![]()

1 A Harsh and Spiritual Unity

There’s a magical feeling about being a United States Marine. I can’t describe it to you or to anyone. But other Marines, they understand.

—Major Rick Spooner, U.S. Marine Corps (retired)

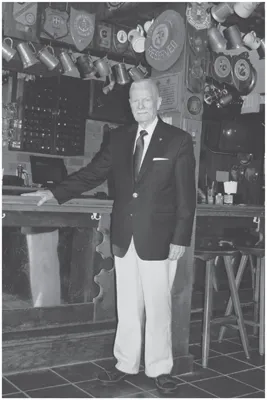

Rick Spooner is eighty-six years old and still gets a regulation “high and tight” haircut every week. In public he wears what Marines call “appropriate civilian attire”: a collared shirt neatly tucked into trousers, belt buckle in perfect alignment with his trousers’ centerline. Neither age nor the three wars he participated in show any effect on his body: it is trim, athletic, and ramrod straight. His mustache, white and pencil thin, is also regulation, neither touching the lips nor extending beyond the corners of the mouth. He calls civilians “sir” or “ma’am” unless he knows them well. But fellow members of the Corps are almost never addressed by rank. “When they walk in the door, it’s always ‘Hello, Marine,’ ” he explains. “Because that’s more important than being a general or a private or a lieutenant. They’re Marines. That’s what’s important.” His smile is engaging and genuine, his speech quick and articulate. When he talks about friends lost in World War II, even the youngest ones, his voice does not modulate much; he has long since made his peace with the dead. But when he speaks of the Corps itself—of its history, traditions, and unique spirit—his face reanimates and his voice gets quiet and impassioned. “The Marine Corps is not a job,” he insists, “it’s a vocation.”1

Rick owns and operates the Globe and Laurel Restaurant, which sits just outside the main gate of Marine Corps Base Quantico in northern Virginia. The Globe and Laurel is part restaurant, part museum, and part Marine Corps shrine. Almost every inch of wall space is covered with exhibits: captured weapons from two centuries of wars, medals, flags, and Rick’s own Japanese souvenirs from the Pacific. Every night, Marines come from the base and the surrounding areas to eat and to admire the living tribute to their organization. Rick visits with everyone: listening to the Marines, chatting with their friends, and, when asked, telling something of his nearly thirty years in the Corps and his service during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.

Like most of the Marines who fought in World War II, Rick was not drafted. He volunteered. When the war broke out, he never had any doubt which service he would join. He fell in love with the Corps the first time he ever saw a Marine. Working as a shoeshine boy on the docks of San Francisco, he would often see servicemen coming off the battleships in San Francisco Bay. The Marines always stood out: “Always in blues, marching down the street, looking tall and squared away, and never letting me shine their shoes, always referring me to the sailors.… The Marines were too proud to let a kid shine their shoes. And I thought, ‘Wow, they’re special, they’re different, they’re wonderful!’ ”

At fourteen, Rick dropped out of school and tried to enlist in the Corps by doctoring a birth certificate. He was caught and discharged after three days. By seventeen, he was in the Corps legally; by eighteen, he was an infantry rifleman fighting in the South Pacific. Before he was twenty-one, he had been wounded four times and seen many of his fellow Marines killed on the islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Okinawa. He was discharged when the war ended but missed the Corps too much to stay out. Three months later, he reenlisted at the same rank he had held for most of World War II: private first class.

Rick’s career in the Corps was unusual—he stayed twenty-nine years and rose to the rank of major—but his experience in World War II was not. Nor is his continued attachment to the Corps as a retiree atypical. There’s no such thing as an ex-Marine, veterans are fond of saying, only former Marines. People leave the Marine Corps, but it does not leave them. While Rick’s restaurant and the two autobiographical novels he wrote are uncommonly public displays of devotion, few veterans would disagree with his assertion that “there’s a magical feeling about being a United States Marine.”2

Rick Spooner at the bar of his restaurant, the Globe and Laurel, in Quantico, Virginia, 2011. (Photo by author)

THE “MAGIC” OF MARINE CORPS CULTURE

World War II did not create the Marine Corps feeling. As long as there have been Marines, they have insisted that they are superior to the other services and have located that superiority in transcendent nouns such as “esprit,” “spirit,” “mystique,” and “feeling.” But even though these stories and feelings existed before Pearl Harbor, the combat in the Pacific had a pronounced effect on them. There was a deep compatibility between the stories Marines brought to the war and the experiences they found once in it. Perceptions of mistreatment strengthened their claims of uniqueness and elitism, even though they and the Army performed, at times, almost identical missions.3 Their culture grew stronger because the fighting confirmed their best ideas about themselves and their worst fears about the other services, particularly the Army.

The most important stories Marines carried into war with them were a set of claims asserting unconditionally that Marines were, and always have been, unique and superior to all other military services. On the surface, these narratives of Marine exceptionalism were simple and almost tautological: Marines are special, better than any other armed service, its members claimed, and it is the feelings, traditions, and spirit of the Marines that make them so. Underneath this circular logic, however, lay an unspoken contract between the Marine and the Corps, one that traded comfort for prestige and lionized suffering and self-sacrifice as quintessential acts of devotion. This contract of suffering only grew stronger as the costs of war mounted in the Pacific. The result was a lasting bond, formed by shared stories and a broad network of kinship that encompassed both the living and the dead. And while some Marines probably considered the Corps nothing more than a job, for the majority it was much more: a vocation, an identity, and even a new family.

At its most basic level, Marine Corps culture functioned through a process of symbolic exchange.4 Being a Marine meant elitism, an intimate community, and access to a set of stories granted only to a few. But those benefits were not free. The costs of belonging to the Corps were more than the typical restrictions on freedom and autonomy found in any military culture. More so than in the other services, membership in the Marine Corps required an ideological commitment, the abandonment of previous civilian identities, and the adoption of a new set of stories and priorities. One officer put it well a decade after World War II: “The Marine Corps must seek to possess the souls of its personnel as earnestly as it strives to condition their bodies.”5 As Rick Spooner and so many other veterans attest, once adopted, the Corps’ stories and priorities often lasted a lifetime.

Violence was an essential component of the Marines’ cultural contract. What made Marines different, new recruits quickly learned, was an impressive capacity to endure discomfort. That capacity was tested and proved in boot camp, where the suffering was usually limited to verbal abuse, exhausting exercises, and perhaps the occasional beating. But once in combat, the process of exchanging suffering for prestige came at a higher cost. As the price of Marine prestige grew, so too did its members’ valuation of that title. The Corps’ steadily increasing casualties in World War II—which were twelve times greater in the last year of fighting than they were in the first—further convinced Marines that their service was superior to the others around them.6

At first glance, this claim that increasing suffering created greater attachment and dedication to the Corps may seem counterintuitive. The costs of the war, in terms of lives and limbs lost, friendships and minds shattered, would seemingly prompt disaffiliation with the Marines’ community, not deeper attachment to it. As casualties grew steadily worse, cohesion should have decreased as the gulf between costs and benefits widened. Instead, the reverse occurred: the dedication to and insularity of the Corps only grew stronger throughout the war even as the final and most violent battles exacted so high a price. When blame needed assigning, it fell almost always on other services, not on the organization that demanded so much of its members. The narratives of Marine exceptionalism continued to function, even when the service’s principal marker of difference was greater suffering and dying.

This reframing of suffering and sacrifice as devotion to one’s community is not unique to the Marine Corps. Similar cultural maneuvers exist in societies the world over and are particularly overt in religious communities. The basic cultural operation of such practices is to reconfigure a cost into a symbolic benefit, to recode pain or loss as a mark of devotion, distinction, or prestige. In the Marine Corps, these quasi-religious elements had both positive and negative attributes. They led some to sacrifice themselves unhesitatingly, but gave others a way to understand and to explain the violence and death surrounding them in the Pacific. Above all else, the Marines’ greater suffering and sacrifice gave them proof positive that their own best stories about themselves and their Corps were true.

THE NEW CORPS AND THE “DEMOCRATIC ARMY”

The Marine Corps in 1939 was small and selective, with only 1,400 officers and 18,000 enlisted men.7 Recruiters took just one of every five applicants, and many officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were already battle-hardened from fighting insurgencies in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.8 Most officers and senior enlisted men knew each other, either personally or by reputation. Marines also had a strong shared sense of place, as there were just a handful of bases, ships, and overseas stations available for assignment. Theirs was still an imagined community—no one knew everyone in the Marine Corps as they would in an actual family—but it was a tight-knit organization nonetheless, where networks of friendship and camaraderie were easy to establish.9

This culture remained cohesive during the war despite the fact that the Corps expanded to twenty times its prewar size. Even at its largest—just under 500,000 men in 1945—Marines remained connected to each other by just one or two degrees of separation.10 Two enlisted men of the same grade would have gone through one of the two recruit training depots at Parris Island, South Carolina, or San Diego, California. Officers all went through training at Quantico, Virginia, and served under the same handful of regimental and division commanders. At its largest, the Corps had just 72 general officers; the Army had more than 1,500.11

Even in the “New Corps” (as the prewar Marines called it), there was a palpable sense of elitism and community that was impossible to duplicate in the larger services. This was not an accident—whereas the other services gave more attention to ships, planes, and the machines of war, Marine recruiters specifically marketed the Corps’ traditions, history, and reputation as an all-volunteer force.12 The emphasis on elitism worked: in the first six months of the war, the Marine Corps doubled in size and had a faster rate of growth than either the Army or the Navy.13 Weekly enlistments, which had peaked at a pre–Pearl Harbor one-week high of 552, jumped to 6,000 per week.14

The all-volunteer Corps did not endure long in World War II, however. In late 1942, President Roosevelt required the War and Navy Departments to procure personnel through the Selective Service System, thus halting the Marines’ direct recruiting of draft-age men. Fortunately, President Roosevelt’s executive order pertained only to those between eighteen and thirty-five, which allowed the Marines to still enlist seventeen-year-olds. Between 1943 and 1945, the Corps recruited and enlisted 60,000 seventeen-year-old volunteers, as well as some younger than seventeen who, like Rick Spooner, forged papers.15 The Corps also staged “Marine liaisons” at the Selective Service induction centers, where they persuaded draftees to request assignment to the Marine Corps.16 As a result, of the 669,000 who served in the Marine Corps in World War II, roughly one-third came in through the Selective Service System, but only 70,000 exercised no choice in choosing the Marines.17 The rest volunteered in one way or another—either joining the Corps voluntarily before 1943 or choosing the Marines over the other branches once drafted. This system of partial choice allowed the Corps to maintain the fiction of an all-volunteer Marine Corps and to preserve its elitist image. The Army, which contained more than 70 percent draftees, could not make a similar case.18

The volunteers of 1942 and the partial volunteer system that existed thereafter made the World War II Marine Corps a self-selected group. Unlike the prewar Marine Corps, in which the South was overrepresented, World War II Marines came disproportionately from the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. The South was underrepresented.19 The most overrepresented states—Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Illinois—all had large urban populations, which tended to send more recruits to the Marines than did the more rural areas. (West Virginia was a notable exception.)20 African Americans were segregated and severely underrepresented, accounting for only 3 percent of all who served in the Corps during the war.21 Women served in equally small numbers...