- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

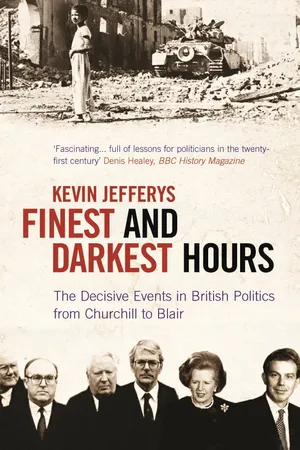

Finest and Darkest Hours

About this book

Kevin Jeffery's authoritative and entertaining book is about the twelve key events in British politics since the Second World War, how they influenced the years that followed them and what Britain might have been like had they not occurred. Combining vivid character portraits with subtle, often highly revisionist, analysis of the unfolding crises, Finest and Darkest Hours ranges from Winston Churchill's accession to the premiership in 1940 through to the emergence of New Labour in 1994, and identifies precisely how significant these episodes really were.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Finest and Darkest Hours by Kevin Jefferys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘In the name of God, go’ Chamberlain, Churchill and Britain’s ‘finest hour’, 1940

One thing is certain – [Hitler] missed the bus.

Neville Chamberlain, speech at Central Hall, Westminster, 4 April 1940

[Winston Churchill] mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.

American broadcaster Ed Murrow, on Churchill in 1940

In the summer of 1940 Britain faced its gravest crisis since Napoleon massed his armies across the Channel nearly one hundred and fifty years earlier. The outline of the story is familiar enough and deeply embedded in popular consciousness as the nation’s ‘finest hour’. On the day in May 1940 when Winston Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister there was an intensification of the war in Europe: Hitler launched his blitzkrieg attack on Holland and Belgium. After the collapse of the French army in June, Britain was left to stand alone against the might of Nazi Germany and, with the prospect of invasion imminent, Churchill played an inspired role in stirring the British people to resist. During July and August the RAF denied Goering’s Luftwaffe aerial supremacy in the Battle of Britain, and by the autumn Churchill was confident that Britain had survived its sternest test. Although the civilian population faced untold new horrors in the Blitz, the prospect of invasion had receded for good, as it turned out – and the government could begin considering ways of striking back at the enemy. Victory in the war remained a long way off, and was to be dependent in the long run on American and Russian military might, but Britain had come through its moment of supreme danger. Inevitably, the coalition government formed by Churchill in May 1940 – the only occasion in the twentieth century when the Conservatives and Labour worked together in office – devoted its entire energies to the war effort. ‘The situation which faced the members of the new Government,’ as the historian Alan Bullock has noted, ‘left them no time to think about the future: they needed all their resolution to believe there was going to be a future at all.”1

In spite of the extraordinary circumstances of the day, it would be wrong to assume that British politics went entirely into abeyance during the summer of 1940. May 1940 witnessed one of the rare occasions when a British Prime Minister was forced from office, and the impact of Chamberlain’s departure was to reverberate for years to come, not only providing the opportunity for Churchill to establish himself as the nation’s great war hero but also undermining the pre-war domination of the Conservative Party and marking a vital breakthrough for Labour – one that was to culminate in a famous election victory in 1945. None of these consequences, however, was inevitable or easy to predict when Chamberlain left Downing Street. It was only much later – and with twenty-twenty hindsight – that the significance of 1940 could begin to be appreciated.

The difficulties of assessing Britain’s ‘finest hour’ are compounded by the need to come to terms with the Churchill legend. For many years after 1945 any criticism of Britain’s saviour was regarded as almost treasonable. The familiar newsreel images of a defiant Churchill with his trademark hat and cigar, the great man’s own influential history of the period (crucially one of the first to appear after the war), and the flattering tone of Martin Gilbert’s multi-volume official biography all painted the same picture of an indomitable figure who came to power as the ‘man of destiny’ and whose bulldog spirit of resistance saved Britain in the nick of time. Only in the last decade, as memories of the war recede, have revisionists put their heads above the parapet. In his book 1940: Myth and Reality, Clive Ponting snipes at Churchill’s personality – talking of his thirst for money and alcohol, among other things – and argues that the untold story of the ‘finest hour’ was one of disarray among British forces and incompetence ‘in relieving the suffering caused by bombing’. For John Charmley, the price of survival in 1940 was post-war subordination to American interests and the demise of the British Empire. ‘Churchill’s leadership was inspiring,’ he writes, ‘but at the end it was barren, it led nowhere.’2

What follows is an attempt to disentangle the reality from the myths of British politics in the early summer of 1940. As the leader who fell from power, Neville Chamberlain has often been presented unkindly; he was, according to one writer, ‘an anachronism, an exhausted old man whose day had passed’.3 It will be argued in this chapter that there was nothing preordained about Chamberlain’s fall from power in May and that, with slightly different handling, he might well have survived to fight another day – with all the consequences this might have had for Britain’s war effort. Churchill, it will be suggested, came out on top not because he was ‘walking with destiny’ – the phrase he used in his own later account – but because he proved most adept and ruthless in exploiting a sudden crisis. The second part of the chapter assesses the new Prime Minister’s early weeks in office and again suggests that the reality was more complex than popular mythology allows. It will be shown that in these early days Churchill was by no means a universally acclaimed war leader and that his authority was only built up gradually through good fortune, as well as through immense resolution. None of this is intended to diminish the scale of Churchill’s achievement. Rather it is to bring him into sharper focus, avoiding the simple verities of his admirers and detractors alike – making him, in the words of the historian David Reynolds, ‘a more human and thereby a more impressive figure than the two-dimensional bulldog of national mythology. Churchill’s greatness is that of a man, not an icon.’4

In tracing how Churchill’s premiership came about, we need to begin by recognizing that – in spite of the newsreel images of an elderly figure with a top hat and umbrella – Neville Chamberlain was one of the most dominant Prime Ministers in modern British history. His authority stemmed in part from the circumstances he inherited from his predecessor, Stanley Baldwin, in May 1937. The Conservative-dominated National government, in power since 1931, had been re-elected in 1935 with an enormous majority of over 200 parliamentary seats – well in excess of the later landslide victories of premiers such as Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair. Equally important to Chamberlain’s dominance was his personal political style. His considerable following among Tory loyalists, from the Cabinet through to rank-and-file activists, was due both to his widely acclaimed administrative ability, displayed in various high offices of state since the early 1920s, and to his determination to lead from the front. Chamberlain dictated policy in a manner alien to Baldwin’s more diffident approach to leadership. He delighted middle-class supporters with his adherence to free-market principles which delivered, after the hardships of the early 1930s, an expanding economy characterized by low taxation and growing home ownership. The regard of Conservatives for their leader was further enhanced by his tough brand of partisan politics. He had no hesitation in scoring points off the Labour Party – only some 150-strong in Parliament – whose leader, Clement Attlee, was widely regarded as an ineffectual, stop-gap figure. Chamberlain never suffered fools gladly and his greatest contempt was reserved for those Labour MPs – ‘dirt’ as he once called them – who felt that they alone could speak for Britain’s industrial heartlands, for the millions of working-class families who had gained little from economic recovery and whose lives continued to be characterized by poverty, poor health, abject housing and high rates of unemployment.

Chamberlain imposed himself on foreign as much as on domestic policy. His strategy towards the European dictators has been the subject of intense scrutiny and controversy among historians; here the intention is simply to make the case that the origins of his downfall should not be sought in the pursuit of appeasement before 1939. The idea of combining increased rearmament with a search for general European peace, although shaped by Chamberlain and his senior colleagues such as Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, met with widespread approval in Conservative ranks. In spite of the controversy about the Munich settlement of September 1938, which conceded Hitler’s demands over the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, no local party associations registered any public protest; indeed, several constituency parties were still expressing their approval of appeasement in the summer of 1939. There were, naturally enough, doubters in the Tory ranks. Prominent among the critics was Anthony Eden, one of the young aspirants for the future party leadership, who resigned as Foreign Secretary in early 1938, ostensibly over differences with Chamberlain about how far to conciliate Mussolini. The small band of Tory MPs whose private deliberations earned them the name the ‘Eden group’ (or ‘glamour boys’, on account of their generally wealthy backgrounds) had growing doubts about the wisdom of Chamberlain’s policy. But open rebellion was never seriously considered. Conservative Central Office, tacitly backed by the Prime Minister, encouraged local associations to put pressure on Tory critics to come into line or else face the possibility of deselection. The Eden group, as a result, offered no concerted opposition to the government either before or after Munich. Eden himself, half promised a return to office, remained non-committal in his public statements, and his refusal to adopt an ‘I told you so’ approach after Hitler’s takeover of the remainder of Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939 removed any doubt about his desire for a recall.5

Eden’s motives were also apparent in his dealings with the Prime Minister’s leading Tory adversary – Winston Churchill. Excluded by successive leaders of the National government in the 1930s, Churchill’s concern about Chamberlain’s strategy became increasingly vociferous during and after Munich. The prospect of Churchill being invited to join the government was so remote that he was less constrained in his views than many of the younger critics, though he, too, faced considerable pressure from his Epping constituency to toe the party line. Throughout this period, Eden’s followers were determined that Churchill and his few associates should not be brought into their discussions. The coolness between Eden and Churchill was partly personal. Before the outbreak of war they had remained equals and rivals; the idea of Eden as Churchill’s protégé and successor emerged only after 1940. For the Eden group as a whole there was a wider consideration: association with Churchill was certain to bring with it charges of disloyalty. Churchill had made so many enemies that he was seen in the party as an isolated demagogue: a figure whose poor judgement was demonstrated by the Gallipoli disaster in the First World War; a maverick motivated by personal ambition and bitterness at his exclusion from office. Divisions between the Tory critics clearly made the Prime Minister’s task easier. Although Churchill began to attract a measure of press support after Munich, Chamberlain had as yet no reason to feel unduly threatened.

The Prime Minister remained firmly in control in the pre-war period. Hitler’s entry into Prague dented Chamberlain’s popularity and led to growing demands from all quarters for the reshaping of the government. Even so, British guarantees to protect Poland in the event of attack helped to contain the critics. The Eden and Churchill groups remained reluctant to co-operate either with each other or with the Labour opposition, which had reversed its neo-pacifism of the early 1930s to demand a tough stand against the dictators. Nor was there much evidence that public opinion had turned decisively against the Prime Minister. The success of an anti-appeasement candidate at the Bridgwater by-election in late 1938 was countered when a Tory critic, the Duchess of Atholl, was defeated after resigning her seat to fight in opposition to Chamberlain’s foreign policy. Though public opinion had become increasingly polarized, the best Labour could hope for in the general election scheduled for 1940 was modest inroads into the National government majority. In addition, the Prime Minister’s tight and unprecedented control of the lobby system ensured that he continued to receive a favourable press from most national newspapers. In the summer of 1939, with the prospect of war impending, there was no question that if and when hostilities began Neville Chamberlain would be the man at the helm.6

It is true that the Prime Minister caused alarm in the Commons by his slow response to Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1 September. MPs gathered at Westminster in anticipation of an immediate declaration of war. But Chamberlain held back, primarily because of difficulties in co-ordinating an Anglo-French ultimatum. The Tory MP for Birmingham Sparkwood, Leo Amery, a fervent imperialist, could not resist an interjection calling on Arthur Greenwood, replying for Labour in the absence of Attlee, to ‘speak for England’. By the time Chamberlain made his famous radio broadcast declaring war on the morning of 3 September, many backbenchers were already asking questions about his suitability for the struggle ahead. Yet he showed great resilience in reasserting his authority, and indeed the recovery of Chamberlain’s prestige was a striking feature of the early weeks of the so-called ‘phoney war’. His handling of erstwhile opponents was crucial in this context. The composition and size of his War Cabinet, at nine strong, gave the Prime Minister scope to control the most important addition to his re-formed administration, Churchill, who became First Lord of the Admiralty. While Churchill was euphoric at this sudden change of fortune, the same could not be said for Eden, who reluctantly accepted a post outside the War Cabinet as Dominions Secretary. These appointments not only silenced the potentially most dangerous sources of party opposition but also left effective power in the hands of Chamberlain and his coterie of senior advisers. The Prime Minister could confidently exclude other leading critics. When the idea was raised of including the likes of Leo Amery, a former Colonial Secretary, Chamberlain dismissed it ‘with an irritated snort’.7 In all, more than two-thirds of ministers from the peacetime government kept their places.

In the early weeks of the war, the Prime Minister continued to look unassailable. The nature of the phoney war also eased pressures on the government. After the defeat of Poland, there were few signs of British forces becoming involved in large-scale military engagements; indeed, it was still widely assumed that Hitler was incapable of waging a long war and that the French army would prevent any further Nazi advance on the Continent. Measures affecting the civilian population, such as evacuation and the blackout, did provoke some disquiet, especially as the reduced level of government activity left backbenchers with more time free to criticize in the House. But Chamberlain was well placed to contain his opponents. Labour had rejected a half-hearted offer to join a coalition and struggled to maintain a policy of ‘patriotic opposition’ – it supported the war but found itself charged with disloyalty if it exercised its right to criticize. Political opponents of the war, such as the British Fascist Party, remained small in number. And, with the exception of the ageing Lloyd George – the Liberal hero of the Great War, whose attitude contained a strong element of personal bitterness against his long-standing antagonist, Chamberlain – those who pessimistically believed that the war could not be won found little publicity for their views in the press. The majority of proprietors decided that, in spite of misplaced trust in appeasement, it was their patriotic duty to continue supporting the government. Opinion polls in November showed that Chamberlain had reached a new peak in public popularity.8

But if the Prime Minister was in a commanding position in late 1939, over the next few months an ebbing of confidence was to take place among even his own supporters; it was a process so imperceptible that government whips were caught completely off guard by the strength of feeling that surfaced in May 1940. In so far as this movement of opinion derived from perceived failures in policy, the major area of concern was the war economy. The Chamberlain government recognized the need to maximize war production on the home front in a manner consistent with providing adequate manpower for the armed forces. To this end, output targets were set in key industries and plans were introduced to raise an army of fifty-five divisions, some of which were soon dispatched to France. For its critics, the government remained too committed to pre-war orthodoxies. Relations with the trade union movement had always been poor and showed only partial improvement, and Labour MPs were able to make a series of telling attacks, especially as unemployment remained at over one million in April 1940. The idea of appointing a powerful Minister for Economic Co-ordination found support well beyond the ranks of the opposition – among sections of the press and from influential figures such as the Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes. But the Prime Minister remained unmoved. When the suggestion was proposed in the Commons in February 1940 Chamberlain refused to take the idea seriously, candidly admitting that such an appointment would undermine his own authority and that of the Treasury.9

These criticisms were not in themselves directly responsible for the fall of Chamberlain. Similar complaints were to persist at least until ‘the turn of the tide’ in the war effort in late 1942. For many at Westminster, bemoaning production levels represented the best of the limited opportunities available to bolster the war effort. What mattered, as the demand for an economic overlord demonstrated, was the inflexibility of the Prime Minister’s response. Chamberlain in wartime had become increasingly intolerant, dismissing the ‘opposition riff-raff’, and confident that his own party’s support would remain solid. ‘The House of Commons,’ Churchill’s friend Brendan Bracken lamented, ‘was no good, the Tory Party were tame yes-men of Chamberlain. 170 had their election expenses paid by Tory Central Office and 100 hoped for jobs.’10 But by the spring of 1940 Chamberlain’s refusal to yield any ground was causing a hardening of feeling. Under the guidance of Leo Amery, the Eden group moved to a more overtly hostile position. More importantly, discontent was spreading. Under the chairmanship of the Liberal MP Clement Davies, an All-Party Parliamentary Action Group committed to a more vigorous prosecution of the war claimed some sixty backbench supporters, and was in touch with both Labour leaders and Tory dissidents. In April the senior Conservative peer Lord Salisbury formed what became known as the ‘Watching Committee’. Salisbury’s initial purpose was to employ private persuasion in moving ministers to greater urgency, in preference to damaging public dissension. But the committee soon found Chamberlain immune to its constructive criticism; within weeks, Salisbury’s group was also becoming more openly critical.11

By April 1940 the Prime Minister was faced with considerable, if still hidden, parliamentary opposition. As Hitler’s forces ended the phoney war with an attack on Scandinavia, British troops became involved in a hastily conceived and ultimately unsuccessful effort to de...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Kevin Jefferys

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 ‘In the name of God, go’ Chamberlain, Churchill and Britain’s ‘finest hour’, 1940

- 2 ‘The turn of the tide’ El Alamein and Beveridge, 1942–3

- 3 ‘The end is Nye’ The demise of Attlee’s government, 1951

- 4 ‘The best Prime Minister we have’ Eden and the Suez crisis, 1956

- 5 ‘Sexual intercourse began in 1963’ The Profumo affair

- 6 ‘They think it’s all over’ The July crisis, 1966

- 7 ‘Who governs?’ The three-day week, 1974

- 8 ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ The winter of discontent, 1979

- 9 ‘Rejoice, Rejoice’ The Falklands war, 1982

- 10 ‘I fight on, I fight to win’ Margaret Thatcher’s downfall, 1990

- 11 ‘. . . an extremely difficult and turbulent day’ Black Wednesday, 1992

- 12 ‘The people have lost a friend’ The emergence of New Labour, 1994

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Index

- Illustrations