![]()

1

Overview

Using Business as a Force for Good Is Good for Business

Before launching into the main content of this book, it is important to get one thing clear from the start: using business as a force for good is good for business. One of the most persuasive arguments for increasing your company’s social and environmental performance is that you will save money, enhance profitability, and generate more business value. If you or others in your company, such as the CEO, CFO, or an influential board member, are skeptical about anything that hints of “green” or “socially responsible,” then this section will give you a brief snapshot of the bottom-line, business case for sustainability.

Indeed, a veritable who’s who of thought leaders such as Accenture, Deloitte, Goldman Sachs, Harvard Business School, McKinsey & Company, and PricewaterhouseCoopers have released data-driven case studies, global surveys, and exhaustive reports that offer compelling proof that using business as a force for good is good for business.

For example, Goldman Sachs reported that “more capital is now focused on sustainable business models, and the market is rewarding leaders and new entrants in a way that could scarcely have been predicted even fifteen years ago.”1 Goldman Sachs found that there has been a dramatic increase in the number of investors seeking to incorporate sustainability and environmental, social, and governance factors into their portfolio construction.

In a report that echoes this sentiment, the International Finance Corporation found that the Dow Jones Sustainability Index performed an average of 36.1 percent better than the traditional Dow Jones Index over a period of five years.2 Comparable results have been found by some of the top academic institutions in the world. For example, a recent Harvard Business School study concluded that “high sustainability companies significantly outperform their counterparts over the long term, both in terms of stock market as well as accounting performance.”3

Accenture, in a global study of CEOs’ perspectives on sustainability, found that 93 percent of CEOs see sustainability as important to their company’s future success. Accenture reported that “demonstrating a visible and authentic commitment to sustainability is especially important … to regain and build trust from the public and other key stakeholders, such as consumers and governmentstrust that was shaken by the recent global financial crisis.”4

Although some claim that sustainability is a passing trend, Deloitte stated that “sustainability is a critical business issue that is quickly becoming a mandatory requirement.”5 Deloitte went on to argue that social and environmental responsibility will continue to be relevant because, unlike other business issues, sustainability is being shaped by constituencies such as shareholders, regulators, consumers and customers, nongovernment organizations, and other drivers outside of a company’s locus of control.

If you are on the fence, PricewaterhouseCoopers found a “positive, statistically significant, linear association between sustainability and corporate financial performance,”6 and McKinsey, in no uncertain terms, said, “The choice for companies today is not if, but how they should manage their sustainability activities.” McKinsey also reported that a fragmented, reactive approach to sustainability is no longer enough. “Companies can choose to see this agenda as a necessary evil—a matter of compliance or a risk to be managed while they get on with the business of business—or they can think of it as a novel way to open up new business opportunities while creating value for society.”7

Importantly, sustainability is not just about reducing your environmental footprint. Goldman Sachs notes that “research at both the corporate and university levels suggests that this next generation of employees and consumers have specific needs at work that are dramatically different from previous generations. High among these is a desire to align personal and corporate values. To attract and retain this group, we believe that companies need to provide rewards beyond financial gain.”8

A Brief History: From AND 1 to B Corps

I first discovered the AND 1 mixtapes in the late 1990s. The mixtapes were a series of basketball “streetballing” videos, created by the popular basketball shoe and apparel company AND 1, that featured lightning-quick ball handling, acrobatic slam dunks, and jaw-dropping displays of individual talent. I was a huge fan of the AND 1 mixtapes because the players used flashy, show-off moves that were very different from the more traditional style of basketball played in college or the NBA at the time. I was so fascinated with the mixtapes that I even integrated them into my lesson plans when I worked as an English teacher in Zhejiang Province, China.

Many years later, I was quite surprised to find out that two of AND 1’s cofounders, Jay Coen Gilbert and Bart Houlahan, along with Andrew Kassoy, their longtime friend and former Wall Street private equity investor, were the people who created the Certified B Corporation (also referred to as just B Corporation, or B Corp). I learned that Gilbert’s and Houlahan’s experiences at AND 1, and Kassoy’s on Wall Street, were central to their decision to get together to start B Lab, the nonprofit behind the B Corp movement.

AND 1 was a socially responsible business before the concept was well known, although AND 1 would not have identified with the term back then. AND 1’s shoes weren’t organic, local, or made from recycled tires, but the company had a basketball court at the office, on-site yoga classes, great parental leave benefits, and widely shared ownership of the company, and each year it gave 5 percent of its profits to local charities promoting high-quality urban education and youth leadership development. AND 1 also worked with its overseas factories to implement a best-in-class supplier code of conduct to ensure worker health and safety, fair wages, and professional development.

That was quite progressive for a basketball shoe company, especially because its target consumer was teenage basketball players, not conscious consumers with a large amount of disposable income. AND 1 was a company where an employee would be happy and proud to work.

AND 1 was also successful financially. From a bootstrapped start-up in 1993 to modest revenues of $4 million in 1995, the company grew to more than $250 million in U.S. revenues by 2001. This meant that AND 1—in less than ten years—had risen to become the number two basketball shoe brand in the United States (behind Nike). As with many endeavors, however, success brought its own set of challenges.

AND 1 had taken on external investors in 1999. At the same time, the retail footwear and clothing industry was consolidating, which put pressure on AND 1’s margins. To make matters worse, Nike decided to put AND 1 in its crosshairs at its annual global sales meeting, in order to gain a larger share of the market. Not surprisingly, this combination of external forces and some internal miscues led to a dip in sales and AND 1’s first-ever round of employee layoffs. After painfully getting the business back on track and considering their various options, Gilbert, Houlahan, and their partners decided to put the company up for sale in 2005.

HOW IT ALL STARTED. The seeds of the B Corp movement were planted at a basketball company called AND 1.

The results of the sale were immediate and difficult for Gilbert and Houlahan to watch. Although the partners went into the sale process with eyes wide open, it was still heartbreaking for them to see all of the company’s preexisting commitments to its employees, overseas workers, and local community stripped away within a few months of the sale.

The Search for “What’s Next?”

In their journey from basketball (and Wall Street) to B Corps, Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy had a general sense of what they wanted to do next: the most good for as many people as possible for as long as possible. How this would manifest, however, was not initially clear.

Kassoy was increasingly inspired by his work with social entrepreneurs as a board member of Echoing Green (a venture capital firm focused on social change) and the Freelancers Insurance Company (a future Certified B Corporation). Houlahan became inspired to develop best practices to support values-driven businesses that were seeking to raise capital, grow, and hold onto their socially and environmentally responsible missions. And Gilbert, though proud of AND 1’s culture and practices, wanted to go much further, inspired by the stories of iconic socially responsible brands such as Ben & Jerry’s, Newman’s Own, and Patagonia, whose organizing principle seemed to be how to use business for good.

The three friends’ initial, instinctive answer to the “What’s next?” question was to create a new company. Although AND 1 had a lot to be proud of, they reasoned, the company hadn’t been started with a specific intention to benefit society. What if they started a company with that intention? After discussing different approaches, however, Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy decided that they would be lucky to create a business as good as those created by existing social entrepreneurs such as Ahmed and Reem Rahim from Numi Organic Tea and Mike Hannigan and Sean Marx from Give Something Back Office Supplies. And more importantly, they decided that even if they could create such a business, one more business, no matter how big and effective, wouldn’t make a dent in addressing the world’s most pressing challenges.

They then thought about creating a social investment fund. Why build one company, they reasoned, when you could help build a dozen? That idea was also short lived. The three decided that even if they could be as effective as existing social venture funds such as Renewal Funds, RSF Social Finance, or SJF Ventures, a dozen fast-growing, innovative companies was still not adequate to address society’s challenges on a large scale.

What Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy realized, after speaking with hundreds of entrepreneurs, investors, and thought leaders, was that there was a need for two basic pieces of infrastructure to accelerate the growth of—and amplify the voice of—the entire socially and environmentally responsible business sector. This existing community of leaders said they needed a legal framework to help them grow while maintaining their original mission and values, and credible standards to help them distinguish their businesses in a crowded marketplace, where everyone seemed to be making claims that they were a “good” company.

To that end, in 2006 Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy cofounded B Lab, a nonprofit organization dedicated to harnessing the power of business to solve social and environmental problems. The B Lab team worked with many of these leading businesses, investors, and attorneys to create a comprehensive set of performance and legal requirements, and they started certifying the first B Corporations in 2007.

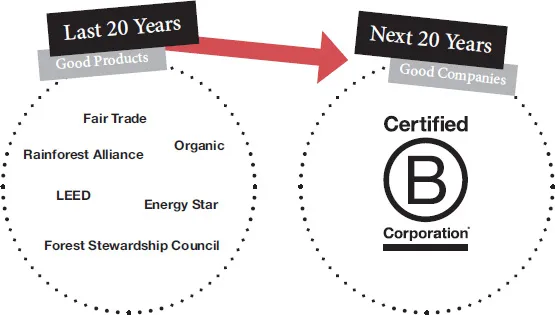

B Corps: The Quick and Dirty

Certified B Corporations are companies that have been certified by the nonprofit B Lab to have met rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. B Corp certification is similar to LEED certification for green buildings, Fair Trade certification for coffee, or USDA Organic certification for milk. A key difference, however, is that B Corp certification evaluates an entire company (e.g., worker engagement, community involvement, environmental footprint, and governance structure) rather than looking at just one aspect of a company (e.g., the building or a product). This big picture evaluation is important because it helps distinguish between good companies and just good marketing.

Today, there is a growing, global community of more than 1,000 Certified B Corporations across dozens of industries working together toward one unifying goal: to redefine success in business so that one day all companies will compete not just to be the best in the world but also to be the best for the world.

A CERTIFICATION FOR THE ENTIRE COMPANY. B Corp certification helps consumers, investors, the media, and policy makers support organizations that are using business as a force for good.

Why B Corps Matter

Business is, for better or worse, one of the most powerful forces on the planet. At its best, business encourages collaboration, innovation, and mutual well-being, and helps people to live more vibrant and fulfilling lives. At its worst, business—and the tendency to focus on maximizing short-term profits—can lead to significant social and environmental damage, such as the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill or the loss of more than $1 trillion in global wealth in the 2008 financial crisis.

Governments and nonprofits, moreover, are necessary yet insufficient to addres...