![]()

PART ONE

Only Business Can End Poverty

In these first four chapters, we’ll introduce you to your new customers and give you a bird’s-eye view of poverty as they experience it throughout the Global South. If your acquaintance with the poor is limited to what you’ve observed in one of the wealthy societies of Europe, North America, East Asia, or Australia, you’ll get a sense of how very different poverty is in most developing nations. You’ll learn why we believe poverty persists there and how the traditional approaches pursued by governments, the UN, nonprofit organizations, and philanthropists have failed to eradicate poverty during a six-decade span when the global economy has expanded 17-fold. We’ll detail the essential roles we believe government and philanthropy can nonetheless play, and we’ll explain why we’re convinced that business must be the driving force in ending poverty on a global scale.

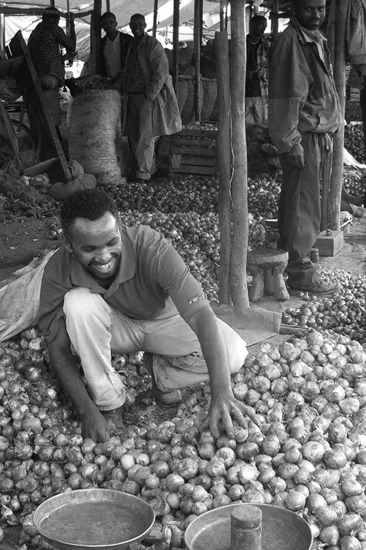

In many parts of the world, farmers sell their produce much as their ancestors did — in open-air markets like this one in Ethiopia. Prices may vary from one town to another based on strictly local circumstances, such as the scarcity of water, the dominance of a large local landowner, or variations in cultural preference or taste.

Children in poor countries are typically put to work at an early age. Most leave school before grade five. Here, children in Nepal gather firewood for sale. This girl’s family may be dependent on the additional cash her work brings in, even if her parents are healthy enough to work the long hours demanded by subsistence farming.

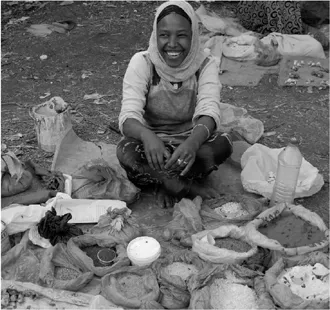

To residents of rich countries, the amounts of cash changing hands in market transactions may seem so small as to be inconsequential. However, the pennies this Ethiopian farmer earns from selling her wares on the street in town each week can make the difference between subsistence and starvation.

A restaurant can be a few pots and pans and a propane stove, as it is here in Bhopal, India. Individual entrepreneurs — more often than not migrants from villages where job opportunities are few — frequently start such businesses to generate urgently needed income to support their families. They often hire others at minimal wages to share the workload.

![]()

Chapter 1

“THE POOR ARE VERY DIFFERENT FROM YOU AND ME”

In this chapter you’ll meet your customers where they live, and you may gain new perspective on poverty as it’s experienced in developing countries.

Unless you yourself grew up in poverty in the Global South, you’ll find an environment there that may be radically different from anything you’ve experienced before. You’ll also learn that the conventional wisdom about poverty being an unrelieved misery is a myth. Here’s a taste of what you’ll encounter as you set out to establish a business to serve the poor — because, if you follow our lead, one of the first steps you take will be to venture out into the field to talk to people like those portrayed in this chapter, the people who will become your customers. These are people who constitute a marketplace to be served, with real needs to be met.

Sunil Mahapatra

As we enter the outskirts of a village in eastern India, we come across a farmer who appears to be in his early 30s. We’ll call him Sunil Mahapatra.1 Sunil lives with his wife and three children in a small mud-walled house on the east end of their village. Until recently, he and his family earned their living from one and a quarter acres of land divided into five separate fields scattered around the outskirts of the village. This includes a half-acre of monsoon-fed lowland rice. The family plants a local variety of rice, hand-broadcasting a few kilos of urea to the rice twice during the growing season. With the help of rain-fed irrigation, Sunil and his family harvested 1,300 to 1,500 pounds (600 to 700 kilos) of rice each year. Their two daughters, aged 6 and 8, and a 12-year-old son helped them keep two young goats for meat and 10 chickens. They also kept a small vegetable garden. Their dream was to someday buy a young buffalo to raise to maturity.

However, Sunil and his wife have had to scrimp and save, setting aside most of their income for the better part of a year, to provide the dowry for each of their daughters. (They hope to get at least some of this back when their son marries, especially if they can keep him in school long enough to command a good dowry.) They planned to take their daughters out of school after grade six because they couldn’t afford to pay for the school uniforms and textbooks required for later grades. Besides, the girls were needed to help with chores at home and tend to the goats and chickens. If they could improve their income from farming, they dreamed of being able to support their son all the way through high school, and then he might be able to earn enough money to help the whole family move out of poverty.

During the dry season, when he grew little in the way of crops, Sunil usually went to the city to find work. He hired on as a rickshaw puller. After he paid the rickshaw fleet owner and modest lodging and food expenses, he got to keep 50 rupees a day. With the 4,500 rupees he usually earned from rickshaw pulling, an additional 2,500 rupees from selling rice, 3,500 more from growing sunflowers, and 2,000 from his wife’s basket-making, Sunil and his family survived on 12,500 rupees in cash income each year, which amounts to about $0.70 a day. But they grew enough rice to keep the family fed for the whole year as well as monsoon vegetables to augment their diet during the six months of rainy weather.

All of this changed dramatically two years ago, when Sunil heard about a low-cost manual irrigation pump that he could use to grow a half-acre of vegetables during the dry season, when vegetable prices were two to three times as high as during rainy weather. He and his wife were able to save 250 rupees to make a down payment on a treadle pump being promoted by an organization called International Development Enterprises (IDE). They took a big gamble, borrowing 1,000 rupees from a local moneylender at an interest rate of 100 percent for four months. But Sunil was a very good farmer. By enlisting everybody in the family to pump, he could produce about 3,000 gallons (12,000 liters) of water in six hours, enough to irrigate a half-acre of vegetables in the dry season.

In the first year, Sunil and his family grew tomatoes, a high-yielding variety of eggplant, chili peppers, cucumbers, and cauliflower, which they were able to sell in the village market for an astounding 7,400 rupees (about $148). This left them with about 5,500 rupees ($110) in net profit, not counting their labor. With this, they were able to pay off the 2,000 rupees they owed the moneylender and have 3,000 rupees (about $60) more to spend.

In the second year, Sunil learned to get a better price by bringing the family’s vegetables to the market before the seasonal glut, and he cleared 6,000 rupees. The result was a total of 7,000 rupees in net additional income in the third year. With an increase of more than 50 percent in net annual income, the family has been able to put a corrugated tin roof on its house, improve its rice yield by investing in higher-yielding seeds and fertilizer, and realize its dream of raising a water buffalo.

Best of all, they now plan to keep all three of their children in school as long as they want to go. If they are good at their school-work, one of them might even have a chance to go to college!

Sunil’s Village

OK, let’s not beat the obvious to death. We’ll stipulate that (a) you’ve got a lot more money than Sunil Mahapatra (after all, he couldn’t afford to buy this book), and (b) you probably have running water, indoor plumbing, and electricity in your home, and he doesn’t. But real people’s lives can’t be summed up so simply. So, let’s drill down a little more deeply, moving in for a close-up look at the East Indian village where Sunil and his family live.

The village is located in the state of Orissa, one of dozens where an early-stage company named Spring Health (described later) has opened for business, offering safe drinking water at a very low price to villagers throughout the region. We’ll call the place Bahrimpur. It lies about 8 kilometers from the sea and halfway between Bhubeneshwar, the state capital, and the seaside city of Puri, 70 kilometers to the south.

Bahrimpur is home to 260 families. It boasts three small shops (called kirana shops) selling consumer goods such as spices, cookies, candies, and an abundance of small sachets, hanging in vertical rows, filled with products ranging from chili powder to ayurvedic (traditional Hindu) medicines to laundry detergent. The village also is home to a small tea shop and a Hindu temple.

Most of the families in Bahrimpur are Hindu, but it has a small Muslim community as well. The village also houses 30 untouchable families living across a dry streambed in a poorer section.

Bahrimpur and four nearby villages are governed by a panchayat,2 an elected body of five wise and respected elders that oversees subcommittees responsible for local roads, preschool programs, and poverty alleviation through the federal government jobs program. In Bahrimpur itself, the people of greatest influence include the village’s representative to the panchayat, the larger landowners, a school principal, and village entrepreneurs, who often run kirana shops as well as other businesses such as coconut trading and firewood.

Life in Bahrimpur takes place when the sun is up. At night, in the absence of a brilliant moon, the village is “a world lit only by fire,” to borrow the title of William Manchester’s compelling description of medieval Europe.

Seven hand pumps have been installed in the village by the government, but five of them are no longer working because when they broke, nobody in the village owned them, so nobody fixed them. One of the two pumps still working is contaminated.

The government also built two large, shallow, open wells, lined with stones. These are major community meeting points for village women, but they have no hand pumps. (It’s considered unseemly for women to walk more than 150 feet — 50 meters — or so from their homes to fetch water, but no such restriction exists for men.) Women draw up water hand over hand using ropes attached to beat-up old plastic buckets. One woman loses her bucket, and another fishes it out, cleverly using her own rope and bucket as a fishing rod. Another pours water into a tub into which she has emptied a sachet of detergent: she puts her laundry in, steps on it rhythmically with her feet, rinses it out, and carries it home in a bundle to dry. Another fills her traditional brass drinking water vessel and carries it home on her hip. But there is a problem.

When Spring Health tested the water in the two wells, both of the petri dishes in which samples from these wells were incubated displayed more than a hundred shiny, white, round colonies of E. coli, well above the standard of two or fewer for safe drinking. In fact, more than 90 percent of the more than 1,000 samples of water that people were drinking in villages like Bahrimpur in Orissa tested positive for E. coli.

A typical household of five or six in Bahrimpur includes a mother and father and three children, but brothers, grandparents, uncles, and aunts often live there as well. Two-thirds of the families living in Bahrimpur survive on less than $2 a day. One-tenth of the approximately 700 adults in the village are illiterate, and another tenth went to college. About 175 attended primary school; a smaller number, some 140, finished upper primary, and about as many finished high school.

Fewer than 10 percent of the people living in Bahrimpur use latrines. The rest use the fields, a practice euphemistically referred to as “open defecation” by public health experts. People have been doing this for years and see no reason to change. During the monsoon season, when a third of the land around the village is under water, fecal pathogens from the fields get washed into the shallow, open wells where many families obtain drinking water. These wells cost only about $75, and villagers have built a lot of them, so most people have easy access to water year-round. The end result is that the average family in Bahrimpur spends between $25 and $250 per year on medicines, oral rehydration salts, clinic visits, and, in the more severe cases, admission to the hospital to treat the illnesses they get from drinking contaminated water.

Most of the people in Bahrimpur make a living from farming. The majority of them grow subsistence crops such as rice, both to eat and to sell. Some also grow vegetables during the rainy season, mostly for home consumption. A few raise irrigated, dry-season crops. About 15 percent of the families are landless laborers who earn some income helping the larger farmers in the village plant or harvest their crops, migrate to cut sugar cane, or take seasonal construction jobs in towns and cities. Some benefit from a government-run poverty reduction program that provides about $2 a day to anyone who wants to work digging and cutting stone blocks for construction.

Now let’s meet a few more of the people who live in Bahrimpur.

Neelam Nanovati

Neelam is a widow who lives in a small thatched-roof house on the edge of Bahrimpur. Until recently, she, her husband, Ibrahim, and their two sons earned a reasonable living farming cotton on their one-and-a-half-acre farm. Then, three years ago, her husband took a large government-backed loan with the intention of doubling the cotton harvest. He planned to lease more land and take advantage of improved cotton seedlings and apply more fertilizer and pesticides. Unfortunately, an invasion of leaf spot destroyed half the crop, and he couldn’t meet the loan payments. In despair, Ibrahim hanged himself. Two years ago the family lost its land.

Neelam and her sons, aged 14 and 17, now have to survive as landless laborers. Neelam’s 17-year-old son has a seasonal job working on a farm in the neighboring state of Bihar, earning 80 rupees per day (about $1.60) on a job he expects to last two or three months. Neelam finds occasional employment as a cook. Fortunately, her younger son has a bicycle, and he secured a job with a kirana shop delivering safe water to people’s homes. For this he receives one rupee for each 10-liter jerry can he delivers. It takes him three hours and five trips to deliver 30 jerry cans each day, from which he earns a regular income of 30 rupees (about $0.60) per day.

Neelam’s family now lives on an annual income of 16,900 rupees (about $0.90 per day). This consists of 4,500 rupees earned by Neelam working 90 days at 50 rupees per day, 6,000 rupees earned by her 17-year-old son working as a farm laborer at 80 rupees per day for 80 days, and 6,000 rupees earned by her 14-year-old from delivering safe drinking water to people’s homes in Bahrimpur 200 days a year.

Although this is a little more cash income per day on average than Sunil’s family earns, Neelam’s family is landless, so they have to buy most of the food they eat, whereas Sunil’s family grows it. To make things worse, the family’s income is both irregular and unpredictable. The 90 days Neelam works and the 80 days the older son works are not just dependent on the cycle of the seasons but also on the state of their health, which could upend their lives and their hopes at any time. Only the younger son has year-round employment. To make ends meet when money runs short, which it’s sure to do several times a year, Neelam must borrow money from distant relatives, neighbors, or sometimes one of the village moneylenders.

Of course, they don’t have to pay rent for their house, which they themselves built of mud, wattle, sticks, and thatch, and they grow a few vegetab...