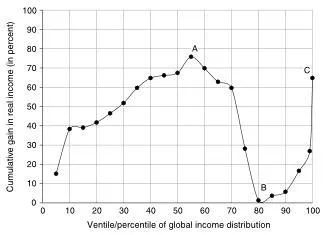

The gains from globalization are not evenly distributed.

EXCURSUS 1.1. Where Do the Data for Global Income Distributions Come From?

There is no global household survey of individual incomes in the world. The only way to create a global income distribution is to combine as many national household surveys as possible. Such household surveys select a random sample of households and ask a number of questions on demographics (age, gender, and other characteristics of respondents) and location (where the household lives, including what province, whether in a rural or urban area, and so on), and, for our purposes the most important, questions about the sources and amounts of household income and consumption. Income data include wages, self-employment income, income from ownership of assets (interest, dividends, rental of property), income from production for the household’s own consumption (very common in poorer and less monetized economies where households produce their own food), social transfers (government-provided pensions, unemployment benefits), and income deductions such as direct taxes. Consumption data cover money spent on everything from food and housing to entertainment and restaurant services.

Household surveys are the only source of such individualized, detailed information on incomes and expenditures that cover the entire distribution, from the very poor to the very rich. By contrast, data from fiscal sources, such as tax records, generally include only the households of better-off people, that is, those paying income taxes. There are many such households in the United States, but very few in India. Thus, fiscal data cannot be used to generate a worldwide distribution of income.

The size of household surveys varies. Some are large because the country is large: the Indian National Sample Survey includes more than 100,000 households, or more than half a million individuals; the US Current Population Survey includes more than 200,000 individuals. Many surveys are small, with about 10,000–15,000 people. Such survey data, while never easily available, have recently become more accessible to researchers. For example, in the 1970s and 1980s, not only did relatively few countries conduct surveys, but it was very rare that researchers could get access to “microdata” (that is, individual household data, anonymized to preserve confidentiality). Income distributions were estimated using the government-published fractiles of income recipients (e.g., so many households with incomes between $x and $y). More recently, with greater openness of statistical offices and improvements in the processing of large data sets, almost all data, with the notable exception of China, are available at the micro level. This presents significant advantages to researchers: they can redefine income or consumption so as to be comparable across countries or produce inequality measures that are based on households, individuals, or what are called “equivalent units” (adjusting for the fact that larger households enjoy some economies of scale; that is, they do not need a proportional increase in income to be as well-off as smaller households). None of these adjustments is possible without access to the microdata.

The main sources of such microdata are the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), which includes harmonized survey data (i.e., definitions of income variables that are made as comparable as possible between the countries), mostly from rich countries; the World Bank, which has extensive country coverage and makes some surveys available to outside researchers while other data are available only to World Bank staff; the Social and Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC), located at Universidad de la Plata in Buenos Aires; and the Economic and Research Forum (ERF), located in Cairo, which includes surveys from the Middle East. All of these sources can be easily found on the Internet, but often access to the microdata is restricted to noncommercial uses and “bona fide” researchers, or access is difficult because of the need to know how to download massive databases and apply statistical programs. In addition, for a number of countries (e.g., India, Indonesia, and Thailand), although the data can be accessed directly from statistical offices, that process requires clearance and long waiting periods. So while access to data is becoming much better, it is still not easy. It is also important to realize that even if all the data were suddenly to become easily accessible, factors such as the sheer size of the files, complicated definitions of the variables, and comparability issues mean that income distribution data would never be as simple to use as much more aggregated statistics like Gross National Product.

Now, if each country were to conduct such surveys annually, we could, by collating them, obtain annual estimates of global income distribution. Only rich and middle-income countries have regular annual surveys, however, and even among these countries, annual surveys are something of a novelty. And in many poor countries, especially in Africa, household surveys are done at irregular intervals, on average every three or four years. There are also numerous countries that do surveys only at very long intervals, either because they have no money or technical expertise to field them or because they are at war, civil or foreign. This is the reason why global data can be put together only at approximately five-year intervals (as in this chapter) and are centered around one year, called the “benchmark year,” which includes surveys from that year and one or two surrounding years.

National household surveys represent the first building block for determining the global income distribution. The second building block is conversion of such income or consumption data from local currencies into a global currency that should in principle have the same purchasing power everywhere. Why is this important? Because to assess people’s incomes and make them comparable, we have to allow for the fact that price levels differ between countries. Thus, to express the real standard of living of people who live in very different environments (countries), not only do we need to convert their incomes into a single currency, but we also have to account for the fact that poorer countries generally have lower price levels. Put in simpler terms, it is less costly to attain a given standard of living in a poorer than in a richer country: ten dollars will buy more food in India than in Norway. This second building block relies on an exercise called the International Comparison Project (ICP) that is conducted at irregular intervals (the last three rounds were done in 1993, 2005, and 2011) and whose objective is to collect price data in all countries of the world and to use these data to calculate countries’ price levels.

The ICP is the single most massive empirical exercise ever conducted in economics. Its final products are the so-called PPP (purchasing power parity) exchange rates. The PPP exchange rate is the exchange rate between, say, the US dollar and the Indian rupee, such that at that exchange rate a person could buy the same amount of goods and services in India as in the United States. To give an example, consider the results for 2011. The market exchange rate was 46 Indian rupees for 1 US dollar. But the estimated PPP exchange rate was 15 rupees per dollar. In other words, if you lived in India, you needed only 15 rupees to buy the same amount of goods and services as a person living in the United States could have bought with 1 dollar. The reason why you needed only 15 rupees (and not 46) is because the price level in India was lower; we can say that it was about one-third (15/46) of the US price level.

It is by applying these PPP exchange rates to the incomes from national household surveys that incomes are converted into PPP (or international) dollars and made comparable across countries. This conversion then enables us to calculate global income distribution. We can see, then, that global income distribution is impossible to calculate without two enormous empirical exercises: hundreds of national household surveys, and individual price data that are aggregated into national price indexes.

However, such massive exercises have their own problems. For household surveys, the most important problem is the imperfect inclusion of people at both ends of the income distribution: the very poor and the very rich. The very poor are omitted because household surveys choose households randomly based on place of residence. Homeless people and institutionalized populations (soldiers, prisoners, and students or workers who live in dormitories) are thus not included, and these people are generally poor. At the other end of the spectrum, the rich tend to underreport their incomes (especially their income from property) and, more alarmingly for researchers analyzing income data, sometimes refuse to participate in surveys altogether. The effect of such refusals on income distribution is difficult to prove directly (because one obviously does not know the income of a household that has refused to be interviewed) but can be estimated from where those who refuse to participate live. It has been estimated that US income inequality might be underestimated by as much as 10 percent because of such nonparticipation (Mistiaen and Ravallion 2006).

These problems are similar or even more serious in other countries and are reflected in two discrepancies between household surveys and macrodata: first, income and consumption reported from household surveys do not fully match household private income and consumption calculated from national accounts (that is, from GDP calculations), and second, statistical discrepancies (called errors and omissions) occur in balance of payments data because of, among other things, money transferred to tax havens (see Zucman 2013, 2015), which, for obvious reasons, is unlikely to be reported in surveys. It is therefore safe to say that household surveys underestimate the number of people who are poor (whatever the definition of poverty) and the number of people who are rich, and their incomes. Lakner and Milanovic (2013) try to adjust globally for the latter, but any such adjustment, while useful, contains a very large degree of arbitrar...