![]()

Chapter 1

The Cornerstones of Survey Research

Edith D. de Leeuw

Joop J. Hox

Department of Methodology & Statistics, Utrecht University

Don A. Dillman

Washington State University

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The idea of conducting a survey is deceptively simple. It involves identifying a specific group or category of people and collecting information from some of them in order to gain insight into what the entire group does or thinks; however, undertaking a survey inevitably raises questions that may be difficult to answer. How many people need to be surveyed in order to be able to describe fairly accurately the entire group? How should the people be selected? What questions should be asked and how should they be posed to respondents? In addition, what data collection methods should one consider using, and are some of those methods of collecting data better than others? And, once one has collected the information, how should it be analyzed and reported? Deciding to do a survey means committing oneself to work through a myriad of issues each of which is critical to the ultimate success of the survey.

Yet, each day, throughout the world, thousands of surveys are being undertaken. Some surveys involve years of planning, require arduous efforts to select and interview respondents in their home and take many months to complete and many more months to report results. Other surveys are conducted with seemingly lightning speed as web survey requests are transmitted simultaneously to people regardless of their location, and completed surveys start being returned a few minutes later; data collection is stopped in a few days and results are reported minutes afterwards. Whereas some surveys use only one mode of data collection such as the telephone, others may involve multiple modes, for example, starting with mail, switching to telephone, and finishing up with face-to-face interviews. In addition, some surveys are quite simple and inexpensive to do, such as a mail survey of members of a small professional association. Others are incredibly complex, such as a survey of the general public across all countries of the European Union in which the same questions need to be answered in multiple languages by people of all educational levels.

In the mid-twentieth century there was a remarkable similarity of survey procedures and methods. Most surveys of significance were done by face-to-face interviews in most countries in the world. Self-administered paper surveys, usually done by mail, were the only alternative. Yet, by the 1980s the telephone had replaced face-to-face interviews as the dominate survey mode in the United States, and in the next decade telephone surveys became the major data collection method in many countries. Yet other methods were emerging and in the 1990s two additional modes of surveying—the Internet and responding by telephone to prerecorded interview questions, known as Interactive Voice Response or IVR, emerged in some countries. Nevertheless, in some countries the face-to-face interview remained the reliable and predominantly used survey mode.

Never in the history of surveying have their been so many alternatives for collecting survey data, nor has there been so much heterogeneity in the use of survey methods across countries. Heterogeneity also exists within countries as surveyors attempt to match survey modes to the difficulties associated with finding and obtaining response to particular survey populations.

Yet, all surveys face a common challenge, which is how to produce precise estimates by surveying only a relatively small proportion of the larger population, within the limits of the social, economic and technological environments associated with countries and survey populations in countries. This chapter is about solving these common problems that we described as the cornerstones of surveying. When understood and responded to, the cornerstone challenges will assure precision in the pursuit of one’s survey objectives.

1.2 WHAT IS A SURVEY?

A quick review of the literature will reveal many different definitions of what constitutes a survey. Some handbooks on survey methodology immediately describe the major components of surveys and of survey error instead of giving a definition (e.g., Fowler, Gallagher, Stringfellow, Zalavsky Thompson & Cleary, 2002, p. 4; Groves, 1989, p. 1), others provide definitions, ranging from concise definitions (e.g., Czaja & Blair, 2005, p. 3; Groves, Fowler, Couper, Lepkowski, Singer & Tourangeau, 2004, p. 2; Statistics Canada, 2003, p. 1) to elaborate descriptions of criteria (Biemer & Lyberg, 2003, Table 1.1). What have these definitions in common? The survey research methods section of the American Statistical Association provides on its website an introduction (Scheuren, 2004) that explains survey methodology for survey users, covering the major steps in the survey process and explaining the methodological issues. According to Scheuren (2004, p. 9) the word survey is used most often to describe a method of gathering information from a sample of individuals. Besides sample and gathering information, other recurring terms in definitions and descriptions are systematic or organized and quantitative. So, a survey can be seen as a research strategy in which quantitative information is systematically collected from a relatively large sample taken from a population.

Most books stress that survey methodology is a science and that there are scientific criteria for survey quality. As a result, criteria for survey quality have been widely discussed. One very general definition of quality is fitness for use. This definition was coined by Juran and Gryna in their 1980s book on quality planning and analysis, and has been widely quoted since. How this general definition is further specified depends on the product that is being evaluated and the user. For example, quality can be focusing on construction, on making sturdy and safe furniture, and on testing it. Like Ikea, the Swedish furniture chain, that advertised in its catalogs with production quality and gave examples on how a couch was tested on sturdiness. In survey statistics the main focus has been on accuracy, on reducing the mean squared error or MSE. This is based on the Hansen and Hurwitz model (Hansen, Hurwitz, & Madow, 1953; Hansen, Hurwitz, & Bershad, 1961) that differentiates between random error and systematic bias, and offers a concept of total error (see also Kish, 1965), which is still the basis of current survey error models. The statistical quality indicator is thus the MSE: the sum of all squared variable errors and all squared systematic errors. A more modern approach is total quality, which combines both ideas as Biemer and Lyberg (2003) do in their handbook on survey quality. They apply the concept of fitness for use to the survey process, which leads to the following quality requirements for survey data: accuracy as defined by the mean squared error, timeliness as defined by availability at the time it is needed, and accessibility, that is the data should be accessible to those for whom the survey was conducted.

There are many stages in designing a survey and each influences survey quality. Deming (1944) already gave an early warning of the complexity of the task facing the survey designer, when he listed no less than thirteen factors that affect the ultimate usefulness of a survey. Among those are the relatively well understood effects of sampling variability, but also more difficult to measure effects. Deming incorporates effects of the interviewer, method of data collection, nonresponse, questionnaire imperfections, processing errors and errors of interpretation. Other authors (e.g., Kish, 1965, see also Groves, 1989) basically classify threats to survey quality in two main categories, for instance differentiating between errors of nonobservation (e.g., nonresponse) and observation (e.g., in data collection and processing). Biemer and Lyberg (2003) group errors in sampling error and nonsampling error. Sampling error is due to selecting a sample instead of studying the whole population. Nonsampling errors are due to mistakes and/or system deficiencies, and include all errors that can be made during data collection and data processing, such as coverage, nonresponse, measurement, and coding error (see also Lyberg & Biemer, Chapter 22).

In the ensuing chapters of this handbook we provide concrete tools to incorporate quality when designing a survey. The purpose of this chapter is to sensitize the reader to the importance of designing for quality and to introduce the methodological and statistical principles that play a key role in designing sound quality surveys.

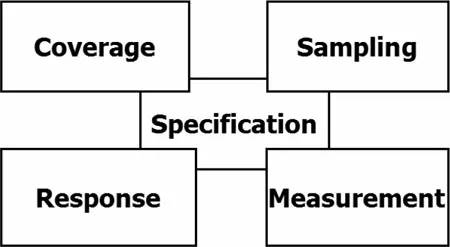

A useful metaphor is the design and construction of a house. When building a house, one carefully prepares the ground and places the cornerstones. This is the foundation on which the whole structure must rest. If this foundation is not designed with care, the house will collapse or sink in the unsafe, swampy underground as many Dutch builders have experienced in the past. In the same way, when designing and constructing a survey, one should also lay a well thought-out foundation. In surveys, one starts with preparing the underground by specifying the concepts to be measured. Then these clearly specified concepts have to be translated, or in technical terms, operationalized into measurable variables. Survey methodologists describe this process in terms of avoiding or reducing specification errors. Social scientists use the term construct validity: the extend to which a measurement method accurately represents the intended construct. This first step is conceptual rather than statistical; the concepts of concern must be defined and specified. On this foundation we place the four cornerstones of survey research: coverage, sampling, response, and measurement (Salant & Dillman, 1994; see also Groves, 1989).

Figure 1.1 The cornerstones of survey research

Figure 1.1 provides a graphical picture of the cornerstone metaphor. Only when these cornerstones are solid, high quality data are collected, which can be used in further processing and analysis. In this chapter we introduce the reader to key issues in survey research.

1.3 BREAKING THE GROUND: SPECIFICATION OF THE RESEARCH AND THE SURVEY QUESTIONS

The first step in the survey process is to determine the research objectives. The researchers have to agree on a well-defined set of research objectives. These are then translated into a set of key research questions. For each research question one or more survey questions are then formulated, depending on the goal of the study. For example, in a general study of the population one or two general questions about well-being are enough to give a global indication of well-being. On the other hand, in a specific study of the influence of social networks on feelings of well-being among the elderly a far more detailed picture of wellbeing is needed and a series of questions has to be asked, each question measuring a specific aspect of well-being. These different approaches are illustrated in the text boxes noted later.

Example General Well-being Question (Hox, 1986)

Taking all things together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with life in general?

□ VERY DISSATISFIED

□ DISSATISFIED

□ NEITHER DISSATISFIED, NOR SATISFIED

□ SATISFIED

□ VERY SATISFIED

Examples General + Specific Well-being Questions (Hox, 1986)

Taking all things together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with life in general?

□ VERY DISSATISFIED

□ DISSATISFIED

□ NEITHER DISSATISFIED, NOR SATISFIED

□ SATISFIED

□ VERY SATISFIED

Taking all things together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the home in which you live?

□ VERY DISSATISFIED

□ DISSATISFIED

□ NEITHER DISSATISFIED, NOR SATISFIED

□ SATISFIED

□ VERY SATISFIED

Taking all things together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your health?

Taking all things together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your social contacts?

Survey methodologists have given much attention to the problems of formulating the actual questions that go into the survey questionnaire (cf. Fowler & Cosenza, Chapter 8). Problems of question wording, questionnaire flow, question context, and choice of response categories have been the focus of much attention. Much less attention has been directed at clarifying the problems that occur before the first survey question is committed to paper: the process that leads from the theoretical construct to the prototype survey item (cf. Hox, 1997). Schwarz (1997) notes that large-scale survey programs often involve a large and heterogeneous group of researchers, where the set of questions finally agreed upon is the result of complex negotiations. As a result, the concepts finally adopted for research are often vaguely defined.

When thinking about the process that leads from theoretical constructs to survey questions, it is useful to distinguish between conceptualization and operationalization. Before questions can be formulated, researchers must decide which concepts they wish to measure. They must define they intend to measure by naming the concept, describing its properties and its scope, and defining important subdomains of its meaning. The subsequent process of operationalization involves choosing empirical indicators for each concept or each subdomain. Theoretical concepts are often referred to as ‘constructs’ to emphasize that they are theoretical concepts that have been invented or adopted for a specific scientific purpose (Kerlinger, 1986). Fowler and Cosenza’s (Chapter 8) discussion of the distinction between constructs and survey questions follows these line of reasoning.

To bridge the gap between theory and measurement, two distinct research strategies are advocated: a theory driven or top down strategy, which starts with constructs and works toward observable variables and a data driven or bottom up strategy, which starts with observations and works towards theoretical constructs (cf. Hox & De Jong-Gierveld, 1990). For examples of such strategies we refer to Hox (1997).

When a final survey question as posed to a respondent fails to ask about what is essential for the research question, we have a specification error. In other words, the construct implied in the survey question differs from the intended construct that should be measured. This is also referred to as a measurement that has low construct validity. As a result, the wrong parameter is estimated and the research objective is not met. A clear example of a specification error is given by Biemer and Lyberg (2003, p. 39). The intended concept to be measured was “…the value of a parcel of land if it were sold on a fair market today.” A potential operationalization in a survey question would be “For what price would you sell this parcel of land?” Closer inspection of this question reveals that this question asks what the parcel of land is subjectively worth to the farmer. Perhaps it is worth so much to the farmer that she/he would never sell it at all.

There are several ways in which one can investigate whether specification errors occur. First of all, the questionnaire outline and the concept questionnaire should always be thoroughly discussed by the researchers, and with the client or information users, and explicit checks should be made whether the questions in the questionnaire reflect the study objectives. In the next step, the concept questionnaire should be pretested with a small group of real respondents, using so called cognitive lab methods. These are qualitative techniques to investigate whether and when errors occur in the question-answer process. The first step in the question answer process is understanding the question. Therefore, the first thing that is investigated in a pretest is if the respondents understand the question and the words used in the question as intended by the researcher. Usually questions are adapted and/or reformulated, based on the results of questionnaire pretests. For a good description of pretesting, methods, see Campanelli . Whenever a question is reformulated, there is the danger of changing its original (intended) meaning, and thus introducing a new specification error. Therefore, both the results of the pretests and the final adapted questionnaire should again be thoroughly discussed with the client.

1.4 PLACING THE CORNERSTONES: COVERAGE, SAMPLING, NONRESPONSE, AND MEASUREMENT

As noted earlier, specification of the research question and the drafting of prototype survey questions are conceptual rather t...