![]()

Part I

Collecting Prints

![]()

Introduction, Part I: Collecting Modern and Contemporary Prints

Britany Salsbury

“It is profoundly consequential that the maturation of the print in Western art coincides precisely with the emergence of art collecting as we now understand it.”

Peter Parshall1

The ways in which artists made prints and they were understood and collected by audiences changed dramatically during the modern and contemporary periods. With some notable exceptions, before the mid-nineteenth century, printmaking was often used in the West either for ephemera, such as caricature and broadsides, or to inexpensively copy paintings rather than to produce original works.2 As art making grew more experimental in subject and form throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so did printmaking. Art historian and curator Peter Parshall suggests that these changes in facture were directly connected to collecting.3 Collectors internationally began to see prints as an affordable way to build a sophisticated collection of contemporary art, to connect with a like-minded community of enthusiasts, and to explore the new themes and subjects of these works.

This introduction examines the history and historiography of print collecting during the modern and contemporary periods, focusing on changes in these practices during this time. It focuses primarily on the West (Europe and the United States), corresponding to my own area of expertise, although individual essays throughout this book provide a broader geographic scope. Beginning with a brief overview of collecting before the nineteenth century, it explores the ways that private and institutional collectors either adhered to or challenged these traditions, and analyzes the topic’s historiography. It argues that print collectors played a pivotal role in the way that prints were understood during this period: they were the early curators of institutional collections; they wrote much of the literature on prints and collecting; and they worked (and continue to work) to bring attention to prints as a subject of collecting and study. The introduction concludes with comments on how the process of acquiring prints has evolved in an increasingly international and online market.

Print Collecting before 1800

Prints have been collected as long as artists have made them. The earliest collectors in the West were mostly educated men of the upper classes, but their acquisitions were more practical than the product of a distinct interest in prints. In Northern Europe during the fifteenth century, collectors typically acquired intaglio prints and woodcuts to enhance the holdings of their personal libraries, pasting them throughout books as decorations or illustrations.4 Beginning in the next century, artists throughout Europe also often collected prints to use in their studios. Many of these prints reproduced paintings that were inaccessible to most audiences. Prints were copied directly by artists and provided to their students for drawing exercises, or to build knowledge of other masters. Once these study collections were assembled, they were often kept intact and passed from one generation to the next.5 The prints in them were typically purchased from religious sites such as monasteries, or later, from shops that specialized in print selling and sometimes doubled as publishers.6

Throughout Europe beginning around the late fifteenth century, collectors began more deliberately to attempt to build a unified collection. The practice evolved differently in various regions from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century. As print historian Antony Griffiths has observed, “there is no single history of print collecting, only a series of varied and linked lineages.”7 At this time, serious collectors were typically members of the aristocracy, royalty, or merchant classes, with expendable income to acquire art. They sought prints for study or entertainment, and often built massive holdings into the hundreds or even thousands during their lifetimes. Many acquired prints from established sellers in the cities in which they lived. By the eighteenth century, vendors such as the Mariette family in Paris, the Rossi family in Rome, and John Boydell in London set up popular shops that published and sold prints.8 Sometimes collectors also purchased prints while traveling to cities such as Rome to commemorate their participation in the Grand Tour.

Beginning in the eighteenth century a wider range of social classes could acquire prints due to their affordability. Middle-class collectors bought inexpensive prints to display in their homes; in England and Scotland, for example, William Hogarth’s prints were a popular choice for decoration, framed and hung in living spaces.9 In colonial Boston, the early print dealer William Price sold engraved American views, which he varnished and framed for purchase by merchants, sea captains, and government officials.10 Around 1800, print sellers in cities such as Paris and London began to feature available works in outdoor vitrines to appeal to potential collectors. Viewable in public space, these displays attracted the attention of a wide variety of social classes.

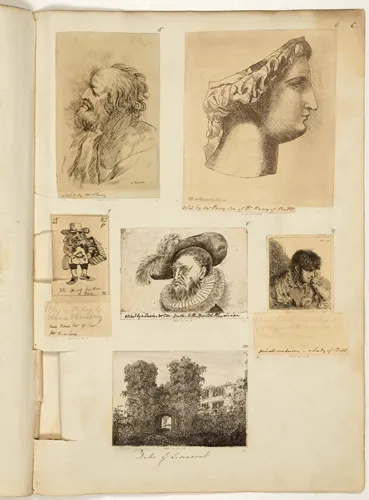

Although it varied widely, print collecting before 1800 was informally standardized with practices that continued throughout the modern and contemporary periods. Serious print collecting constituted purchasing prints by artists to build a collection rather than as decoration. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such collectors selected a theme or approach—such as the Italian school or portrait prints—and acquired as many examples as possible. They housed their collections in albums, a practice that was common until close to the nineteenth century. Each print was trimmed to the margins of its image or plate mark, pasted on a regular sized sheet, and inserted into a luxuriously bound volume. This practice can be seen in an album page from the British politician Richard Bull’s (1725–1805) collection of etchings by wealthy amateurs (Figure 0.1). Each print is affixed to the page and numbered alongside the collector’s notes. In this format, collections like Bull’s could be stored in libraries alongside books and pulled to peruse at leisure. Although this systematic approach to collecting evolved beginning in the nineteenth century, the idea of acquiring prints as objects to study and as part of a greater whole continued to define serious print collecting.11

Figure 0.1 Richard Bull’s collection of prints by amateurs, c. 1805, British Museum.

Modern Print Collecting

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, collectors began to focus more on acquiring prints because of the identity of their artist rather than their subject or relationship to a theme. In doing so, they built on the practices of serious collectors in the previous generation, although some continued to collect based on iconography or inventory. The etching revival, which began around 1850 and initiated a new and international interest in creating, marketing, and collecting original prints, was a major catalyst for this shift. Beginning in France and England, artists started to experiment with etching, which had languished in popularity since the eighteenth century. Because the technique did not require the assistance of a master printer, artists could easily learn and independently work using portable presses that fit in their studio.12 The publication of an accessible guide to etching techniques, Maxime Lalanne’s Traité de la gravure (Treatise on Etching), in 1866 inspired the growth of original printmaking internationally. Published in French and translated to English soon after, the book could be acquired by artists who were unable to travel to London or Paris to study. The art critic Charles Blanc asserted in 1880 that etchings were being made in and circulated from places as far reaching as the Hague, Poland, London, and Lisbon, suggesting the new international audience for original prints.13 And in his introduction to a translation of Lalanne’s book in the same year, Sylvester Rosa Koehler noted that “private collections have been formed and are growing in richness from day to day,” specifically citing those of King Ferdinand of Portugal and King Charles XV of Sweden, both collectors of contemporary etchings.14 This shift led to a dramatically increased market for original prints throughout Europe and the United States as the etching revival spread.

The artists who were part of the etching revival used technical aspects of their process to cultivate a sense of rarity for their works and attract collectors. By doing so, they changed how prints were collected and inspired printmakers in other media from this point forward. They began to print in growing numbers of states—variations on a single image that are achieved by revising the printing plate and continuing to pull impressions. Collectors deliberately sought out the same image in multiple states, or especially rare states. Artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler sold not only their finished prints but also working proofs, further expanding the market and the range of what could be collected.15 The use of luxury materials such as metallic inks and imported or vintage papers allowed artists to justify higher prices.16 Especially in France and England, printmakers from Francis Seymour Haden to Édouard Manet also limited their editions, sometimes designating the number of existing impressions and where an individual print fell within that process (such as, for example, 1/10) on the sheet. They routinely destroyed their plates after completing an edition, imposing an artificial limit on an inherently multiple process. These practices are still in use today by many contemporary artists.

Such aspects of r...