Descriptive Research

Although some people dismiss descriptive research as ‘mere description’, good description is fundamental to the research enterprise and it has added immeasurably to our knowledge of the shape and nature of our society. Descriptive research encompasses much government sponsored research including the population census, the collection of a wide range of social indicators and economic information such as household expenditure patterns, time use studies, employment and crime statistics and the like.

Descriptions can be concrete or abstract. A relatively concrete description might describe the ethnic mix of a community, the changing age profile of a population or the gender mix of a workplace. Alternatively the description might ask more abstract questions such as ‘Is the level of social inequality increasing or declining?’, ‘How secular is society?’ or ‘How much poverty is there in this community?’

Accurate descriptions of the level of unemployment or poverty have historically played a key role in social policy reforms (Marsh, 1982). By demonstrating the existence of social problems, competent description can challenge accepted assumptions about the way things are and can provoke action.

Good description provokes the ‘why’ questions of explanatory research. If we detect greater social polarization over the last 20 years (i.e. the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer) we are forced to ask ‘Why is this happening?’ But before asking ‘why?’ we must be sure about the fact and dimensions of the phenomenon of increasing polarization. It is all very well to develop elaborate theories as to why society might be more polarized now than in the recent past, but if the basic premise is wrong (i.e. society is not becoming more polarized) then attempts to explain a non-existent phenomenon are silly.

Of course description can degenerate to mindless fact gathering or what C.W. Mills (1959) called ‘abstracted empiricism’. There are plenty of examples of unfocused surveys and case studies that report trivial information and fail to provoke any ‘why’ questions or provide any basis for generalization. However, this is a function of inconsequential descriptions rather than an indictment of descriptive research itself.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research focuses on why questions. For example, it is one thing to describe the crime rate in a country, to examine trends over time or to compare the rates in different countries. It is quite a different thing to develop explanations about why the crime rate is as high as it is, why some types of crime are increasing or why the rate is higher in some countries than in others.

The way in which researchers develop research designs is fundamentally affected by whether the research question is descriptive or explanatory. It affects what information is collected. For example, if we want to explain why some people are more likely to be apprehended and convicted of crimes we need to have hunches about why this is so. We may have many possibly incompatible hunches and will need to collect information that enables us to see which hunches work best empirically.

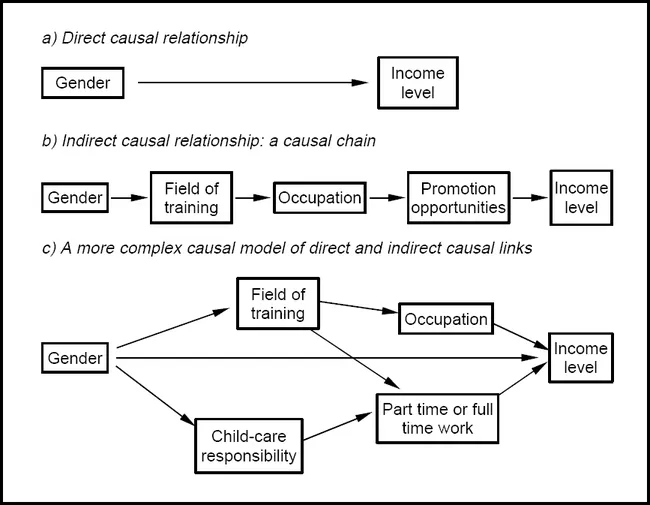

Answering the ‘why’ questions involves developing causal explanations. Causal explanations argue that phenomenon Y (e.g. income level) is affected by factor X (e.g. gender). Some causal explanations will be simple while others will be more complex. For example, we might argue that there is a direct effect of gender on income (i.e. simple gender discrimination) (Figure 1.1a). We might argue for a causal chain, such as that gender affects choice of field of training which in turn affects occupational options, which are linked to opportunities for promotion, which in turn affect income level (Figure 1.1b). Or we could posit a more complex model involving a number of interrelated causal chains (Figure 1.1c).

Figure 1.1 Three types of causal relationships

Prediction, Correlation and Causation

People often confuse correlation with causation. Simply because one event follows another, or two factors co-vary, does not mean that one causes the other. The link between two events may be coincidental rather than causal.

There is a correlation between the number of fire engines at a fire and the amount of damage caused by the fire (the more fire engines the more damage). Is it therefore reasonable to conclude that the number of fire engines causes the amount of damage? Clearly the number of fire engines and the amount of damage will both be due to some third factor - such as the seriousness of the fire.

Similarly, as the divorce rate changed over the twentieth century the crime rate increased a few years later. But this does not mean that divorce causes crime. Rather than divorce causing crime, divorce and crime rates might both be due to other social processes such as secularization, greater individualism or poverty.

Students at fee paying private schools typically perform better in their final year of schooling than those at government funded schools. But this need not be because private schools produce better performance. It may be that attending a private school and better final-year performance are both the outcome of some other cause (see later discussion).

Confusing causation with correlation also confuses prediction with causation and prediction with explanation. Where two events or characteristics are correlated we can predict one from the other. Knowing the type of school attended improves our capacity to predict academic achievement. But this does not mean that the school type affects academic achievement. Predicting performance on the basis of school type does not tell us why private school students do better. Good prediction does not depend on causal relationships. Nor does the ability to predict accurately demonstrate anything about causality.

Recognizing that causation is more than correlation highlights a problem. While we can observe correlation we cannot observe cause. We have to infer cause. These inferences however are ‘necessarily fallible … [they] are only indirectly linked to observables’ (Cook and Campbell, 1979: 10). Because our inferences are fallible we must minimize the chances of incorrectly saying that a relationship is causal when in fact it is not. One of the fundamental purposes of research design in explanatory research is to avoid invalid inferences.

Deterministic and Probabilistic Concepts of Causation

There are two ways of thinking about causes: deterministically and probabilistically. The smoker who denies that tobacco causes cancer because he smokes heavily but has not contracted cancer illustrates deterministic causation. Probabilistic causation is illustrated by health authorities who point to the increased chances of cancer among smokers.

Deterministic causation is where variable X is said to cause Y if, and only if, X invariably produces Y. That is, when X is present then Y will ‘necessarily, inevitably and infallibly’ occur (Cook and Campbell, 1979: 14). This approach seeks to establish causal laws such as: whenever water is heated to 100 °C it always boils.

In reality laws are never this simple. They will always specify particular conditions under which that law operates. Indeed a great deal of scientific investigation involves specifying the conditions under which particular laws operate. Thus, we might say that at sea level heating pure water to 100 °C will always cause water to boil.

Alternatively, the law might be stated in the form of ‘other things being equal’ then X will always produce Y. A deterministic version of the relationship between race and income level would say that other things being equal (age, education, personality, experience etc.) then a white person will [always] earn a higher income than a black person. That is, race (X) causes income level (Y).

Stated like this the notion of deterministic causation in the social sciences sounds odd. It is hard to conceive of a characteristic or event that will invariably result in a given outcome even if a fairly tight set of conditions is specified. The complexity of human social behaviour and the subjective, meaningful and voluntaristic components of human behaviour mean that it will never be possible to arrive at causal statements of the type ‘If X, and A and B, then Y will always follow.’

Most causal thinking in the social sciences is probabilistic rather than deterministic (Suppes, 1970). That is, we work at the level that a given factor increases (or decreases) the probability of a particular outcome, for example: being female increases the probability of working part time; race affects the probability of having a high status job.

We can improve probabilistic explanations by specifying conditions under which X is less likely and more likely to affect Y. But we will never achieve complete or deterministic explanations. Human behaviour is both willed and caused: there is a double-sided character to human social behaviour. People construct their social world and there are creative aspects to human action but this freedom and agency will always be constrained by the structures within which people live. Because behaviour is not simply determined we cannot achieve deterministic explanations. However, because behaviour is constrained we can achieve probabilistic explanations. We can say that a given factor will increase the likelihood of a given outcome but there will never be certainty about outcomes.

Despite the probabilistic nature of causal statements in the social sciences, much popular, ideological and political discourse translates these into deterministic statements. Findings about the causal effects of class, gender or ethnicity, for example, are often read as if these factors invariably and completely produce particular outcomes. One could be forgiven for thinking that social science has demonstrated that gender completely and invariably determines position in society, roles in families, values and ways of relating to other people.