![]() Part I

Part I![]()

COSMOPOLIS

SPEECH

Something like human speech probably emerged at least 100,000 years ago, as a result of evolutionary developments in the brain, chest and vocal tract.1 To speak, in this most elemental meaning, is to modulate the airflow from our lungs by movements of the chest, jaw, tongue and lips, producing sequences of distinct sounds with recognisable meanings. When we say of a toddler ‘she’s talking now’, that is what she has learned to do.

A highly developed ability to communicate, involving the use of language and abstract thought, is what distinguishes human beings from our nearest relatives, such as the chimpanzee and the bonobo. The more we learn about the animal world, the more we appreciate the level of communication between dolphins or chimps. Online, you can watch videos showing the understanding of human speech achieved by the world’s most language-proficient bonobo, Kanzi, and his ability to ‘speak’ back by tapping lexigrams on a computer screen. Kanzi has reportedly learned to ‘say’ some 500 words and understand as many as 3,000. Yet, even leaving aside the fact that his chest and vocal tract do not allow him to produce sustained sequences of recognisable sounds as humans do, there is still a qualitative gulf between what Kanzi has achieved and what most human beings can express.2

Towards the end of a lifetime spent studying the animal kingdom, the broadcaster David Attenborough was asked what he found the most astonishing creature on earth. He replied: ‘The only creature that really makes my jaw sag so much that I find it hard to stop looking is a nine-month-old human baby. The rate at which it grows. The rate at which it learns. The rate at which it acquires nerves. It is the most complex and the most extraordinary of all creatures. Nothing compares to it’.3 Amongst the things it learns, like no other animal, is language. The evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar notes that by age 3 an average child can use about 1,000 words (double Kanzi’s bonobo world record); by age 6, around 13,000; and by age 18, some 60,000: ‘that means it has been learning an average of 10 new words a day since its first birthday, the equivalent of a new word every 90 minutes of its waking life’.4

Speech is not just one among many human attributes; it is a defining attribute of the human. When motor neurone disease was slowly robbing the historian Tony Judt of the power of intelligible communication, he unforgettably told me, through breaths artificially induced by a breathing machine strapped into his nostrils: ‘So long as I can communicate, I am still alive’. Pause for machine-induced breath. ‘When I can no longer communicate’—pause for machine-induced breath—‘I will no longer be alive’.5 I communicate, therefore I am.

Human communication has never been confined to speech. Physical contact, hand gestures and facial expressions must have played an important role even before chest, tongue and brain got their act together. In a sketch of what he calls Universal People, summarising what he considers anthropologically established human universals, Donald Brown dwells at length on speech and language, but includes physical gestures and the range of messages that we convey through the expressions on our faces.6

From the earliest times, we have also reached beyond our own bodies in the effort to communicate. The oldest known cave paintings have been dated to some 40,000 years ago. There is evidence of musical instruments that are probably as old and jewellery that is much older.7 These are distant predecessors of the artworks, cartoons, YouTube clips, demo placards, flag burnings, theatrical performances, songs, tattoos, forms of dress, dietary choices, Instagram and GIF pictures, Second Life avatars, emojis and myriad other contemporary forms of expression that are all embraced in the English-language phrase ‘free speech’. As the poet John Milton says in Areopagitica, his appeal for freedom from censorship in mid-seventeenth-century England, ‘what ever thing we hear or see, sitting, walking, travelling or conversing may be fitly call’d our book’.8

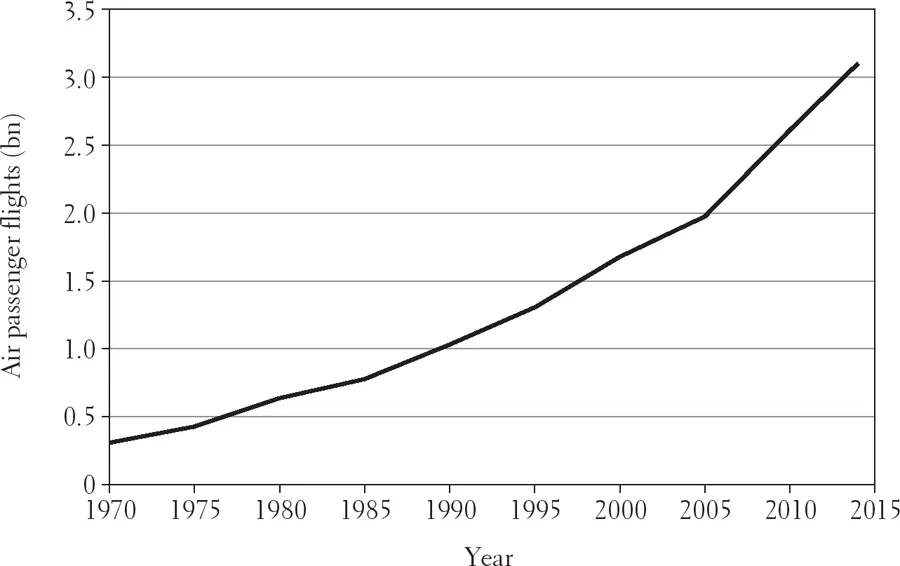

The transformed context in which the question of free speech is posed today is, however, the result of more recent developments in communication. The acceleration of communication can be tracked along two main vectors: the physical and the virtual.9 A highly selective timeline of the means human beings have found to transport themselves into physical proximity with each other could go: walk, run, swim, dugout canoe, ride on other animals, wheels, river boat, ocean-going ship, train, motor car, airplane, jet. For now, the technological advance of mass transport has paused with the jet airplane, but, as Figure 2 shows, ever more people are jetting around. In 1970, just over 300 million air passenger flights were recorded. Today, it is more than 3 billion a year, or nearly one flight for every two people on earth.10

Figure 2. Growth in air passenger flights

Source: World Development Indicators, 2014.

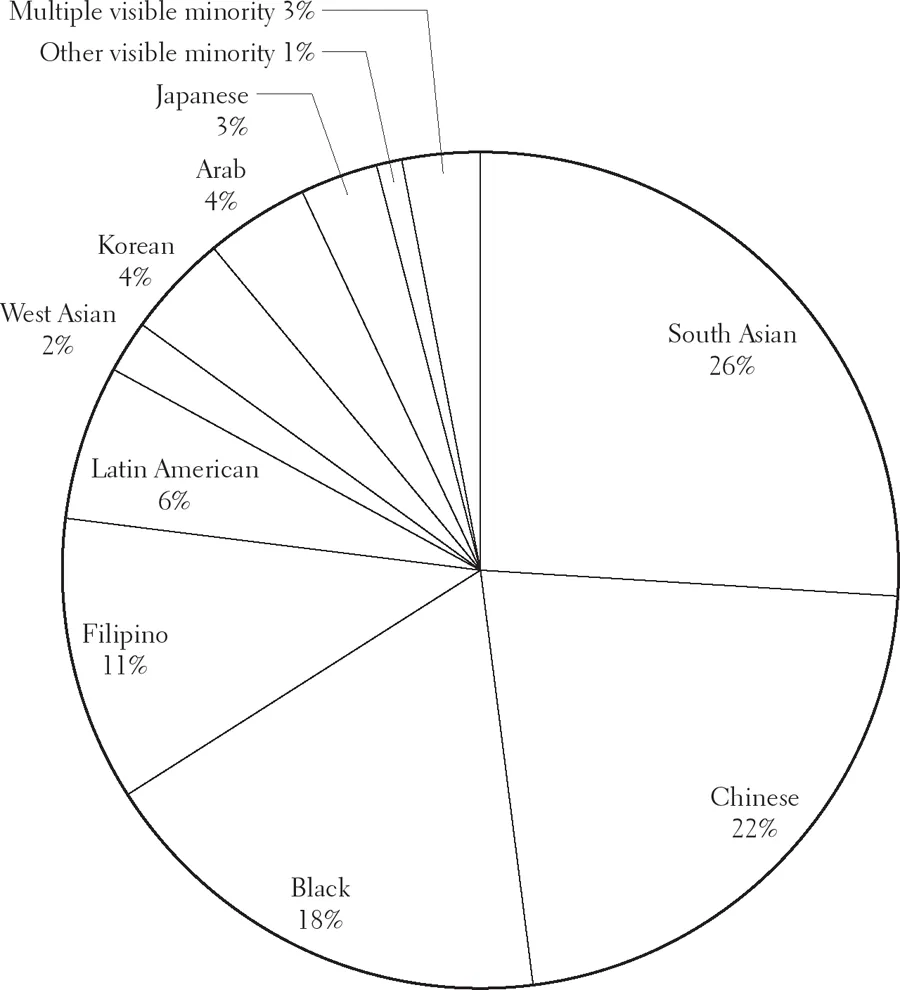

Most of those who fly are visitors, but some go to stay. A UN estimate of ‘world migrant stock’ suggests that roughly one in every 30 people has moved to a new country of residence within a single lifetime.11 A Vatican document describes this as ‘the vastest movement of people of all times’.12 Ours is now a city planet. In 2014, more than half the world’s population already lived in cities, and UN projections suggest that the world’s cities will add another 2.5 billion people by 2020.13 These will be men, women and children from everywhere, especially in the ‘megacities’ with more than 10 million inhabitants. There are already at least 25 world cities where more than one out of every four residents was born abroad, and the 2011 Canadian census revealed that an astonishing 51 percent of the population of Toronto was foreign-born.14 This is before you even get to ‘postmigrants’, the children and grandchildren of migrants. In such cities, you routinely rub shoulders with men and women from every country, culture, faith and ethnicity. Figure 3 shows the hyperdiversity of Toronto. Step into the métro, tube, U-Bahn or subway: all humankind is there.

Figure 3. Hyperdiversity: Toronto’s visible minorities

This shows the breakdown of what are counted as ‘visible minorities’, which in 2011 composed 49 percent of Toronto’s total population.

Source: Canadian National Household Survey, 2011.

Advancing technologies of physical communication did not by themselves cause this unprecedented diversity. Its deeper sources include postcolonial legacies, the impact of war, revolution and famine, a yawning economic gulf between rich global north and poor global south, the attraction of open societies and the repulsion of closed ones. Now, as 5,000 years ago, people still walk hundreds of miles and swim perilous waters in the hope of better lives for themselves and their kin. But these technologies of physical transport have made it easier for them to move.

They also enable migrants, and their postmigrant children and children’s children, to travel frequently to their own or their parents or grandparents’ country of origin: from Spain to Morocco, from Britain to Pakistan or from Australia to Vietnam.15 As important for our subject: through satellite television, the internet, email and mobile phones, migrants and postmigrants have intensive virtual contact with the people, culture and politics of their other homelands. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that, through the physical and virtual reduction of distance, they live in two countries at once.

The digital age brings both acceleration along and convergence of two previously distinct lines of communication: one-to-one and one-to-many. Key advances in the history of one individual communicating with another include the development of postal services, the telegraph, the telephone, the mobile phone, email and the smartphone. The smartphone has given access to the ‘mobile internet’, where one-to-one converges with one-to-many and all other variants, including many-to-many and many-to-one.

One-to-many has a long prehistory in the invention of writing, inscribed on tablets of stone or clay (as were, for example, the edicts of the third-century-B.C.E. Indian emperor Ashoka), on paper (in China, around the second century C.E.), the handwritten scroll and, by the third century C.E., the codex—a handwritten book with pages you turn. A great leap forward along this line was the development of printing with movable type, which was originally invented in China in the eleventh century, using ceramic type, with metal type being developed in Korea some two centuries later. However, what changed the world was the (re)discovery by the German inventor and entrepreneur Johann Gutenberg of printing with movable metal type in the 1440s, and its diffusion across Europe in the second half of the fifteenth century.16 The spread of radio and television marked another significant leap in communication from one person to many, which is the basic meaning of ‘broadcast’. (The word was originally used in nineteenth-century English to describe scattering seed by hand.) Yet there is no way round what has become a breathless commonplace: yes, the invention of the internet inaugurated the greatest advance in human communication since Gutenberg.

On 29 October 1969 a message was sent from a computer at the University of California, Los Angeles, to one at the Stanford Research Institute. What may be considered the first message of the internet age read simply ‘Lo’.17 This was not a crypto-biblical welcome to the internet as messiah (Lo! It comes!), nor the casual argot of an American cartoon character, but the result of the Stanford computer crashing before it received the final g of ‘Log’. A December 1969 map of what would eventually develop into the internet shows four computers.18 The Oxford English Dictionary dates the word ‘internet’ to 1974.19 In August 1981 there were just 213 internet hosts.20 The idea of the World Wide Web was proposed by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, and he created the first ever website at the end of 1990.21

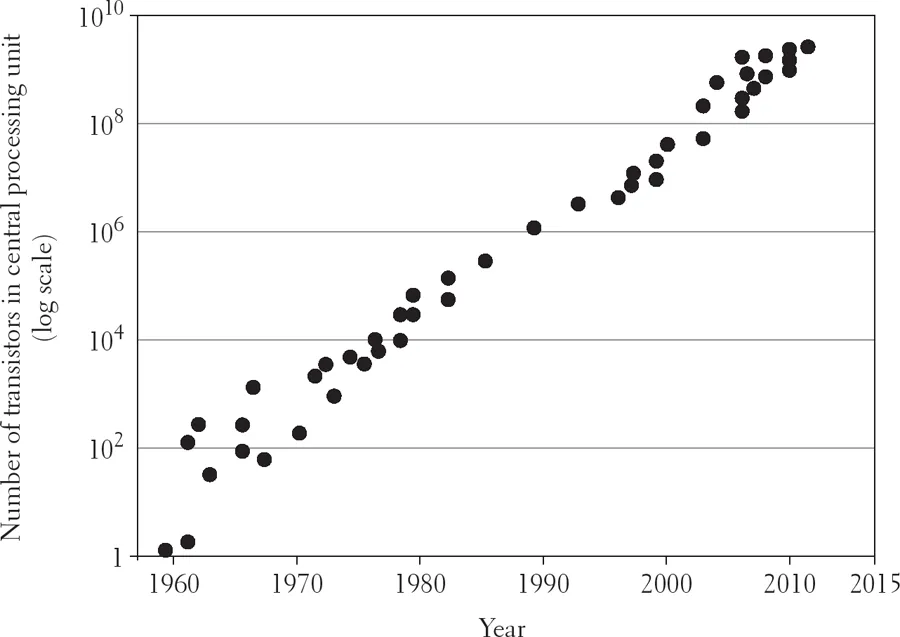

Then it was fast forward. As Figure 4 shows, what is known as ‘Moore’s Law’—predicting a regular doubling of the number of transistors you can fit on a microchip, and hence an exponential growth in computing power—has held roughly true for 50 years, since the chipmaker Gordon Moore first made that prediction in 1965, although it appears the rate of growth is now finally slowing.22

Figure 4. Moore’s Law

Source: Intel/The Economist, 2015.

New words must be coined to describe the number of bytes—the basic unit of digital memory, usually consisting of an ‘octet’ string of eight 1s and 0s—of information stored online: from the megabytes (MB, or 1,0002 bytes) and gigabytes (GB, or 1,0003 bytes) we have on our personal computers, all the way to the exabyte, zettabyte and yottabyte, or 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 individual bytes.23 According to an estimate by Cisco, it would take you about 6 million years to watch all the videos crossing global networks in a single month.24

As of 2015, there are already somewhere around 3 billion internet users, depending exactly how you define internet and user, and that number is growing rapidly.25 The fastest growth will come in the non-Western world, in wireless rather than wired and especially on mobile devices. There are perhaps 2 billion smartphones across the world and that is projected to reach 4 billion by 2020.26 Some 85 percent of the world’s population is within reach of a mobile phone tower which has the capacity to relay data. Tim Berners-Lee and Mark Zuckerberg have been among those campaigning to achieve internet access for all.27

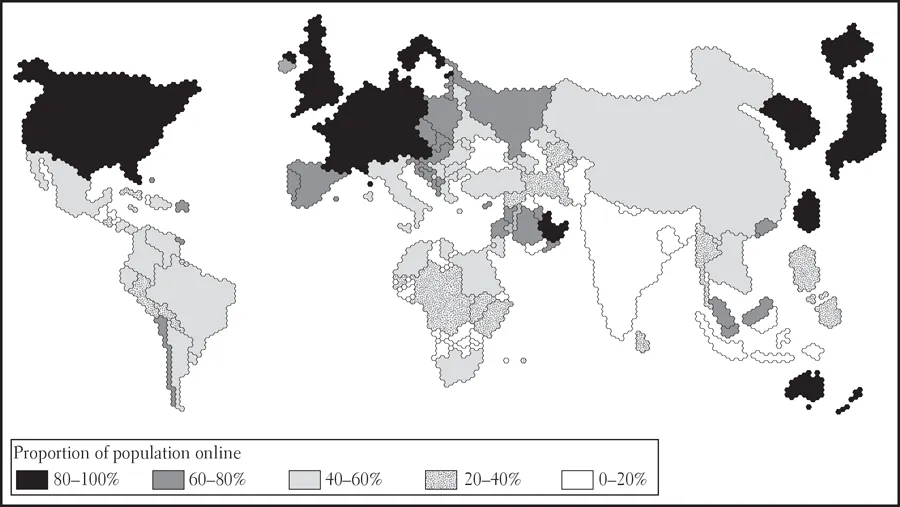

Billions of people are still excluded from this unprecedented network of communication. As Map 1 shows, internet access is very unevenly distributed across the globe.

Map 1. Unequal internet use worldwide

Country sizes are proportionate to absolute numbers of users. Countries with fewer than 470,000 people online are omitted.

Source: Oxford Internet Institute, 2013.

Even if you have regular, affordable access to the internet, which so many still do not, you need a minimum level of education to use it. According to UN estimates, some 900 million of the world’s people are still illiterate, and that is using the minimal literacy criterion that a person ‘can with understanding both read and write a short simple statement on his or her everyday life’. As can be seen from Map 2, in several African countries more than half the population is illiterate even by this minimal standard.28

Map 2. Literacy worldwide

The map shows adult literacy according to the minimal definition explained in the text.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2013.

The level of education needed to join in a wider online conversation, let alone a global one, is clearly higher than that. You also need basic facilities such as light to read by. I have neither the space nor the professional competence to examine these human development preconditions for free speech, but they are clearly vital. Thus, much of what I write in this book currently applies only to about half of humankind, although that proportion is increasing.

Technologically, however, there is no longer any reason why everyone in the world should not in future be connected with everyone else, and with almost everything known, through a small handheld box. In his satirical novel Super Sad True Love Story, Gary Shteyngart calls such a box ‘the äppärät’. (The plural, in case you were wondering, is ‘äppäräti’.)29 For our purposes, it is both futile and unnecessary to speculate, gush or moan about the next phases of this great convergence. Fortunes will be made and lost, commercial empires rise and fall, the lates...