![]()

chapter 1

The Breakup: The Soviet Oil Industry Disintegrates

Today the veteran “oil generals” who ran the Soviet oil industry look back on their past as though it all happened on a remote planet. Valerii Graifer, now chairman of the board of LUKoil, Russia’s largest private oil company, is today a white-haired gentleman in his eighties. His modest and courtly manner gives little hint of the power he once wielded. In the second half of the 1980s, the last years of the Soviet Union, Graifer, as head of the oil ministry’s main administration in West Siberia, controlled over 400 million tons per year (8 million barrels per day) of crude oil production, then over 13 percent of the world’s total. He held the imposing rank of USSR deputy minister of oil, and technically, that made him the boss of the entire West Siberian oil administration, then known by the jaw-breaking acronym of Glavtiumenneftegaz, or “Glavk” for short.

But in reality Graifer was not the most powerful figure on the scene. There was one man mightier than he, one whose support Graifer badly needed, the head of the Communist Party apparatus in West Siberia’s oil capital of Tiumen, Gennadii Bogomiakov. Valerii Graifer recalls:

I was an unusual combination for the Soviet oil industry—not an engineer but an economist, and even more unusual, a Jew. I had headed the oil industry in Tatarstan and I had a reputation as a manager and trouble-shooter. In the mid-1980s, when the West Siberian oil industry ran into trouble, I was sent to Tiumen.

I knew Tiumen well. My grandparents had been exiled there from Saint Petersburg after the revolution of 1905. I had spent summers in Tiumen as a boy. But when I returned as head of Glavtiumenneftegaz I ran into a brick wall. Bogomiakov would not even meet with me. Finally one evening I was invited to a party at his home. I was seated at the bottom end of the table, and everyone ignored me. But as the evening went on Bogomiakov and his friends began singing Siberian folksongs. To my own surprise—and theirs—I found myself joining in. Those were the songs from my boyhood, buried away in the back of my memory, and I knew them all. We sang all through the night. By morning Bogomiakov and I were fast friends, and I never had any trouble with him after that.1

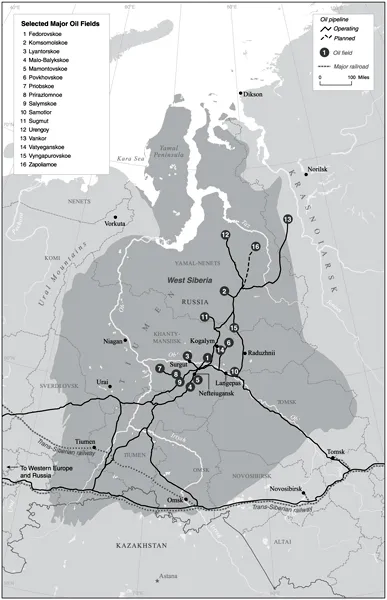

MAP 2 West Siberian basin: Major oilfields and transportation routes.

West Siberia by the late 1980s was the powerhouse of the Soviet oil industry, producing two-thirds of all Soviet oil. It was the industry’s third generation: from its birthplace in Baku in the early 1900s, it had migrated to the Volga-Urals in the 1940s and 1950s, before reaching its peak as the world’s leading producer in the 1970s and 1980s, thanks to the giant oilfields of West Siberia’s Tiumen Province. It was in Tiumen, in the Arctic swamps of the middle Ob’ River basin, that the final drama of the rise and fall of Soviet oil was played out.

The Stovepipe System

It was a simpler world, in retrospect. There was a vertical chain of command, running from the headquarters of the USSR Ministry of Oil in Moscow, located in a grand prerevolutionary palace facing the Kremlin directly across the Moscow River, down through a hierarchy of divisions and subdivisions to the working level in West Siberia, the “production associations” (in Russian, proizvodstvennye ob”edineniia) that controlled the operating units in the field, the so-called NGDUs, later familiar to Western oilmen from Tulsa to Calgary as “engadoos.”2

But the Ministry of Oil’s domain was limited to the production and transportation of crude oil and condensate—in oilspeak, the “upstream.” As the crude oil flowed into the pipeline system, the producers turned over title to the pipeline operators, at that time the transportation department of the Ministry of Oil. Title then passed to the next link in the chain, the refineries belonging to the Ministry of Oil Refining and Petrochemicals, which handled all of the “midstream.” Refined products moving inside the domestic economy were controlled by yet another monopoly, Transnefteprodukt.3 A specialized agency of the Ministry of Foreign Trade, Soiuznefteeksport, had a monopoly over oil exports.

Hard-currency proceeds from crude oil sales—the most valuable and politically sensitive part of the oil flow—were kept in special accounts of the USSR Bank for Foreign Trade (Vneshtorgbank).4 The key point about this system is that the upstream oil producers, the ones who actually produced the largest single part of the export wealth,5 saw very little of this hard-currency flow, and none of it directly. The oil ministry bargained, like the others, for its annual share of hard currency, which it then doled out to the upstream producers and the pipeline operators for special projects requiring foreign purchases approved by the planners.

Within these segregated state structures, an upstream crude producer could (and generally did) spend an entire career without ever talking to a refiner, a distributor, or an export trader, except at the very top of the system.6 Upstream producers had little exposure to the outside world. If they needed equipment from abroad, the Ministry of Foreign Trade bought it for them. For the oil generals, big men though they were in their own home provinces, a trip abroad (where they were herded about in closely watched delegations and given only miserly expense allowances) was just as much of a prized adventure as it was for most other Soviet citizens.

All oil in those days was the property of the state and was managed by the central planning system. The different players in the Soviet system took their cues not from market signals but from the central planners in Moscow, who set production targets and allocated supplies and manpower. Even in the oilfields the Ministry of Oil had little control beyond its own wells and pipelines. All the support systems it needed—power lines and electricity supply, housing and road construction, pipe and drill bits, helicopter transport, and most other key services—were the province of other ministries.7

Something was needed to bind these parts together, and for that purpose the Soviets had put in place a separate command structure, the core of which was the regional apparatus of the Communist Party. The true boss of any Soviet region, the all-powerful viceroy of the ruling Politburo, was the first secretary of the party’s province committee (known as the obkom). His job was to offset the rigidities, the missed cues, the conflicting plans, and the petty jealousies of the local offices of the various ministries, by cajoling, negotiating, knocking heads, and if necessary appealing to Moscow for authority over the closed telephone line, the vertushka, that ran straight via a hardwired connection to the Politburo.8 To bind together the vertical stovepipes of the Soviet command economy, the party apparatus provided the all-important local welding.9

Gennadii Bogomiakov, whom we have already met at his dinner table, ruled as the party obkom first secretary in Tiumen Province from 1973 to his overthrow in January 1990. He was one of the true veterans of the industry, a geologist by training, formerly head of West Siberia’s leading institute for oil geology and exploration. He had worked in Tiumen from the earliest days of the West Siberian oil boom in the 1960s. Bogomiakov had the supremely delicate job of walking the tightrope between Moscow’s constant demands for more oil and the local oilmen’s equally constant lobbying for lower targets. In those days, the West Siberian oil industry was split between the so-called optimists (who pushed for maximum output growth, under relentless political pressure from the Kremlin) and pessimists (known as predel’shchiki), who warned that to push the fields too hard was to invite disaster. Being labeled a predel’shchik was likely to cost you your job. Only the celebrated discoverer of Samotlor, Viktor Muravlenko, had the prestige and courage to stand up to the Kremlin and its constant demands for more oil. Muravlenko had a direct line to Prime Minister Aleksey Kosygin and could take his protests straight to the top. But the direct line worked both ways. Muravlenko once told Valerii Graifer that Kosygin called him one day and pleaded, “We’re short of bread [s khlebushkom plokho]—give us 3 million tons of oil above the plan.”10

Bogomiakov had the unenviable task of holding the middle between the Kremlin and the oilmen. “He was a serious and intelligent man,” recalls Graifer, “and he managed to protect us against the optimists.” Others are less forgiving. According to a local historian, Bogomiakov’s constant hounding, coupled with that of the ministry in Moscow, broke Muravlenko’s health and drove him to an early grave. In 1977 Muravlenko dropped dead of a heart attack in the lobby of the Rossiia Hotel in Moscow, following a particularly stormy exchange with the oil minister, Nikolai Mal’tsev. Following his death, the pressure on the predel’shchiki turned into a witch hunt. Muravlenko’s successor at Glavtiumenneftegaz, Feliks Arzhanov, was fired in 1980 for trying to hold the 1985 output target at 340 million tons (6.8 million barrels per day) (West Siberia in 1980 had produced 312.7 million) [6.3 million barrels per day], while Bogomiakov demanded an increase to 365 million tons (7.3 million barrels per day).11 In the early 1980s hundreds of senior managers, including two more heads of the Glavk, were purged from the West Siberian oil industry for failing to meet the higher targets.12 Whatever Bogomiakov’s exact role in these battles, all agree that he was a consummate artist on the tightrope. He survived three political successions and two major shakeouts in the Siberian oil industry all through the 1970s and 1980s, before the death throes of the whole Soviet system finally brought him down.13

Markets and economics had no place in this system. The Soviet command economy was not really an economy at all; it was a bureaucratic pump for moving resources according to the priorities set by the political leadership. It was largely indifferent to the fine weighing of value and cost against time and risk that is the essence of free-market economic thinking and business strategy. The skills that the system valued most were those of scientists and engineers—geologists, petroleum engineers, and drillers—who then morphed into political managers as they rose up through the ranks. Whereas a senior executive in a modern international oil company, in addition to technical expertise, is also a specialist in financial strategy and cost management, aiming at optimizing return on capital, Soviet oilmen were engineers who lived in a noneconomic world of administratively set production targets. An international oil company today contracts out much of the actual job of finding and producing oil to service companies. In contrast, an upstream Soviet oil enterprise for all practical purposes was a service company, responsible for every aspect of development and production and directly employing tens of thousands of workers.14

Ignoring cost led Soviet leaders and planners to misallocate resources on a grand scale. Throughout the Soviet period, but particularly from the 1960s on, they poured capital and manpower east of the Ural Mountains into the Siberian hinterland, building massive permanent cities in some of the coldest and least hospitable places on earth. In West Siberia, they built large permanent settlements in the middle of Arctic swamp and tundra, one-company towns that later proved hostages to misfortune.15

The practical consequence of all this is that the true costs of developing and producing Soviet oil, being largely invisible, were systematically discounted. So long as world oil prices were high and the fields were young—and both conditions prevailed between 1973 and 1980—this could be ignored. But in the first half of the 1980s, world oil prices fell sharply and remained at low levels in the second half of the decade,16 while at the same time the annual growth in Soviet oil production abruptly slowed, forcing the Soviet government to increase oil investment sharply in order to offset some of the loss in revenues. This reflected, among other things, the fact that the Soviet oil industry was running up against an inexorable fact of nature: the rate of discovery of large new oil fields was slowing down. This had nothing to do with Soviet planning; it simply reflected the log-normal distribution of field sizes characteristic of oil provinces around the world. By the 1980s, the Soviet oilmen were developing ever-smaller and more costly fields.17

Thus, from 1980 on, as exploration and production costs increased and oil and gas export revenues declined, the rents from oil plummeted. If it is not quite true, as some studies have concluded, that more money was going down into the wells than was coming up, the drop in oil and gas rents was dramatic enough, from a peak of about $270 billion per year in 1980–1981 to less than $100 billion in 1986 and after.18 Most of this decline was due to falling world oil prices, but rising production costs were also to blame; between 1983 and 1987, the delivered costs of Soviet oil grew by two-thirds.19

The Soviet command economy had always depended on the rents from natural resources—although not so much for export as for internal use.20 But by the 1980s the Soviet political leadership had grown to rely not only on oil for domestic consumption but also on oil-export revenues, while the oil industry was equally dependent on a high rate of growth of investment. A crisis in the oil industry was bound to translate into a crisis for the entire command economy—and vice versa.21

A World of Survivors

The West Siberian oilfields in the 1970s and 1980s were a tough but colorful and boisterous world, a multiethnic melting pot in which, in the early years at least, everyone came from someplace else. Roughnecks and roustabouts, the foot soldiers of any oil industry, were recruited from the older oil provinces, from Ukraine and the Volga Basin and the Caspian Sea, and sent to work in makeshift settlements under incredibly harsh conditions. (Prison labor, however, played no role in the West Siberian oil and gas industries, since they developed even as the Gulag empire was being shut down.22) The higher ranks, composed of geologists, engineers, and managers, were an equally varied lot. Farman Salmanov, the most legendary name among the pioneer geologists of the region, recalled that i...