![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Jim Twins (February–March 1979)

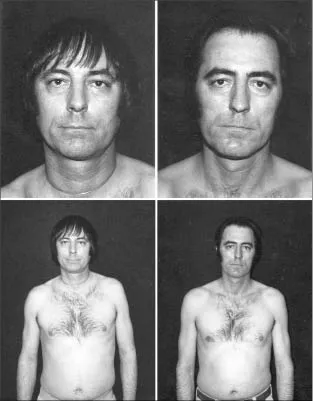

ON FEBRUARY 19, 1979, the Lima News in Ohio reported the reunion of thirty-nine-year-old identical twins Jim Lewis and Jim Springer, separated at four weeks of age (Figure 1-1). The twins, born to an unwed mother, had been placed in the Knoop Children’s Home in Troy, Ohio, and had been adopted separately by two local families. They grew up forty miles apart, Lewis in Lima and Springer in Piqua.1

The couples who adopted the twins were Jess and Sarah Springer, and Ernest and Lucille Lewis. Both families had been told that their child was a twin whose brother had died. The source of this misinformation and the reasons for it have never been determined. The Springers, who adopted two weeks ahead of the Lewises, would have taken both twins had they known both twins survived. In fact, several years later the Lewises adopted identical twin boys, Larry and Gary, even though court officials suggested that they take just one.2 Perhaps the court reasoned that raising one child would be easier for parents than raising two. By then, Lucille Lewis knew that her son’s twin was alive, and she refused to separate another set.

When Lewis was a toddler, his mother visited the Miami City, Ohio, court regarding some adoption matters. A court officer blurted out that the other family had also named their son Jim. Shocked by this information, Lucille waited until her son Jim turned five to tell him he had a twin. Over the years she encouraged him to find his brother, but he hesitated. Then, shortly before his thirty-ninth birthday and for no apparent reason “the time was right.” Lewis asked the Piqua court to contact his twin.

Springer learned that he had a twin when he was eight, but he had accepted the story that his brother had died. Then, at Jim Lewis’s urging, the Piqua court told Jim Springer that his brother was alive and how to contact him. Springer called Lewis and left a message with his call-back telephone number. Lewis returned the call, and the twins met for the first time.

Figure 1-1. The Jim twins: Jim Springer (left) and Jim Lewis. (Photo courtesy Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. Unposed photographs taken in David Lykken’s laboratory.)

Three weeks after they met, Springer served as best man in the ceremony for his twin brother’s third marriage. Newspapers chronicled the twins’ striking similarities, including their first names (Jim), their favorite school subject (math), their dreaded school subject (spelling), their preferred vacation spot (Pas Grille Beach in Florida), their past occupations (law enforcement), their hobbies (carpentry), and their sons’ first names (James Alan and James Allan). The article about them was reprinted in newspapers around the country, including the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Jim and Jim were not the first separated twins to surface in the United States since the publication of a series of case studies in 1949 by Barbara Burks and Anne Roe.3 MZA twins Tony Milasi and Roger Brooks were reunited in 1962, at age twenty-four, after Roger was mistaken for Tony by a busboy in a Miami, Florida pancake house. Their reunion was covered in the press, and a book describing their lives appeared in 1969.4 When the book appeared, Bouchard had just joined the University of Minnesota faculty and Lykken had not begun to study twins.

On February 20, 1979, the day that the Star Tribune article appeared, University of Minnesota psychology graduate student Meg Keyes showed the story to her professor, Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. She had taken Bouchard’s course in individual differences in behavior, a class that included readings about separated twins. A second copy of the Star Tribune article was left in Bouchard’s mailbox by psychology professor Gail Peterson. Peterson appended a note saying, “I thought you would get a kick out of this.”

Meg, now Dr. Keyes of the Minnesota Twin Family Study, remembers that Bouchard was “excited from the get-go—he moved fast getting funds, staff, and tests together.” “I had to find the twins—I thought someone else would go for the Jims, but no one did,” said Bouchard.

Every once in a while, a scientist encounters an unusually fascinating research problem, issue, or situation that is irresistible. Such projects usually involve some degree of risk in terms of time, funding, and reputation, but the process is exhilarating if the topic is right. Few people had the opportunity to compare, firsthand, the behaviors of identical twins reared apart from birth. Bouchard admitted that he had formed a “big plan” in a few hours, but with no money.5

Bouchard telephoned the Associated Press in Cincinnati, Ohio, in an attempt to locate the twins. He told the person on the other end that he was prepared to “beg, borrow and steal” to support this case study. On February 25, 1979, the New York Times ran the front-page story, “Identical Twins Seen as Offering New Clues in a Psychology Study; Searched for Brother.” Bouchard was quoted as saying, “I’m going to beg, borrow and steal and even use some of my own money if I have to. It is important to study them immediately because now that they have gotten together they are, in a sense, contaminating one another.” The New York Times apparently had obtained the story over the Associated Press wire; Bouchard recalls hearing typing on the other end as he spoke, explaining why his words were repeated.

Bouchard’s original letter of invitation sent to Jim Lewis and Jim Springer introduced the investigators and provided an overview of activities the twins would complete. The letter also explained that the project covered airfare, food, lodging, some lost wages, and a modest honorarium to offset miscellaneous expenses. Bouchard also invited each pair to dinner one evening.

The Core Research Team

Bouchard established a core research team consisting of psychologists David T. Lykken (now deceased), Irving I. Gottesman, Auke Tellegen, and psychiatrist Leonard L. Heston (Figures 1-2 and 1-3). Each had heard about the Jim twins directly from Bouchard. At first, Lykken wondered if studying just one pair was worth the trouble, but Bouchard told him, “You are my friend—humor me.”6 Lykken did and became intrigued. Gottesman was immediately interested and suddenly confident that additional pairs could be found.

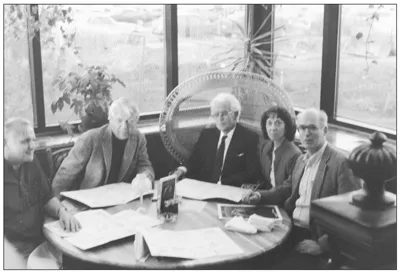

Figure 1-2. Left to right: Leonard L. Heston, David T. Lykken, Niels Juel-Nielsen, Elke D. Eckert, and Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. (Photo courtesy Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. Photograph taken in May 1981 by a waiter in a Minneapolis restaurant. The occasion was the visit by Dr. Niels Juel-Nielsen, who had studied reared-apart twins in Denmark.)

Heston felt that the Jim twins would make an “interesting case that was worth doing,” but he doubted that the work would progress beyond the single-study stage. His views changed once the group had assessed seven or eight pairs, making him aware that the study had “real potential.” Heston was also responsible for inviting University of Minnesota psychiatrist Elke D. Eckert to become part of the core team. Tellegen spoke for both Lykken and himself when he said that both thought studying the Jim twins would be a “one-time opportunity” and that it required sophisticated idiographic methodology—standard psychological procedures were not appropriate for research on just one set. Initially, he and Lykken tried to develop statistical techniques that would replace multiple subjects with multiple observations, but when the sample size grew this proved unnecessary.

The University of Minnesota’s psychology department had a long history of individual differences research, much of it with a behavioral-genetic bent. Therefore, studying development by way of twins reared apart was natural for that time and place. Following Gottesman’s 1957 twin study dissertation, conventional identical-fraternal twin comparisons had been ongoing since 1970 under the direction of David Lykken, who developed the Minnesota Twin Registry between 1983 and 1990. The Minnesota Twin Registry includes information on 901 twin pairs born between 1904 and 1936, 4,307 twin pairs born between 1936 and 1955, and 391 male twin pairs born between 1961 and 1964; see Twin Research 2002. Bouchard called his department’s atmosphere “fabulous—you cannot create it, it must exist.”

Figure 1-3. Left to right: Irving I. Gottesman, Auke Tellegen, and MZA twin Jim Lewis. (Photo courtesy Thomas J. Bouchard Jr. Photograph taken by a media center staff member, March 1979.)

Lykken became Bouchard’s most frequent coauthor—according to Bouchard, “We never really disagreed.” Gottesman was famous for his 1960s twin studies of schizophrenia conducted with James Shields (who conducted the 1962 British reared-apart twin study), and for having administered the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) to adolescent twins. Heston had published a seminal 1966 adoption study of schizophrenia and was the father of identical twin daughters, Barbara and Ardis. Heston and Gottesman had become acquainted in the mid-1960s when Heston joined the Medical Research Council (MRC) Unit in Psychiatric Genetics in London. Gottesman was already there and had encouraged Heston to come.7 Eckert, a specialist in eating disorders, found the idea of reared-apart twins fascinating: “It was a chance to look at genetic and environmental influences on behavior, something I hadn’t studied much.”

Tellegen had recently developed the Differential Personality Questionnaire (now the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire).8 The Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire is an eleven-scale form for assessing individual variation in personality. Tellegen had worked collaboratively with Lykken on psychophysiological twin studies involving more than five hundred pairs. Tellegen also credited a supportive department chair, John (Jack) Darley Sr. for facilitating study of the Jim twins.9 Matt McGue, now Regents Professor in the psychology department at Minnesota, was a graduate student at the time, in charge of setting up the twins’ information processing tasks. “When I came back it was very exciting here. The MISTRA put us on the map.”

Another factor favorable to the study’s success was that the university’s psychology department and medical school were located on the same campus, facilitating assessment of behavioral and health-related traits. For the first time, reared-apart twins were undergoing cardiac, pulmonary, dental, periodontal, ophthalmologic, and endocrinological testing, as well as psychological assessment. Some medical tests, such as the electrocardiogram (ECG), were administered from the beginning; others, such as the periodontal examination, were added later.

The Assessment

Every colleague acknowledged that Bouchard’s extraordinary ability to generate enthusiasm was key to starting the study and keeping it going. When the study began, Bouchard was investigating factors affecting general intelligence and special mental abilities. His 1970s publications included studies of spatial ability, problem-solving strategies, and intelligence testing. He quickly put together a comprehensive assessment schedule that required four days for the twins to complete. The Jim twins and the pairs who followed became the first separated sets to complete psychological, psychophysiological, psychomotor, life stress, and sexual life history protocols; previous reared-apart twin studies focused on general intelligence and personality traits.

The research program could not be completed in four days, so the Jim twins returned to Minnesota five months later. The assessment schedule eventually expanded to fill five full work days, plus one evening and two half-days.

An important activity of the first assessment day was a series of unposed photographs of the twins taken alone, then together. The MZA twins’ typically similar body postures and the DZA twins’ typically dissimilar ones were unexpected findings, suggesting that there is genetic influence on these behaviors. We would also see genetic effects on body movement and gestures suggested by the MZA twins during separate videotaped interviews held later in the week. Bouchard recalls a pair of British women who continually twirled a strand of pearls around their necks as they spoke. Details of all the tests and inventories that were administered are provided in subsequent chapters and in this book’s Web site.

The medical tests began on the first full study day and continued over the next three days. Dr. Naip Tuna, then Director of Electrocardiography and Non-Invasive Cardiology, first learned about the Jim twins from Bouchard. Tuna was “very interested” but uncertain as to the importance of heredity in adult cardiac functioning. “I thought genetics played a greater role in children’s heart disorders,” he admitted. Nevertheless, Tuna was intrigued and assumed the role of primary physician and cardiologist for the study. Eckert and Heston administered the twins’ psychiatric interviews and medical life histories until clinical psychologist Will Grove replaced Heston, who joined the University of Washington in 1990.

Other physicians saw the reared-apart twins as a unique opportunity to conduct research in their own fields. Dr. Michael Till, a pediatric dentist, read about the project in the university’s newspaper, the Minnesota Daily. Till brought the study to the attention of his colleagues in adult dentistry, but there was little interest. He attributes their cool response to patient overloads, heavy teaching responsibilities, and emphasis on restorative dental procedures. But Till was captivated. He contacted Bouchard, whom he did not know at that time, and the addition of a dental component to the project was decided over coffee. Till’s only concern was that the walls of his examining room were decorated for children and the examination chairs were on the small side.

Thanks to my own periodontal problems, a periodontal evaluation was added to the project in 1986. While having my gums probed at the university’s clinic, Dr. Mark Herzberg asked me about my twin research. It was hard to talk, but I managed to describe what we were doing and finding. H...