eBook - ePub

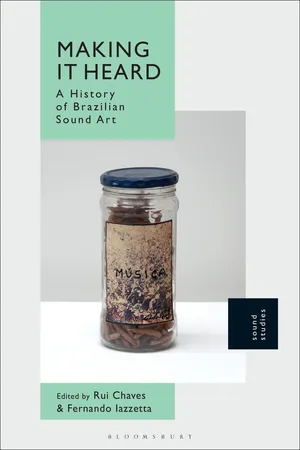

Making It Heard

A History of Brazilian Sound Art

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Making It Heard

A History of Brazilian Sound Art

About this book

From the mid-20th century to present, the Brazilian art, literature, and music scene have been witness to a wealth of creative approaches involving sound. This is the backdrop for Making It Heard: A History of Brazilian Sound Art, a volume that offers an overview of local artists working with performance, experimental vinyl production, sound installation, sculpture, mail art, field recording, and sound mapping. It criticizes universal approaches to art and music historiography that fail to recognize local idiosyncrasies, and creates a local rationale and discourse. Through this approach, Chaves and Iazzetta enable students, researchers, and artists to discover and acknowledge work produced outside of a standard Anglo-European framework.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making It Heard by Rui Chaves, Fernando Iazzetta, Rui Chaves,Fernando Iazzetta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Abre-Alas

1

Sounds from Elsewhere: Episodes for a History of Brazilian Sound Art

Where does a history begin? A discussion about sound experimentalism in Brazil starts with understanding how the forces that shaped the cultural diversity of this country, marked by miscegenation and the impact of colonialism, were constituted. It is precisely when we look at local production that we perceive the riches and contradictions that contaminate contemporary art in the country. But to speak of local production one has to get rid of the generalist speeches of a supposedly high universal culture while recognizing the diversity and the profusion of cultural contexts in a country that is about the same size as the whole of Europe.

This text seeks to provide an overview of some of the cultural and social forces that frame the environment in which Brazilian sound art has developed. It also serves as a backdrop to assist, especially the foreign reader, in contextualizing the narratives that appear in the other chapters of this book. The idea was neither to provide a linear succession of historical facts, nor to establish a causal connection between artistic-related events. Instead, I try to offer in the following pages a collection of episodes—political, cultural, and artistic—that are intermingled with the constitution of an experimental approach to sound. Creating the relationships between these episodes implies an effort toward the deconstruction of the hegemonic lines that weave the history of both music and sound art.

As with the entire Latin America and the Caribbean, our formation reflects the intertwining of two axes of forces. On the one hand, there was the imposition of a colonial will, which brought, initially from Portugal and Spain, a way of being that was acclimatized to the tropical landscapes. And, on the other hand, there was the so-called mestizo formation, in which characters of different origins amalgamated the cultural configurations of Latin America. Indigenous, European, and black peoples, more or less in that order, constituted the beginning of this miscegenation. Brazil is essentially mestizo. One only needs to walk in the streets of big cities such as São Paulo, Salvador, or Rio de Janeiro, or travel from the north to the south of the country, to experience the complex population formation. This miscegenation has already been understood as characteristic of a Brazilian generosity, of a receptivity to the other. But this desire to positivize the miscegenation process hides an uncomfortable contingency: in the first two centuries of colonization, almost all the Portuguese were men, usually very young men. The absence of women to form white families, alongside the categorical dehumanization of the indigenous people, meant that the existing social interaction was mediated by power and, literally, by force: threat and rape were at the root of the love affair that led to the intermixing of blacks and Indians with Europeans. This mixture of force and eroticism was largely confused with the relationship between repression and resistance that shaped the behavior of a culturally rich and extremely diversified population, which still suffers from one of the world’s most unequal income distributions.

Thus, in the cultural formation of Brazil, there is a constant tension generated by the proximity between rich and poor, between local and foreign, between high and low culture, between black and white, and between diversity and promiscuity. It should also be observed that, compared to most of the other countries in the region, indigenous participation took place in a particular way: less by the marked influence of these peoples in the formation of our culture, and more by the way in which we have managed to obfuscate it. From a more general perspective, the contribution of the Brazilian natives to the formation of the country was built, not by their presence but by their absence. It has been some time since they were confined to specific reservations, most of them in remote regions, existing more strikingly in the national imaginary than in the day-to-day life of the country.

And perhaps in this absence lies the first manifestation of “experimental music” in the country. Only half a century after the beginning of Portuguese domination, French merchants, wanting to attract their monarch’s attention to the commercial potential of new lands, decided to invent for France an exuberant Brazil, full of riches and bucolic landscapes. They imported some fifty indigenous people, who, together with 250 extras, exotic animals, and a scenario that reproduced the way of life of the natives, staged a “Brazilian party” during the entrance of Henry II to Rouen in 1550 on the banks of the Senna.1 The singing, dancing, and war posturing presented by the natives imported from the new continent ensnared the French monarchs and contributed to the concept of the good savage that would be developed by the French humanists, such as Montaigne in his essay “Of Cannibals” (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Despite the French costumes, this rare engraving, dated from 1613, claims to depict “true” Brazilian Indians dancing. Its title says: “These are the true portraits of the savages of the island of Maranhão called Tupinambás brought to the King of France by the Lord of Razilli. They are represented in the position they take as they dance.” Courtesy of Itaú Cultural—Coleção Olavo Setúbal. Photo by Eduoard Fraipont.

If I dwell on this somewhat anecdotal event, it is because in it I see an emblematic struggle that is common to colonized countries: the zigzag between accepting and rejecting what is local and what is foreign. This oscillation does not take place without contradictions. Nationalism, strongly present between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, for example, is revealing: while attempting to give space to aspects of the local culture (especially conferring relevance to productions considered folkloric), it presented such culture from an enlightened, literate perspective, ultimately compatible with the dominant European thinking. This process of obfuscation of what is local by a scenario that is external to it constitutes one of the dilemmas—but also one of the driving forces—of the cultural formation of Latin America.

Modernism

Brazil has built its own modernity, which has always had an ambiguous relationship with the nationalist ideal. From the late nineteenth century to the first decades of the twentieth century, this nationalism was often confused with the idealized projection of elements of the local folklore. From the 1920s onwards, there was a transition from the view of indigenous peoples as idyllic beings who inhabited bucolic landscapes, and blacks portrayed as heroes who absorbed the white morality, toward a nationalism that sought to build a national identity that would reveal the true character of the Brazilian nation. Mário de Andrade is the main character in this scenario. Writer, poet, literary critic, musicologist, and folklorist, de Andrade became a reference for the first movement for construction of a “truly” Brazilian culture. In his best-known novel, Macunaíma, o herói sem nenhum caráter (Macunaíma, the Hero with No Character [1928]), elements of folklore from various countries, fiction and reality, and high and low culture are mingled in an experimental narrative that exposes the need to have a critical stance in relation to historically marginalized groups (black, indigenous, rural, and low-income populations) and to overcome the colonial complex, freeing itself from the European referential.

The discussions put forward by this first generation of modernists (which included the poets Oswald de Andrade and Menotti del Picchia, and the painters Tarsila do Amaral and Anita Malfatti) acquired a new meaning after the Second World War, when several cultural and artistic movements grew closer to issues that seemed to be “universal.” These issues were as diverse as the exacerbated confidence in the power of science and technology and the gradual formalistic emphasis on the arts. At the same time, the comprehension of the then-current Brazilian socioeconomic reality was no longer based on ideally constructed social characters, such as the negro and the Indian (native), but on an attempt to represent the complex relationships between the actors of the social fabric. This change is related to the growing urban life and the movement of rural populations to cities.

While, in the 1950s and early 1960s, concert music was still dominated by a traditionalist stance with a nationalist inclination, it was during this period that important milestones in the country’s cultural and artistic formation were reached, reverberating in the following decades. This period coincides with the transition from the authoritarian regime of Getúlio Vargas, Estado Novo, to a more politically open phase with more progressive presidents such as Juscelino Kubitschek and, later, João Goulart.

Cinema Novo (New Cinema) was a reaction to the country’s 1950s film industry, which was dominated by chanchadas (comic, low-budget films often with erotic content), musicals, and epic films that mimicked the Hollywood aesthetics. Inspired by Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Rio Quarenta Graus (1955), a new generation of filmmakers produced scripts with a realistic approach, exploring themes such as hunger, misery, and religious alienation. For example, Deus e o diabo na terra do sol (1964), directed by Glauber Rocha, considered to be a landmark of the period, tells the story of a couple of sertanejos (people from the northeast’s backlands) who live through the drought and misery of the interior of the country. Realizing that surviving in sertão (the backlands) was no longer an option, they join a group of religious fanatics who are persecuted by the farmers of the region.

During this period, there was also an interest in design and architecture. The construction of Brasília, in a remote and sparsely inhabited region of the country, reflects in itself the significance of such areas for the country. The city, which became the capital of Brazil, was created based on an architectonic and urbanistic project of monumental dimensions. The University of Brasília was established in 1962, just two years after the city’s inauguration, and served as an important fount of knowledge and culture, whose foundations were thought by the anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro and the educator Anísio Teixeira.

In Salvador, the rector of the Federal University of Bahia brought together artists and intellectuals who would leave their mark for future generations in various fields of culture. Among them were two important names for the sound arts: the composer Hans-Joachim Koellreutter and the musician, inventor, and plastic artist Walter Smetak. In addition, there were people such as the Polish dancer Yanka Rudska, the theatre director Martim Gonçalves, the anthropologist and ethnologist Pierre Verger, and the architect Lina Bo Bardi. Bo Bardi, who designed the MASP building in São Paulo,2 also created the Museum of Modern Art of Bahia and devised a School of Industrial Design and Handicraft that followed principles similar to the Bauhaus. All this intense cultural movement would influence a generation of young Bahian artists that included names such as Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, and Glauber Rocha, who in the following years would be associated with counterculture movements and Tropicália.

Hans-Joachim Koellreutter was a prominent figure in the process of b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword: The Clash between Body and Artwork

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One Abre-Alas

- Part Two Bateria

- Part Three Barracão

- Part Four Avenida

- Part Five Batucada

- Afterword: The Audibility of Brazilian Sound Art

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Imprint