![]()

I

The Basic Model

![]()

1

Nine Theories of Judicial Behavior

There are many positive (that is, descriptive as distinct from normative) theories of judicial behavior.1 Their primary focus is, as one would expect, on explaining judges’ decisions. The theories are the attitudinal, the strategic, the sociological, the psychological, the economic, the organizational, the pragmatic, the phenomenological, and, of course, what I am calling the legalist theory. All the theories have merit and feed into the theory of decision making that I develop in this book. But all are overstated or incomplete. And missing from the welter of theories—the gap this book endeavors to fill, though in part simply by restating and refining the existing theories—is a cogent, unified, realistic, and appropriately eclectic account of how judges actually arrive at their decisions in nonroutine cases: in short, a positive decision theory of judging.

I begin with the attitudinal theory,2 which claims that judges’ decisions are best explained by the political preferences that they bring to their cases. Most of the studies that try to test the theory infer judges’ political preferences from the political party of the President who appointed them, while recognizing that it is a crude proxy. The emphasis is on federal judges, in particular Supreme Court Justices. State judges are of course not appointed by the President, and sometimes the method of their appointment—for example, by nonpartisan election—makes it difficult to classify them politically.3

Justices and judges appointed by Democratic Presidents are predicted to vote disproportionately for “liberal” outcomes, such as outcomes favoring employees, consumers, small businessmen, criminal defendants (other than white-collar defendants), labor unions, and environmental, tort, civil rights, and civil liberties plaintiffs. Judges and Justices appointed by Republican Presidents are predicted to vote disproportionately for the opposite outcomes.

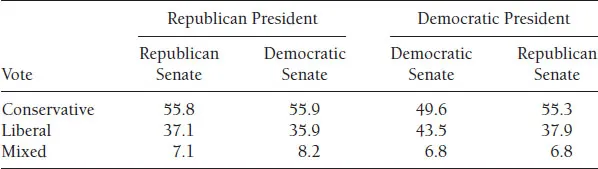

Other evidence of a judge’s political leanings is sometimes used in lieu of the party of the appointing President, such as preconfirmation editorials discussing the politics or ideology of a judicial nominee.4 A neglected possibility is a fourfold classification in which the intermediate categories would consist of judges appointed when the President and the Senate majority were of different parties (“divided government”). However, Nancy Scherer finds no difference in the decisions of federal district judges appointed by “divided” versus “united” government,5 and I find only a small difference (as shown in Table 16) in the case of federal court of appeals judges appointed by Republican Presidents. But when the President is a Democrat, it makes a significant difference whether the Senate is Democratic or Republican, probably because the Republican Party is more disciplined than the Democratic Party and therefore better able to organize opposition to a nominee.

Table 1 Judicial Votes in Courts of Appeals as Function of United versus Divided Presidency and Senate, 1925–2002 (in percent)

Sources: Appeals Court Attribute Data, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/auburndata.htm (visited July 17, 2007); U.S. Court of Appeals Database, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/appctdata.htm, www.wmich.edu/-nsf-coa/ (visited July 17, 2007). Votes were weighted to reflect the different caseloads in the different circuits. “Mixed” refers to multi-issue cases in which the judge voted the liberal side of one or more issues and the conservative side of the other issue or issues.

Table 2 Judicial Votes in Courts of Appeals as Function of United versus Divided Presidency and Senate, Judges Serving Currently (in percent)

Sources: Appeals Court Attribute Data, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/auburndata.htm (visited July 17, 2007); U.S. Court of Appeals Database, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/appctdata.htm, www.wmich.edu/-nsf-coa/ (visited July 17, 2007). Votes were weighted to reflect the different caseloads in the different circuits. “Mixed” refers to multi-issue cases in which the judge voted the liberal side of one or more issues and the conservative side of the other issue or issues.

Table 2 is similar to Table 1 except limited to currently servingjudges. Notice that the effects of divided government on judicial voting are more pronounced than in Table 1, consistent with the strong Republican push beginning with Reagan to tilt the ideological balance of the courts rightward. Notice also that federal judicial decisions as a whole tilt toward the conservative end of the spectrum and that the tilt is more pronounced among currently serving judges.

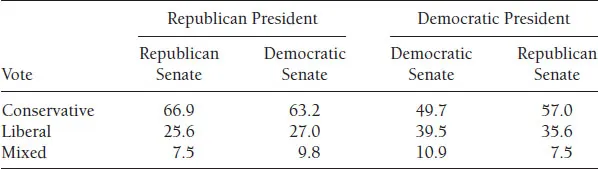

Table 3 Ideology of Currently Serving Justices and the Appointing President

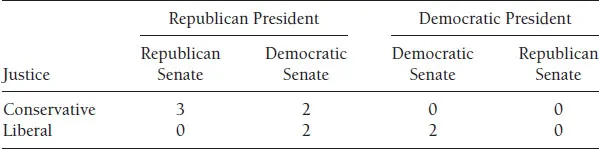

Table 4 Conservative and Liberal Supreme Court Justices as Function of United versus Divided Presidency and Senate, Justices Serving Currently

Presidents differ in their ideological intensity, and taking account of that difference can improve the accuracy of the attitudinal model. Seven of the nine current Supreme Court Justices were appointed by Republican Presidents, but it is more illuminating to note that four conservative Justices were appointed by conservative Republicans (Scalia and Kennedy by Reagan, and Roberts and Alito by the second Bush), two liberal Justices by a Democratic President (Ginsburg and Breyer, appointed by Clinton), and one liberal and two conservative Justices appointed by moderate Republicans (Stevens by Ford, Souter and Thomas by the first Bush). See Table 3.

There is also a divided-government effect in Supreme Court appointments, as shown in Table 4.

Whatever the method of determining a judge’s political inclinations, and whatever the level of the judiciary (Supreme Court, federal courts of appeals—on which there is now an extensive literature7—or federal district courts8), the assumed inclinations are invariably found to explain much of the variance in judges’ votes on politically charged issues. The hotter the issue (such as abortion, which nowadays is much hotter than, say, criminal sentencing), the greater the explanatory power of the political variable. The attitudinal theory is further supported by the unquestionable importance of politics in the appointment and confirmation of federal judges;9 by the intensity of congressional battles, almost always politically polarized, over the confirmation of federal judges and particularly Supreme Court Justices; and by the experiences of lawyers and judges. Every lawyer knows that the accident of which judges of a court of appeals are randomly drawn to constitute the panel that will hear his case may determine the outcome if the case is controversial. Every judge is aware of having liberal and conservative colleagues whose reactions to politically charged cases can be predicted with a fair degree of accuracy even if the judge who affixes these labels to his colleagues would not like to be labeled politically himself.

Further evidence is the tendency of both Supreme Court Justices and court of appeals judges to time their retirement in such a way as to maximize the likelihood that a successor will be appointed by a President of the same party as the one who appointed the retiring Justice.10 Still another bit of evidence is what might be called “ideology drift”—the tendency of judges to depart from the political stance (liberal or conservative) of the party of the President who appointed them the longer they serve.11 A judge closely aligned with the ideology of the party of the President who appointed him may fall out of that alignment as new, unforeseen issues arise. A judge who was conservative when the burning issues of the day were economic may turn out to be liberal when the burning issues become ones of national security or social policy such as abortion or homosexual rights.

There is more: the outcome of Supreme Court cases can be predicted more accurately by means of a handful of variables, none of which involves legal doctrine, than by a team of constitutional law experts.12 While there is a high correlation between how a given federal appellate judge (court of appeals judge as well as Supreme Court Justice) votes for the government in nonunanimous (hence “close”) constitutional criminal cases and in nonunanimous statutory criminal cases, there is a low correlation between the votes of different judges for and against the government in criminal cases.13 Some judges have a progovernment leaning, others a prodefendant leaning, and these leanings appear to be what drives their votes in close cases whether the case arises under the Constitution or under a statute—though from a legalist standpoint the text of the enactment being applied ought to drive the outcome, and there are huge textual differences between the Constitution and statutes. Apolitical judges would not be expected to vote the same way in both types of case.

All this is not to say that all judicial votes are best explained as politically motivated,14 let alone that people become judges in order to nudge policy closer to their political goals. We shall see in subsequent chapters that to explain the political cast of judicial decisions does not require assuming that judges have conscious political goals. No attitudinal study so finds, and data limitations cannot explain the shortfalls. Even at the level of the U.S. Supreme Court many cases do not involve significant political stakes, but that cannot be the entire explanation either. Think of Oliver Wendell Holmes. The publication of his correspondence after his death revealed that he was a rock-ribbed Republican, yet he voted repeatedly to uphold liberal social legislation (such as the maximum-hours law at issue in the Lochner case, in which he famously dissented) that he considered socialist nonsense. He may of course have been an exception among Supreme Court Justices in this as in so many other respects. He may have few successors in point of political detachment in today’s more politicized legal culture.

We get a sense of the attitudinal model’s predictive limitations in Tables 5 and 6, in which judicial votes that lack any political valence are coded as “other,” and the liberal, conservative, mixed, and other votes are correlated with the party of the President who appointed the judge who cast the vote. Notice that apart from the substantial percentage of votes that were either mixed or other, a large percentage of conservative votes were cast by putatively liberal judges (judges appointed by Democratic Presidents) and a large percentage of liberal votes were cast by putatively conservative judges. Notice, as in the earlier tables, the apparent trend toward the increased politicization of court of appeals voting resulting from judicial appointments by Republican Presidents. But notice, too, that the differences between the two types of judge, exhibited in the first two rows of the tables, though significant, are only partial. And a comparison just of means obscures the fact that the distributions overlap; some judges appointed by Republican Presidents are less conservative than some appointed by Democratic Presidents. This does not refute the attitudinal model, but it does highlight the fact that the party of the appointing President is an imperfect proxy for a judge’s judicial ideology. One reason is that ideological issues important to judges need not have salience in political campaigns; capital punishment is a current example. Another reason is that judges pride themselves on being politically independent rather than party animals.

Table 5 Judicial Votes in Courts of Appeals as Function of Party of Appointing President, 1925–2002 (in percent)

Vote | Republican President | Democratic President |

Conservative | 42.2 | 37.6 |

Liberal | 28.1 | 33.3 |

Mixed | 5.9 | 5.1 |

Other | 23.9 | 23.9 |

Sources: Appeals Court Attribute Data, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/auburndata.htm (visited July 17, 2007); U.S. Court of Appeals Database, www.as.uky.edu/polisci/ulmerproject/appctdata.htm, www.wmich.edu/-nsf-coa/ (visited July 17, 2007). Votes were weighted to reflect the different caseloads in the different circuits. “Mixed” refers to multi-issue cases in which the judge voted the liberal side of one or more issues and the conservative side of the other issue or issues.

Table 6 Judicial Votes in Courts of Appeals as Function of Party of Appointing President, Judges Serving Currently (in percent)

...