, there is an element of seriousness regarding net.art’s political and activist thrust. Under “Net.art at a Glance” the subheader “0% compromise” cites net.art’s basis in the web as an element that allows the work to operate outside of the traditional art world with a substantial audience and independence.8 Introduction to net.art reveals the context and attitude of a time with a touch of melancholy and skepticism about the future of net.art after institutional and media interest, which for some limited the anarchic and playful aspects of net.art.

Figure 1.2 Alexei Shulgin and Natalie Bookchin, Introduction to net.art, 1997.

http://rhizome.org/artbase/artwork/48530/.

Unlike net.art, the term “internet art” is broader and more encompassing. Writers Rachel Greene’s Internet Art and Julian Stallabrass’s Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce tackle their decision to name these kinds of practices “internet art” in the first few pages of their books and both settle on “internet art” to describe artists working online. For Stallabrass, the struggle with terminology is associated with the quickly changing terrain of the internet, “To write about art on the Internet is to try to fix in words a highly unstable and protean phenomenon. This art is bound inextricably to the development of the Internet itself, riding the torrent of furious technological progress.”9 Greene sees this instability as a defining feature, stating, “By virtue of its constantly diminishing and replenishing medium and tools … internet art is intertwined with issues of access to technology and decentralization, production and consumption, and demonstrates how media spheres increasingly function as public space.”10 For both authors, “internet art” signals all work made online, spanning e-mail, online software applications (like Java applets), code, and individual websites, which all rely on the internet to function. Both Greene’s and Stallabrass’s accounts reveal the tension between the instability of the internet as a complex, evolving environment and a notion of medium identified through its stable, quantifiable qualities.

Josephine Bosma, in her collection of essays about internet art Nettitudes: Let’s Talk Net Art, similarly points to the change inherent to the internet in her answer to the enduring question, “what is internet art?” In her estimation, “net art is based in or on Internet cultures. These are in constant flux.”11 Bosma’s definition envisions internet art as an art responsive to internet cultures, one that can take any form, online and offline. Writing in the late 1990s and early 2000s, both Stallabrass and Greene focus on internet artworks presented on a computer screen over a network in their discussions, and their specific examples follow suit. However Bosma, writing in the mid-to-late 2000s, accepts that internet cultures can and do exist outside of stationary desktop computers.

Bosma turns to ...