![]()

Chapter 1

Contents

The emergence of social neuroscience

The social brain?

Is neuroscience an appropriate level of explanation for studying social behavior?

Overview of subsequent chapters

Summary and key points of the chapter

Example essay questions

Recommended further reading

Online Resources

Introduction to social neuroscience | 1 |

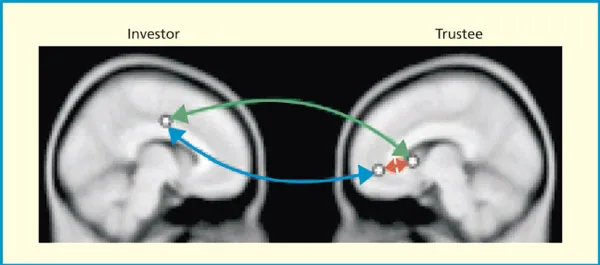

Imagine two participants lying in different rooms, each with their heads placed in a very large magnetic field. Crucially, the two participants are interacting with each other in order to win money and this interaction requires trust. By trusting money to the other person they stand a greater chance of getting more money returned to them in the future, but they also run the risk of exploitation. As their brains engage in the decision to trust or not to trust, there are subtle changes in blood flow corresponding to these different decisions that can be detected. The fact that different patterns of thought should result in different patterns of brain activity is perhaps not surprising. The fact that we now have methods that can attempt to measure this is certainly noteworthy. What is most interesting about studies such as these is the fact that activity in regions of one person’s brain can reliably elicit activity in other regions of another person’s brain during this social interaction. For instance, in a trusting relationship, when one person makes a decision the other person’s brain ‘lights up’ their reward pathways, even before any reward is actually obtained – as illustrated in Figure 1.1 (King-Casas et al., 2005). Cognition in an individual brain is characterized by a network of flowing signals between different regions of the brain. However, social interactions between different individuals can be characterized by the same principle: a kind of ‘mega-brain’ in which different regions in different brains can have mutual influence over each other. This is not caused by a physical flow of activity between brains (as happens between different regions in the same brain) but by our ability to perceive, interpret, and act on the social behavior of others.

Figure 1.1 The technique of hyperscanning records from two or more different brains simultaneously (such as MRI scanners): for example, whilst participants in the scanners engage in a social activity (Montague et al., 2002). The details of this particular study, involving a game of trust, are not important here (they are covered in Chapter 7) and hyperscanning is a relatively rare methodology. What is of interest is that neural activity in different regions correlates not only within the same brain (due to physical connections; depicted in red) but also across brains (due to mutual understanding; depicted in blue and green). From King-Casas et al. (2005). Copyright © 2005 American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reproduced with permission.

Key term

Hyperscanning

The simultaneous recording from two or more different brains (e.g. using fMRI or EEG)

This introductory chapter will begin by providing a brief overview of the (brief) history of social neuroscience. It will then go on to consider what kind of mechanisms could constitute the ‘social brain’ and how they might relate to nonsocial brain processes. Finally, it will consider how different levels of explanation are needed to derive a complete understanding of social behavior, and it will discuss how neuroscience can be combined with other approaches.

Key terms

Social psychology

An attempt to understand and explain how the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others.

Cognitive psychology

The study of mental processes such as thinking, perceiving, speaking, acting, and planning.

The emergence of social neuroscience

Allport (1968) defined social psychology as ‘an attempt to understand and explain how the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others’. By extension, a reasonable working definition of social neuroscience would be:

an attempt to understand and explain, using neural mechanisms, how the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others.

Based on this definition, one could regard social neuroscience as being a subdiscipline within social psychology that is distinguished only by its adherence to neuroscientific methods and/or theories. Whilst this may be perfectly true, most researchers working within the field of social neuroscience do not have backgrounds within social psychology but tend to be drawn from the fields of cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Indeed social neuroscience has also gone by the name ‘social cognitive neuroscience’ (the term is less commonly used now). Cognitive psychology is the study of mental processes such as thinking, perceiving, speaking, acting, and planning. It tends to dissect these processes into different sub-mechanisms and explain complex behavior in terms of their interaction. Cognitive psychology has an important role to play in social neuroscience because it aims to decompose complex social behaviors into simpler mechanisms (operating in individual minds) that are amenable for exploration using neuroscientific methodologies. Social neuroscience links together all these disciplines: linking cognitive and social psychology, and linking ‘mind’ (psychology) with brain (biology, neuroscience). Of course, these divisions themselves are arbitrary. They serve as convenient ways of categorizing research programs, and they become embedded in the way they are taught (lecture courses, textbooks, etc.).

The term social neuroscience can be traced to an article by Cacioppo and Berntson (1992) entitled ‘Social psychological contributions to the decade of the brain: Doctrine of multi-level analysis’. The term appears twice: once in a footnote, and once in a heading accompanied by a question mark – i.e. ‘Social Neuroscience?’. Their particular interest in the topic stemmed from research showing that psychological processes such as perceived social support can affect immune functioning. However, many other areas of study that now fall under the social neuroscience umbrella were already active areas of study prior to 1992. In cognitive psychology, there was a mature literature on face perception. However, this literature was primarily concerned with understanding faces as a type of visual object rather than treating faces as cues to social interactions. There were also detailed accounts of how social behavior breaks down as a result of acquired brain damage (Damasio, Tranel, & Damasio, 1990; Eslinger & Damasio, 1985) or in developmental conditions such as autism (e.g. Frith, 1989). In behavioral neuroscience, there was a longstanding interest in emotional processes such as fear (e.g. LeDoux, Iwata, Cicchetti, & Reis, 1988), aggression (e.g. Siegel, Roeling, Gregg, & Kruk, 1999), and separation distress (e.g. Panksepp, Herman, Vilberg, Bishop, & DeEskinazi, 1980). In social psychology, the field of ‘social cognition’ applied the approach and methods of cognitive psychology (e.g. response time) to social psychology questions. Finally, the 1990s saw the refinement of the newly established methods of cognitive neuroscience, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and these methods were directed to social processes as well as to the more traditional areas within cognitive psychology.

By the year 2000, social neuroscience could be recognized as a relatively coherent entity with a core set of research issues and methods and as reflected in prominent reviews of the time (e.g. Adolphs, 1999; Frith & Frith, 1999; Ochsner & Lieberman, 2001). The first journals dedicated to this field, Social Neuroscience and Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (SCAN), both appeared in 2006. The Society for Social and Affective Neuroscience (SANS; www.socialaffectiveneuro.org) and Society for Social Neuroscience (S4SN; www.s4sn.org) were established in 2008 and 2010 respectively. Both societies welcome student members. The first edition of this textbook, published in 2012, was the first single-authored study guide aimed at undergraduate students.

Stanley and Adolphs (2013, p. 822) provide a compelling summary of the current state of the field and point to its future evolution. They summarize it as follows:

Although we have moved from regions to networks, the next key step is to identify the flow of information through these networks to follow social information processing from stimulus through to response. This requires an understanding of the detailed computations implemented by the different nodes in the networks as well the dynamic interplay between them. One could make the analogy of moving from words (brain areas) to sentences (networks) to propositions (arrangements of network dynamics) to conversations (brains interacting). We are still solidly in the age of sentences and are only beginning to enter the age of propositions and conversations.

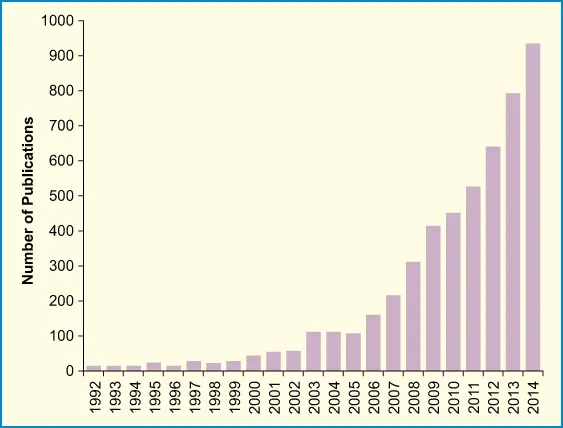

Figure 1.2 The number of publications incorporating the term ‘social’ and ‘neuroscience’ has increased dramatically since 2000. This data is based on a search of the Web-of-Knowledge database searching for a conjunction of ‘social’ and ‘neuroscience’ in the topic field.

Many of these ideas are explored in more detail throughout the chapter and, indeed, the book. Can we assign unique functions to brain regions or use activity in a given brain region to infer the nature of information processing (e.g. emotional versus rational)? Are there brain regions or networks that can be understood specifically in terms of their contribution to social functioning or do these regions/networks also participate in similar ways in non-social cognition? How can social neuroscience study realistic social interactions? On the latter point, Schilbach et al. (2013) have pointed out that most previous research in social neuroscience has tended to involve observing and interpreting other people and that the neural mechanisms underlying social interactions per se can (metaphorically) be considered the ‘dark matter’ of social neuroscience. Complementary to this, Willingham and Dunn (2003, p. 669) cautioned social psychologists against changing their research agenda just to make them amenable to a neuroimaging approach:

Some of the topics of interest to social psychologists are not amenable to brain localization techniques because of the complexity of the processes; they have embedded in them subprocesses that interact, and such complex processes are difficult to localize. It would be a pity if, in their justifiable enthusiasm for this powerful tool [i.e. neuroimaging], social psychologists subtly shifted their research programs to problems that are amenable to brain localization or shifted their theoretical language to constructs that are localizable.

What should we make of criticism such as this? Willingham and Dunn (2003) are correct to point out that it is important not to shift the whole social psychology research agenda to fit with trendy neuroscience methods. To a large extent, the shift has to come from the development of neuroscientific techniques that can tackle the questions that matter. However, their characterization of social neuroscience in terms of localization of functions is inaccurate (or, at least, outdated). Social neuroscience should be concerned primarily with the underlying mechanisms, and these are unlikely to be localized to discrete brain regions.

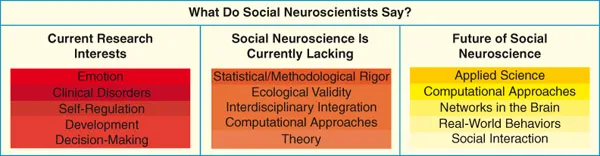

Stanley and Adolphs (2013) also report a number of surveys conducted on Social Neuroscience researchers attending international conferences. Figure 1.3 shows a summary of a survey asking researchers what they presently work on, what is presently lacking in the field, and what the future of social neuroscience will consist of. Current researchers tend to work on topics such as emotion, self-regulation, and decision-making but feel that the discipline as a whole needs more statistical and methodological rigor, needs to be more ecologically valid, and needs more interdisciplinary integration. The future of social neuroscience, in their eyes, lies both in terms of real-world applications and also in terms of an additional level of sophistication afforded by computational approaches to brain networks.

Key term

Ecological validity

An approach or measure that is meaningful outside of the laboratory context.

Figure 1.3 What do social neuroscientists say about their discipline? Stanley and Adolphs (2013) asked rese...