![]()

1 From Nakameguro to Everywhere

The top floor contained a tiny but funky recording studio crammed with Cornelius’s gadgets and trinkets: Moog synths, Maestro drum machines, guitars, a Mac, airbells, a minuscule padded live room. On one side there were views down to the cherry-lined Meguro River, on the other loomed the skyscrapers and flyovers of Shibuya. When Cornelius advertised his Point album with the slogan “From Nakameguro to everywhere,” this room was the “point” in question, the place where, day by day, the three-dimensional music got made.

—Nick Currie (Momus) (2015)

Electric Lounge

Since its launch over thirty years ago, the South by Southwest festival held annually in Austin, Texas, has earned a reputation for introducing some of the most groundbreaking musical artists on the planet to US audiences. The spring of 1998 was no exception, including the first US performance by a quiet, unassuming Japanese musician known simply as Cornelius. The show at the quaintly named Electric Lounge was reportedly packed, and included some familiar faces, notably Sean Ono Lennon. While the band’s short set didn’t proceed entirely to plan, it did not disappoint.1

Several months later, on June 11, 1998, I experienced the sensory overload at first hand at the Tribeca bar Shine in New York, one of the stops on Cornelius’s first US mini-tour. I don’t remember much about that show, other than that its animated visuals featuring Planet of the Apes characters and cute animals, and that one of the highlights was Cornelius performing a solo version of the Elvis classic “Love Me Tender” on a theremin. I do remember it as being among the most musically dazzling and exhilarating stage performances I’d ever seen.

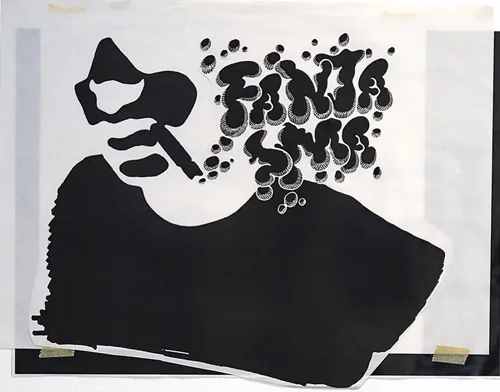

I’d picked up the CD of Cornelius’s new album, called Fantasma, a few months earlier on a friend’s recommendation, at Other Music, the tiny but uber-hip independent record store on West 4th Street, right across the street from the Tower Records megastore. At Other Music, the friend and I had already begun acquiring CDs by Japanese artists like Pizzicato Five, Kahimi Karie, Takako Minegawa, and Towa Tei, and J-pop compilations with names like Sushi 3003 and Sushi 4004. Fantasma, though, was different: its psychedelic, saturated orange cover jumped out at you from the CD racks; the cover showed a close-up graphic, presumably of the musician himself, wearing dark glasses and smoking what appeared to be a large joint whose puffs of smoke spelled out the letters of the album’s title. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Kotayama Masakazu, artwork for Fantasma cover, © Kotayama Masakazu, courtesy of 3D Corporation Ltd., Japan.

On the back, a multiple-exposure image juxtaposed multiple ghost images of the musician, flitting between the instruments scattered around his studio. (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Fantasma cover art, © 3D Corporation Ltd., courtesy of 3D Corporation Ltd., Japan.

Cornelius, I was soon to discover, was the artistic alter ego of Oyamada Keigo, a musician and producer still under thirty but already a prominent figure in the domestic Japanese music industry. In the early 1990s, Oyamada’s band Flipper’s Guitar, which he’d started with his junior high school buddy Ozawa Kenji, had spearheaded a new direction in Japanese popular music known as Shibuya-kei (the suffix kei—meaning “system” or in this context, “style”). After the breakup of Flipper’s Guitar, he had adopted the artist name of Cornelius, allegedly inspired by watching a marathon of the Planet of the Apes movies on Japanese TV. The name Cornelius itself was inspired by that of the chimpanzee archaeologist Dr. Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) in the first movie, who becomes the defender and ally of the apes’ human captive, astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston).2 The Planet of the Apes franchise had begun to take off in the mid-1970s following TV adaptations and re-runs of the original movies, with a host of merchandise and collectibles, and acquired cult status in Japan. While skipping the uncomfortable facial prosthetics endured by the actors in the movie, Cornelius and his band performed in Japan in apparel designed by another Planet of the Apes fan, Naogo Tomoaki, better known as Nigo, who in 1993 had founded a hip-hop streetwear brand called A Bathing Ape (BAPE). Cornelius live shows also featured visual imagery from the Planet of the Apes movies.

Although Matador’s release of Fantasma in 1998 was Oyamada’s first in the United States, it was actually his third album. In Japan, it had been released by Oyamada’s Trattoria label a year earlier, on the auspicious day of August 6, 1997, the fifty-second anniversary of the US bombing of Hiroshima. In subsequent months the album was performed on Oyamada’s fourth national tour, including a show in November at Tokyo’s Budōkan theater that featured a twelve-member string ensemble and half a dozen other musicians, all dressed identically to Oyamada in orange-and-white hooped sweater and dark glasses.3 The Budōkan show was attended by Chris Lombardi, whose New York–based label Matador Records had already released several CDs by Konishi Yasuharu’s band Pizzicato Five; Konishi introduced Oyamada to Lombardi, who was impressed by the Cornelius show, and Fantasma was released by Matador in the United States on March 24, 1998, and in the United Kingdom on June 11, 1998.4

Cornelius was by no means the first Japanese popular musician to gain recognition among US and European audiences. Japanese musicians have been participating in music scenes in cities like London, Paris, and New York since the Sadistic Mika Band became the first Japanese band to tour in the UK as the supporting act for Roxy Music’s 1975 tour.5 In the late 1970s the Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) toured the United States and Europe, performing on the popular TV show Soul Train, and their single “Computer Game” made the UK Top 20.6 In the 1980s, another London-based Japanese band, the duo Frank Chickens, achieved a hit single with “We Are Ninja” and recorded a session for John Peel’s radio show.7 In the 1990s, Osaka trio Shonen Knife opened for Nirvana on their UK tour and played Lollapalooza in 1994, while Pizzicato Five were signed by Matador after performing at the New York New Music Festival.

A year after its 1997 release in Japan, Fantasma was released in twenty-one countries worldwide.8 Along with artists such as Pizzicato Five, Cornelius was a major contributing factor to the international popularity of the Shibuya-kei sound, inspiring imitators both around the globe and a new generation of Japanese artists; Simon Reynolds describes it as Shibuya-kei’s “crowning achievement” (2011: 169).9 Lombardi estimates that Matador’s US release of Fantasma sold around 50,000 copies.10 In the year following its US release, Oyamada continued to tour in the United States as well as Europe, playing the Reading and Glastonbury festivals in the United Kingdom, the Roskilde festival in Denmark, and the first Coachella festival in the United States. He was also increasingly sought after for remixes by respected US and European artists: within a year, two compilation remix EPs had been released, the first featuring Oyamada’s remixes of US and European artists, the second of remixes of Fantasma by many of the same artists. Oyamada’s two subsequent albums, Point (2001) and Sensuous (2006), were released in twenty-one and nineteen countries, respectively,11 and drew considerable attention from international music critics; in addition to the United States and Europe, they were performed in two tours of Australia.12

In the years following the release of Fantasma, Oyamada collaborated with some of the most highly regarded figures in the Japanese music industry, including Sakamoto Ryūichi and Hosono Haruomi, two of the founding members of YMO; he performed with YMO at their official reunion at the World Happiness music festival in 2009, and in 2011 at the Hollywood Bowl. He also contributed to Yoko Ono’s reboot of the Plastic Ono Band both in the studio and as a sideman on its international tours.13 His induction into the pantheon of Japanese popular music was completed when he was invited to join YMO-member Takahashi Yukihiro’s latest project, the supergroup METAFIVE.

It is Fantasma that established Oyamada’s reputation, and on which it primarily rests today. More than just a landmark album, over the past decade the album has emerged as something approaching a cultural institution. In 2007, it ranked #10 in Rolling Stone Japan’s list of “100 Greatest Japanese Rock Albums of All Time” (Lindsay 2007). A three-disc boxed set was released in 2010, featuring the 1997 album remastered by Sunahara Yoshinori, a remix compilation with outtakes not included on the original album, and a DVD of concert videos and TV promos. In summer 2016, the album was reissued in the United States in a gatefold double-LP edition with both black and orange vinyl pressings. It was promoted by a six-date mini-tour in the United States. Although the album had also been released originally on vinyl—including orange vinyl—as well as CD, the re-press edition was overtly presented as a collector’s item—ironic, given that, as we will see, Fantasma was itself the outcome of Oyamada’s deep immersion in the record-collecting culture of Shibuya. The vinyl reissue and US mini-tour provided an opportunity to assess the album’s legacy and significance over the previous two decades. They proved to be only the warm-up act to the main attraction, however: the summer 2017 release of Oyamada’s first studio album in over a decade, Mellow Waves. The release of that album, in turn, provided a yardstick to measure Fantasma against, some twenty years since its release. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 Cornelius on tour in the U.S., October 2018. © 3D Corporation Ltd., courtesy of 3D Corporation Ltd., Japan. L-R: Matsumura Yumiko; Horie Hirohisa; Araki Yuko (Mi-Gu); Oyamada Keigo.

Back in 1998, Anglo-American reviewers of Fantasma were mostly impressed, albeit bemused. Rolling Stone, for example, observed that

hip-hop beats, cartoon music, shoe-gazer guitar theatrics, a reference to a “Farrah Fawcett feel-alike contest” and, again and again, Brian Wilson hommages [sic] pop in and out of earshot faster than you can say “channel-surfin’ USA.” Somehow, this qualifies as chart-topping material in Japan, where the album went multiplatinum. (Salamon 1998)

The New York Times also picked up on the album’s debt to hip-hop, describing it as “a wild blend of shiny ideas” (Ratliff 1998). A review titled “Headphone Sex” in the Village Voice described it as “pristine psychedelia” (Huston 1998). What everyone agreed on was the album’s technical wizardry, stylistic eclecticism, and wide range of references to popular music history.

Anglo-American reviewers were happy to run with the Planet of the Apes metaphor: noting that “Mr. Oyamada copies (or apes) an idea and then makes it his own,” the New York Times’ Neil Strauss (1998) described him as “primate-obsessed”:

Mr. Oyamada, in fact, has become so ape-obsessed since adopting the pseudonym Cornelius that to find out whether the law in Planet of the Apes that “Ape shall never kill ape” was true, he got in touch with a professor studying the field activities of apes. “I was disappointed to find out that monkeys actually kill each other,” he said, burrowing his head in his Bathing Ape jacket and sinking into silent reflection.14 (my emphasis)

A recent reviewer of the US reissue of Fantasma extends the metaphor to the Shibuya-kei movement in general:

Named after the Tokyo district, the music aped the orchestral flourishes of 60s pop maestros like Burt Bacharach, Serge Gainsbourg, Brian Wilson, and Phil Spector, to prod...