![]()

1

“They Were Just Like Everyone Else”

One of Gale Huntington’s favorite activities is driving his guests around the island of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, at speeds never exceeding thirty-five miles an hour, and pointing out spots of historical interest. Gale’s memory of the region goes back over eighty years, when coasting vessels crowded Vineyard Haven harbor and whale ships were still seen in New Bedford. He knows as much about the Island as anyone alive today. In the course of one of these jaunts “up-Island,” in late October 1978, Gale pointed out Jedidiah’s house to me.1 “He was a good neighbor,” said Gale, “He used to fish and farm some. He was one of the best dory men on the Island, and that was pretty good, considering he had only one hand.”

“What happened to the other one?” I asked.

“Lost it in a mowing machine accident when he was a teenager.” As an afterthought, he added, “He was deaf and dumb too.”2

“Because of the accident?” I asked.

“Oh no,” said Gale, “he was born that way.”

On the way back to Vineyard Haven, as we puttered down a sandy ridge overlooking a wide expanse of Vineyard Sound, Gale glanced at a weatherbeaten clapboard house on the left and said, “Jedidiah’s brother lived there.” Nathaniel had owned a large dairy farm. “And,” said Gale, putting his foot on the brakes by way of emphasis, “he was considered a very wealthy man—at least by Chilmark standards. Come to think of it, he was deaf and dumb too.”

I wondered aloud why both brothers had been born deaf. Gale said no one had ever known why; perhaps the deafness was inherited. I suggested that it might have been caused by disease. But Gale didn’t think so, because there were so many deaf people up-Island, and they were all related. There had been deaf Vineyarders as long as anyone could remember. The last one died in the early 1950s.

“How many deaf people were there?” I asked.

“Oh,” said Gale, “I can remember six right offhand, no, seven.”

“How many people lived in town here then?”

“Maybe two hundred,” Gale replied, “maybe two hundred fifty. Not more than that.”

I remarked that that seemed to be a very large number of deaf people in such a small community. Gale seemed surprised but added that he too had occasionally been struck by the fact that there were so many deaf people. No one else in town had treated this as unusual, however, so he had thought little more about it.

One rainy afternoon on my next trip to Martha’s Vineyard, I sat down with Gale and tried to figure out the genealogies of the deaf Islanders whom he remembered. I thought that the deafness up-Island might have been the result of an inherited trait for deafness, and I wanted to do some research on the topic.

Gale’s knowledge of Island history and genealogy was extensive. He sat in his living room smoking a few of those cigarettes expressly forbidden by his doctor and taking more than a few sips of his favorite New England rum as he reminisced about times long past and friends who had been dead half a century or more. As we talked, he recalled from his childhood three or four additional deaf people. When he was a boy in the early 1900s, ten deaf people lived in the town of Chilmark alone.

I had already spent a good part of the afternoon copying down various genealogies before I thought to ask Gale what the hearing people in town had thought of the deaf people.

“Oh,” he said, “they didn’t think anything about them, they were just like everyone else.”

“But how did people communicate with them—by writing everything down?”

“No,” said Gale, surprised that I should ask such an obvious question. “You see, everyone here spoke sign language.”

“You mean the deaf people’s families and such?” I inquired.

“Sure,” Gale replied, as he wandered into the kitchen to refill his glass and find some more matches, “and everybody else in town too—I used to speak it, my mother did, everybody.”

• Anthropology and the Disabled

Hereditary disorders in relatively isolated communities have long been known, and geneticists and physical anthropologists have studied a number of examples of recessive deafness in small communities.3 Martha’s Vineyard is one more such case. For over two and a half centuries the population of this island had a strikingly high incidence of hereditary deafness. In the nineteenth century, and presumably earlier, one American in every 5,728 was born deaf, but on the Vineyard the figure was one in every 155.4 In all, I have identified at least seventy-two deaf persons born to Island families over the course of three centuries. At least a dozen more were born to descendants of Vineyarders who had moved off-Island.

In this book I draw on genetics, deaf studies, sociolinguistics, ethnography, and oral and written history to construct an ethnohistory of a genetic disorder. The complex mathematical models are more appropriate for medical genetic and physical anthropology journals and thus will be published elsewhere. Here I concentrate on the history of this genetic trait and on the history of the people who carried it, for the two are inseparable. A genetic disorder does not occur in a vacuum, somehow removed from the lives of the human beings affected by it. How do the affected people function within their society, and how do they perceive their own role in the community?

Traditionally, disabilities have been analyzed primarily in medical terms or, by social scientists, in terms of deviance. In the social science literature, deviance is defined as an attribute that sets the individual apart from the majority of the population, who are assumed to be normal.5 Deafness is considered one of the most severe and widespread of the major disabilities.6 In the United States alone, 14.2 million people have some hearing impairment that is severe enough to interfere with their ability to communicate; of these, 2 million are considered deaf (National Center for Health Statistics 1982).

A deaf person’s greatest problem is not simply that he or she cannot hear but that the lack of hearing is socially isolating. The deaf person’s knowledge and awareness of the larger society are limited because hearing people find it difficult or impossible to communicate with him or her. Even if the deaf person knows sign language, only a very small percentage of the hearing population can speak it and can communicate easily with deaf people. The difficulty in communicating, along with the ignorance and misinformation about deafness that is pervasive in most of the hearing world, combine to cause difficulties in all aspects of life for deaf individuals—in education, employment, community involvement, and civil rights.

On the Vineyard, however, the hearing people were bilingual in English and the Island sign language. This adaptation had more than linguistic significance, for it eliminated the wall that separates most deaf people from the rest of society. How well can deaf people integrate themselves into the community if no communication barriers exist and if everyone is familiar and comfortable with deafness? The evidence from the Island indicates that they are extremely successful at this.

One of the strongest indications that the deaf were completely integrated into all aspects of society is that in all the interviews I conducted, deaf Islanders were never thought of or referred to as a group or as “the deaf.” Every one of the deaf people who is remembered today is thought of as a unique individual.7 When I inquired about “the deaf” or asked informants to list all the deaf people they had known, most could remember only one or two, although many of them had known more than that. I was able to elicit comments about specific individuals only by reading informants a list of all the deaf people known to have lived on the Island. My notes show a good example of this when, in an interview with a woman who is now in her early nineties, I asked, “Do you know anything similar about Isaiah and David?”

“Oh yes!” she replied. “They both were very good fishermen, very good indeed.”

“Weren’t they both deaf?” I prodded.

“Yes, come to think of it, I guess they both were,” she replied. “I’d forgotten about that.”

On the mainland profound deafness is regarded as a true handicap, but I suggest that a handicap is defined by the community in which it appears. Although we can categorize the deaf Vineyarders as disabled, they certainly were not considered to be handicapped. They participated freely in all aspects of life in this Yankee community. They grew up, married, raised their families, and earned their livings in just the same manner as did their hearing relatives, friends, and neighbors. As one older man on the Island remarked, “I didn’t think about the deaf any more than you’d think about anybody with a different voice.”

Perhaps the best description of the status of deaf individuals on the Vineyard was given to me by an island woman in her eighties, when I asked about those who were handicapped by deafness when she was a girl. “Oh,” she said emphatically, “those people weren’t handicapped. They were just deaf.”

• Sources

Because I have taken an ethnohistorical approach to a phenomenon that has usually been consigned to the field of medical genetics, it is important to explain how I gathered my information over the course of four years. After my initial discussion about deafness with Gale Huntington and his wife, I reviewed what had been published on deafness on the Island. Except for one or two articles in local newspapers from the nineteenth century and a handful of scattered references in nineteenth-century publications for the deaf, nothing had been written on this subject.

Written Records I then searched the available published and unpublished records concerning the Island for information about deaf residents. Vineyard records are unusually complete, but only in one or two instances did any of these records note that a person was deaf. With the exception of the federal census, which began to keep records on the number of deaf Americans in 1830, there was no place, and no need, to mention an individual’s deafness on birth, marriage, or death records, land deeds, or tax accounts.8

Oral History Although it seemed that the lack of written information would limit my study of Vineyard deafness, I decided to gather as much from the records as possible. After several expeditions to the Island, I found that one source of informaton—oral history—was consistently useful. The oral historical tradition on Martha’s Vineyard is remarkably strong, largely because the same families lived on the Island for three centuries with very little dislocation. It was not unusual to interview an elderly Islander living in the house where his grandmother or great-grandmother had been born. Families stayed in the same small Island villages and hamlets for two or three centuries. Because of this continuity, the local traditions remained intact, and personalities and events had an immediacy and a contextual framework that would be unusual in a more fluid population.

No individuals with the inherited form of deafness that existed for several centuries on the Island are still alive. To find out about these people, I tried to interview every Vineyarder old enough to remember some of the Island deaf—neighbors, friends, relatives, people who had fished with deaf persons or attended church with them or could recall seeing them at the town meeting or the county fair. I paid particular attention to those people, mostly in their eighties and nineties, who remembered the deaf residents as active members of the community.9 In all, I interviewed more than two hundred Islanders, including some who had moved off-Island. I spent the most time with a core group of about fifty people, all Island elders, whose vast knowledge of Vineyard people and events formed the basis of my research.10 I was able to substantiate much of their oral tradition with written documents, and I have attempted to place it within a theoretical framework; but without the assistance of these Islanders, this book would be little more than a listing of names and dates.

Historians, oral historians, and folklorists have long argued over the relative merits of oral and written records. I tried to anticipate and compensate for many of the potential problems by cross-checking oral and written sources against each other. (For a more detailed discussion of this subject and of some problems I encountered, see Appendix A.)

Only two of the older Islanders declined to be interviewed. At first, however, many people claimed they did not know enough to be helpful. Most informants regarded what they remembered as private memories, family anecdotes, and local gossip; they were intrigued to find that their memories tied in with dozens of other recollections. Often, if I mentioned a name, an informant would say, “Why, I haven’t thought of him in years.” If I mentioned an event that another Islander had told me about, the person would ask, “Where did you ever hear about that? I didn’t think anyone else remembered.”

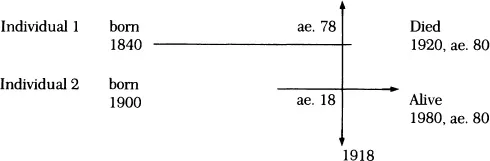

Islanders are acutely aware and justifiably proud of their past. Elderly residents, remembering stories their parents and grandparents told them, created a chain of memories extending back to about 1850, a span of 130 years. The most recent events were more clearly in focus, but the older Islanders were familiar with names, dates, and stories, back to 1850 and were able to place individuals in a social matrix. This time span seems to form the limit on active oral history. A man who was eighty in 1982, for example, would have been a teenager at about the time of the First World War and would have had regular contact with people born seventy or eighty years before. One can visualize the overlap as shown in the figure above. Something that happened in...