![]()

1

A PERFECT MOB

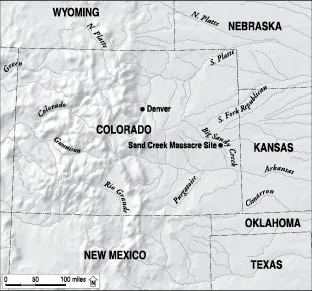

Mixed emotions transformed the ceremony into equal parts celebration and memorial service. On April 28, 2007, the National Park Service (NPS) opened the gates to its 391st unit, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. Hundreds of people gathered at a killing field tucked into the southeastern corner of Colorado. The hallowed ground sits near Eads, population 567, in Kiowa County, which, when the wind whips from the west, is within spitting distance of Kansas. In many ways Eads is typical of small towns scattered across the Great Plains: derelict historic structures line its wide main street; its fiercely proud residents love their community while worrying over its future; and a fragile agricultural economy threatens to blow away in the next drought. The massacre site, located twenty miles northeast of town, sits on a rolling prairie, a place transformed by seasons. From late summer till winter’s end, it remains a palette of browns, grays, and dusty greens: windswept soil, dry shrubs, and naked cottonwoods. In early spring through the coming of autumn, though, colors explode. Verdant buffalo and grama grasses, interspersed with orange, red, and purple wildflowers, blanket the sandy earth, and an azure sky stretches to the distant horizon. That vivid quilt had not yet draped itself over the landscape on the day of the historic site’s opening. The trees lining the creek bottom were just beginning to leaf out; it looked like the NPS had made a bulk buy of olive-drab scenery at a local army-navy surplus store.1

Colorado. (Adapted from the Sand Creek Massacre Special Resource Study, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service.)

The site’s austere beauty suited the proceedings. A Northern Arapaho drum group opened the ceremony, playing a veterans’ song as a color guard carried American and NPS flags to positions flanking the dais. A Southern Cheyenne chief named Gordon Yellowman offered an opening prayer, while other dignitaries thumbed through notes for speeches that would stretch across more than three hours. After Yellowman finished, tribal chairmen, chiefs, spiritual leaders, U.S. senators, members of Congress, governors, NPS officials, and politicians from the surrounding community mourned the dead and lauded the process that had brought the diverse crowd together. The speakers shared, some implicitly, some explicitly, their visions for what the historic site could accomplish. Save for a few exceptions, they struck an optimistic pose: protecting the Sand Creek site not only honored the memory of the people killed at the massacre, promising long-deferred “healing” for the affected tribes, but also offered a blueprint for future cooperation between Native American peoples and federal authorities. Collective remembrance, if situated in a sacred place, could seal a historical rift, cut by violence, that yawned between cultures.2

Memorials are shaped by politics. Contemporary concerns inflect how history is recalled at such places, as people engaged in the process of memorialization envision their projects with eyes cast toward the present and future as well as the past. This is especially true for federally sponsored historic sites, because government officials have long viewed public commemoration as a kind of patriotic alchemy, a way to conjure unity from divisiveness through appeals to Americans’ shared sense of history. This impulse may have been best expressed on March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln responded to secessionists, then shredding the national fabric, with his first inaugural address. In the speech’s final sentence, Lincoln implored Southerners to heed the “mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land.” Those chords, he promised, would once again “swell the chorus of the Union” when “touched … by the better angels of our nature.” At historic sites scattered across the United States, including the shrine devoted to President Lincoln that opened in Washington, DC, in 1922, sentiments like these, evincing an abiding faith in the nationalizing power of public memory, have been carved into stone. These monuments ostensibly serve the nation’s interests by linking its disparate peoples and, simultaneously, legitimating the authority of the federal government. Out of common memories, the theory goes, Americans have forged a common identity—even, Lincoln believed, as they broke into warring camps.3

Nowhere is this supposedly truer than at historic battlegrounds. At Lexington and Concord, Fort Mackinac and Chalmette, Petersburg and Shiloh, the Little Bighorn and Pearl Harbor, battlefield memorials recall the deeds of American history’s patriots, warriors who died so that the nation might live. In preserving these sites, later generations have struggled to sustain the lessons of bygone eras, connecting past and present through memory. Conservators seemingly believe that blood-soaked ground is ideally suited to this kind of didacticism, not only because of the events that transpired there but also because the landscape appears permanent, unchanging through the years, and thus capable of trapping history in amber. By walking across a wooden bridge in Boston’s exurbs, slogging through a Louisiana wetland, scaling a rocky promontory overlooking the straits connecting Lakes Michigan and Huron, descending trenches cut deep into the ground in Virginia and Tennessee, reading a list of soldiers’ names carved into a granite marker looming over a Montana prairie, or gazing at drops of oil bubbling up from the depths of the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Oahu, visitors to these sites are encouraged to stand tall against long odds, to remain steadfast in the face of privation, to rally round the flag, to practice eternal vigilance against unexpected perils, and to venerate sacred soil. Even as turbulent changes shake American society, history’s insights will remain accessible at such places. And the act of remembering, no matter how painful, will strengthen the foundation upon which the nation is built.4

Sand Creek, most speakers at the site’s opening ceremony suggested, could play this role by encouraging supplicants to set aside their disagreements in service of healing. The justification for collective remembrance in the United States in recent years has often rested on a similar assumption: that memorialization has palliative qualities. From the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City to the National September 11 Memorial in Manhattan, memorial planners have secured public support for their initiatives by promising comfort to stricken communities and the nation at large. That Sand Creek would be the first unit within the National Park System to label an event in which federal troops killed Native Americans a “massacre” promised to deepen its utility. By remembering the dead and pondering the nation’s history of racial violence, site visitors would fuel cultural pluralism’s ultimate triumph over prejudice, brokering a rapprochement between long-standing enemies. At the same time, visiting the memorial landscape would exculpate the perpetrators’ heirs, because of their willingness to mourn while admitting their forebears’ guilt in a tragedy. This utopian vision suffused most of the speeches at the opening ceremony, typifying their authors’ hopes for the historic site.5

But dissenting voices, ringing with skepticism born at Sand Creek and hardened during the tortuous process of memorializing the massacre, questioned this promise of easy diversity. These critics understood that for most of American history, whites had systematically written Native people out of the national narrative, more commonly forgetting than remembering them. For instance, most historic sites that recount the sweep of westward expansion adopt the perspective of white settlers. Given the celebratory vector of American memory projects more broadly, this is not especially surprising. In fact, few nations—the cases of South Africa and Germany are notable counterexamples—spend much time and energy remembering their sins alongside their heroic exploits. As a result, when memorials in the United States discuss Native Americans at all, they typically use them as benchmarks for national progress, as objects rather than subjects. These monuments often prop up frontier mythologies, celebrating, with imperialist rhetoric, the conquest of the American West and the dispossession of its indigenous inhabitants. Adding insult to injury, these sites regularly cast Native people as uncivilized by suggesting that they have no history of their own, that they are exclusively a people of memory. Until recently, even the NPS’s historic sites typically framed the Plains Indian Wars using the words of Robert Utley, a renowned scholar and one-time NPS chief historian, who labeled the violence a “clash of cultures.” Utley’s phrase obscured responsibility for that conflict.6

Hoping to shift that context, many of the Native people who helped to create the Sand Creek historic site rejected what they saw as a hollow offer of painless healing and quick reconciliation at the opening ceremony. Concerned that the memorial might be a stalking horse for an older assimilationist project—the U.S. government’s long-standing effort to strip tribal peoples of their distinctive identities—these skeptics instead portrayed the site as an emblem of self-determination. They understood that controlling the interpretative apparatus at a national public space, distant from the Mall in Washington, DC, but still wielding the weight of federal authority, offered them an opportunity to define insiders and outsiders. Consequently, they had fought for years to steer the commemorative process, struggling over nomenclature by insisting that the memorial be called the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. They had turned next to narration, demanding that the site tell the massacre story from a Native perspective, featuring Cheyenne and Arapaho voices informed by indigenous knowledge. Finally, they had seized the chance to root their heritage in southeastern Colorado’s landscape, reclaiming a piece of what once had been their homeland. As tribal traditionalists, they worried that modernity had besieged their way of life. They believed that the memorial would help them preserve their cultural practices, securing their future by venerating the past. For these activists, the site would serve tribal rather than federal interests.7

Other participants at the opening ceremony expressed suspicions about the memorial for a host of additional reasons: because the federal government remained unpopular on southeastern Colorado’s plains, particularly when it insinuated itself into local land-use disputes; because of the perceived taint of political correctness hovering over what some onlookers viewed as an unnecessary reinterpretation of Colorado’s history; and because of a gnawing sense that including the word “massacre” in the site’s name indicted the U.S. Army. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, with the nation embroiled in two controversial wars, some observers worried that a memorial questioning the military’s rectitude flirted with anti-Americanism.8

Kiowa County commissioner Donald Oswald served as a greeter when he spoke first at the opening ceremony. He did not mention the massacre at all, instead expressing his hope that visitors would enjoy themselves during their stay and consider returning to the area in the future. That the memorial recalled one of the great injustices in Western history stood beside the point for Oswald; he saw the site as an engine of economic growth. His remarks made sense in context. Some of his constituents had misgivings about the historic site. Their home was unusually stable, and they liked it that way. County residents often were born, raised, and died on a single piece of land. They knew their neighbors the way many Americans know their families. As Rod Brown, another county commissioner, noted, “Nobody has to use turn signals in Eads, because everybody knows where everybody else is going.” Seven in ten people residing in Kiowa County at the time had lived there for more than five years, a figure nearly 20 percent higher than for the rest of the state. The prospect of becoming a “gateway community,” hosting thousands of heritage tourists annually, thus threatened the county’s sense of itself as a quiet place, distant from the churn of urban life. Many local people also worried about tethering themselves to a service economy. They were used to being relatively independent, one of the virtues they saw in their agricultural way of life. The historic site, a sacrifice on the altar of commerce, seemed like a devil’s bargain, then. It would force change on a place fond of stasis. As Janet Frederick, head of the Kiowa County Economic Development Corporation, suggested, “there is always that fear of the unknown. It’s very comfortable here without any surprises.” But something had to give; crisis heralded compromise.9

Over the previous five years, as Colorado’s population had boomed by more than a tenth—an echo of the previous decade’s even more explosive growth—Kiowa County had experienced an exodus. Approximately 15 percent of its residents had left, usually for the promise of one of the cities, including Albuquerque, Colorado Springs, Denver, Fort Collins, and Cheyenne, sprawling up and down the Front Range. Mirroring trends found throughout the nation’s beleaguered small towns, young people especially had fled, leaving behind a rapidly aging population. Something like one in ten Coloradans were senior citizens when the Sand Creek site opened, compared to almost a quarter of Kiowa County’s residents. So when Commissioner Oswald addressed the crowd gathered at the site’s opening, he understood that if his community was not yet dying, it surely was on life support. The memorial offered a last-ditch chance to ensure that the county would have a future—even as it struggled to preserve its past.10

Still, some Kiowa County residents fretted about advertising that federal troops had perpetrated a “massacre” in their backyard. Janet Frederick, the site’s most committed local booster, explained, “people get a little defensive,” worrying that “they’re going to be looked at as the bad guys.” At the same time, she regretted that some of her neighbors found it easier “to see the cavalry and Colonel Chivington [who commanded the soldiers at Sand Creek] as more like us than the tribes are.” Frederick understood the effect of demographics: Eads was 98 percent white. She also knew that the historical bonds linking Kiowa County’s twenty-first-century residents to the violent dispossession of the Native Americans who previously had lived there could become suffocating. Again, few local people took pride in their relationship with John Chivington. But as Frederick allowed, some of them nevertheless recognized him as closer kin to them than the Cheyennes and Arapahos that his men had slaughtered in 1864.

Above all, Frederick’s participation in the public remembrance of Sand Creek had taught her about the difficulty of trying to reconcile seemingly incommensurable historical narratives. For throughout the memorialization process, competing perspectives on the massacre appeared, like restless ghosts from the past, both informing and constraining the contemporary struggle to recall the violence.11

Three massacre stories in particular still loomed over the historic site when it opened: the first from John Chivington, an enthusiastic perpetrator; the second from Silas Soule, a reluctant witness; and the third from George Bent, a victim and survivor of the ordeal. Read together, their tales suggest that so much uncertainty shrouds Sand Creek that seeking an unchallenged story of the massacre may not be merely futile, but also counterproductive. Instead, the mayhem can best be understood by sifting through conflicting, often hazy, accounts of the past. In part, discrepancies in the historical record can be ascribed to the so-called fog of war. Scenes of violence, especially mass violence, are notorious for breeding unreliable and often irreconcilable testimony. But in the case of Chivington’s, Soule’s, and Bent’s Sand Creek stories, their disagreements stemmed not only from the havoc they all experienced but also from the politics of memory surrounding the points they disputed: What caused the bloodshed? Could it have been avoided? Who should be held accountable for what happened? And was Sand Creek a glorious battle or a hideous massacre? Such questions raised thornier issues still: about the racial identities and gender ideologies that structured an emerging multicultural society in the West; about the interplay of politics and violence on the American borderlands; and, finally, about the righteousness of continental expansion and the bloody wars—both the Civil and the Indian—spawned by that process.12

Chivington, Soule, and Bent understood the stakes when they clashed over Sand Creek’s memory. And even if they could not know for certain that their dispute would reverberate across the years, they crafted and recrafted their stories, hoping to win adherents in a contest they suspected would have lasting implications. The nation, they recognized, had recently fractured over the fate of its western territories, over the question of whether federal authorities would allow slavery to root itself in that soil. The country’s future, they believed, would unfold in the same region, as white settlement stretched from the continent’s interior to the Pacific coast. Because Sand Creek took place as the Civil War raged, and because the massacre catalyzed the Indian Wars that followed, it seemed likely to be read by future generations as a pivotal chapter in the American story. Chivington, who believed that Sand Creek had been...