![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Gentlemen Banking Before 1914

WHEN PIERPONT MORGAN was born in 1837, the United States was barely sixty years old, a union of states uneasily bound together across ideological, economic, and geographic divisions. Morgan was in his late fifties when he reorganized his father and mentors’ firms into what became the House of Morgan. By that time, the United States had become a nation by fire, an industrializing country with communications, transportation, and technological advances far beyond what had been available before the Mexican-American and Civil Wars. The Morgans’ position within the financial community was dependent upon this growth in American national infrastructure. Their rise to the apex of American finance was aided by certain historical and structural factors that encouraged economic consolidation, such as the relative position of the United States to Europe and the limited government regulation of private banking.

The firm’s ties that developed under these conditions, including the relationships and traditions of gentlemen bankers, became the focus of progressive critics and government investigators at the Pujo Hearings. If the Morgans’ relationships have traditionally been perceived as a collusive and homogeneous network, this perception of gentlemen banking relationships and power, including its private nature, hid the extent to which their interests were enabled by fundamental inequalities. These encompassed the divisions that deeply troubled American republican society in the post-Civil War, including those considered to be far removed from the concerns of elite businessmen and capitalists.

GENTLEMEN BANKERS BEFORE 1914

Pierpont Morgan was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1837. His mother, Juliet, was the daughter of a Unitarian minister and a descendant of James Pierpont, one of the founders of Yale University. Morgan’s father, Junius, was the grandson of a Unitarian minister and a descendant of Joseph Morgan, one of the founders of the Aetna Insurance Company. By the early 1840s, the Morgan family had already accumulated a substantial fortune. Pierpont was the first of Juliet and Junius’s five children and the only surviving son. The year before Junius joined George Peabody as his partner in London, Pierpont graduated from public school in Boston. He was sent to Germany to study at the University of Gottingen after which he began his apprenticeship in New York in 1857.1

After George Peabody retired, Junius founded the firm of J. S. Morgan & Co. (JSM & Co.) in London (1864). In 1871, Junius merged the Morgan interests with those of Anthony Drexel (1826–1893), a Philadelphia merchant banker, whose father, Francis, was the founder of the Drexel bank. Together, they formed Drexel, Morgan & Co. (DM & Co.) with Pierpont as its head. DM & Co. served as JSM & Co.’s American arm. While Drexel himself had two sons, they were unwilling or unable to take up his position. After Junius died in 1890 and Drexel died in 1893, Pierpont Morgan founded J. P. Morgan & Co. based in New York, which became the leading branch of a newly organized house.

In total, there were four firms in the House of Morgan. The Philadelphia firm was renamed Drexel & Co. (D & Co.).2 JSM & Co. remained the British branch of the House of Morgan until 1909 when it was renamed Morgan, Grenfell & Co. (MG & Co.).3 The Paris branch, which had been founded in 1868 under the Drexel interests, was called Morgan, Harjes & Co. (MH & Co.). It was renamed Morgan et Cie. after the death of Herman Harjes (1875–1926), who was the son of its founder, John Harjes.4 Only J. P. Morgan & Co. and Drexel & Co. partners were bound by the same partnership agreement. The American branches were partners as firms in the European houses. The Paris and London branches had their own agreements though some partners overlapped.5 Under Pierpont’s leadership, the banks worked together and were identified as one collective—an international house whose expertise was in the American market.

As merchant or gentlemen bankers, the Morgans’ roots lay in the business of international trade. The fact that the Morgans had multiple branches on both sides of the Atlantic was critical to their success because the different houses provided each other with access to information on the ground at a time when reliable information was expensive and rare.6 Merchant or gentlemen banking traditionally had a high barrier to entry because it was extremely personal, a structure designed to limit risk in a historical context that offered little formal protections or structures to enforce contracts across national boundaries and vast distances.7 Using the bank’s “name and credit” through instruments such as the “bills of exchange” and “commercial letter of credit,” merchant bankers like the Morgans were able to provide a multitude of financial services from supplying credits for international trade to foreign exchange to loans to governments to underwriting, while also navigating multiple currencies, laws, customs, and languages.8 The Morgans’ relations in international trade were a central part of the family bank’s business in investment banking.

The fortune of the House of Morgan was also closely tied to American industrial and national development. At a time when the United States was a debtor nation in need of capital, they became an important intermediary between European investors and America’s first big business, the railroads. From their connections in merchant banking and international trade, they built a financial network for railroads and industries in the United States. If their prominence in the United States stemmed largely from their position as a bridge between the United States and Europe, the significance of their position was heightened by the differences between the two spaces that were being bridged, particularly before the First World War.

Unlike England, which had a central bank since the seventeenth century, the United States (though much younger in years) did not develop a central bank until 1913.9 This was only one of the considerable structural advantages the European markets had over the American market, which tended to favor private international bankers.10 In the decentralized environment of the “new world,” private banks had considerable influence in the field of foreign finance because of the ways in which the legal structure gave them advantages over their competitors. After the passage of the National Banking Act in 1863, nationally chartered commercial banks faced more state regulation than private banks and were prevented from opening branches abroad. Blocked from moving into international finance on their own, they formed working relationships with private banks, in some cases through interlocking directorships, ties between firms formed by the common membership of an individual director.11

These ties allowed commercial banks like National City Bank (f. 1812) and First National Bank of New York (f. 1863), which were founded as banks to further government and national development, to take advantage of the experience and connections of private banks like J. P. Morgan & Co., which then took advantage of the deposits and reach of its collaborators.12 The relationships were solidified through formal economic ties and, as we shall see, personal ties between partners and directors.13 As long as competition and access to capital were limited, and until corporations had the ability to raise substantial funds through surplus profits, private banks had the potential for enormous influence, relative to even their considerable reputations and connections. Through a legal and economic structure that allowed them to access reserves of other banks, commercial banks, who were made in effect national depositories, became the collaborators of elite private banks, not their competitors.14

Whether or not Pierpont Morgan was conscious of the structural and historical factors that worked in his favor, he disliked competition, believing it to be wasteful and inefficient. That much was evident in the Morgans’ active embrace of a cooperative structure known as the syndicate. While the history of syndicates dates back centuries, syndicates were first utilized in the United States in the early nineteenth century. The first underwriting syndicate appeared after the Civil War. Syndicates became more frequent by the late nineteenth century as circumstances changed such that one party could not assume all the risk and provide all the capital necessary in the economic expansion of the United States starting with the railroads, the pioneers of American big business.15

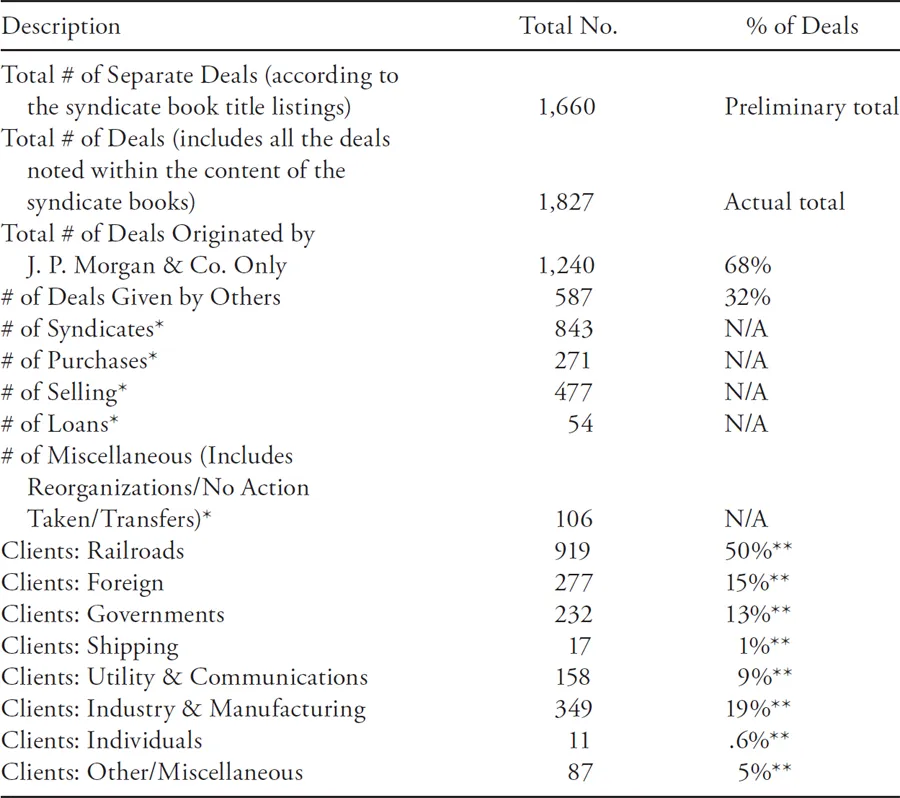

The general process of creating a syndicate began when a client, such as a railroad, needed to raise a large amount of capital (usually several million dollars) for improvements, acquisitions, or refunding of debt and approached the Morgans to underwrite a bond offering. (Between 1894 and 1934, approximately 50 percent of all Morgan undertakings involved railroads. Other clients included industrials [19 percent], state or national governments [13 percent], or utilities [9 percent].) (See Table 1.) The Morgans would then approach other banks with an offer to share in the underwriting. Very close associates and friends, such as First National and National City, might be allotted participations on the same terms as the Morgans. They were called the managing group.

Table 1 J. P. Morgan & Co.’s Syndicate Books Summary Characteristics, 1894–1934

* Note that one deal listed in a syndicate book could have many different stages that included syndicates, purchases, and sales.

** % of actual total. Note that this refers to the percentage of deals that had a client of that type. For example, a client could be coded both as “foreign” and as “government.”

Source: J. P. Morgan & Co. Syndicate Books, ARC 108–ARC 119, Pierpont Morgan Library (PML)

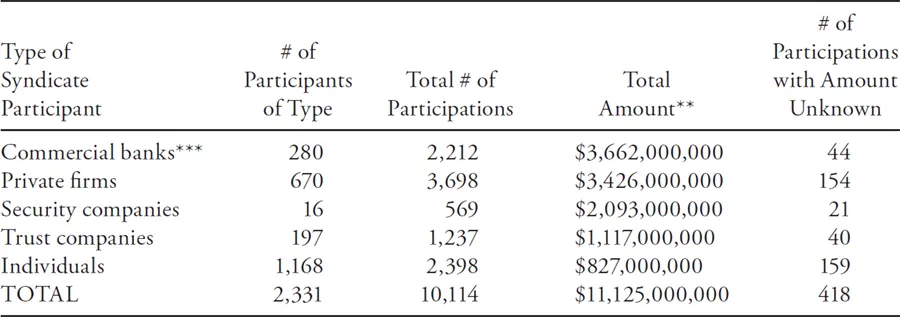

Other banks would be invited to participate as members of the purchasing group with the amount of the participation set by the Morgans usually on terms slightly less advantageous than the managing group. The final group was called the distributing group and like the other groups could be made up of individuals, banks, trust companies, or other types of syndicate participants. The distributing group was usually the largest group and the least prestigious. Their responsibility was to sell the offering to the public and other institutions. The Morgans were usually allotted a fee for their services, usually either one-half of 1 percent or 1 percent of the entire amount, but they also made profit on the difference between the terms of the managing, purchasing, and distribution groups. At each stage, the Morgans kept a certain portion of the syndicate for themselves, but the majority of the underwriting was done by the participants with few exceptions. (See Table 2.)

Participation in a syndicate had many benefits; the most obvious one was to profit at less risk than one might have on one’s own; the less obvious but more important benefit was to expand and strengthen one’s network.16 Syndicates were also informal in that they did not involve contracts and were meant to avoid lengthy and expensive legal conflicts. In other words, they were monitored by a community and not by a state legal structure, which did not either exist or did not function efficiently to enforce contracts between parties. Syndicates could also be used as a way to control the competition by including those who could seriously challenge or disadvantage or attack the price of the issue.17 Syndicates thus encouraged the formation of a cooperative community across competing economic groups. They were indicative of the general trend toward economic consolidation and cooperation at the turn of the century.18

Table 2 J. P. Morgan & Co.’s Syndicates Participants by Type, 1894–1934*

*Does not include insurance companies, savings banks, and others (e.g., trusts and estates, universities, and churches)

**Rounded to the nearest million

***Does not include foreign banks (of which there were 39)

Source: J. P. Morgan & Co. Syndicate Books, ARC 108–ARC 119, Pierpont Morgan Library (PML)

The House of Morgan’s American syndicate data, which included substantial international issues, show the extent to which the Morgan bank did not work alone. Between 1894 and 1914, J. P. Morgan & Co. managed 352 syndicates for a total of approximately $4.3 billion. This was unlike actions related to purchases, for example, which J. P. Morgan & Co. usually acted on its own or for a client.19 The syndicate books show 1,530 different syndicate partici...